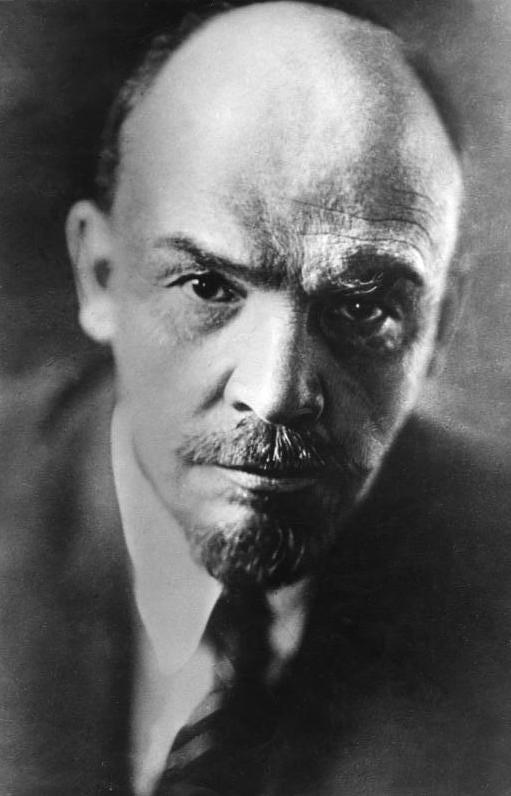

Lenin in July 1920. Photo by Pavel Zhukov.

By 1895, Lenin had been exiled to Siberia for a year but was afforded enough freedom to continue his research and writing on revolution and even communication with other revolutionaries. Upon his release, he visited Europe where he made many significant contacts but most importantly, he met G.V. Plekhanov (Krausz 2015).

Plekhanov was a former Populist who became one of the most well-known Marxists in Russia. He made considerable headway in getting Marxist socialism accepted as a meaningful alternative to Populism. He advocated land redistribution and opposed the tactics of Narodnaya Volya, arguing that terrorism served as a pointless catalyst toward increased government repression (Billington 1970).

Instead of issuing invectives at his philosophical opponents in the revolutionary movement, as was the common practice of the time, Plekhanov relied on the art of persuasion. He acknowledged the Populists’ desire to mix with the masses and work on behalf of their hoped-for political awakening, while explaining the practical shortcomings of this approach.

As a Marxist, Plekhanov was a strict materialist who believed in the possibility of “absolute objectivity.” This undeniable objectivity would supposedly resolve the perennial tendency within the revolutionary movement toward splintering. Furthermore, unlike many other theorists, by 1884 Plekhanov was arguing that Russia was already in a condition of capitalism, albeit in the form of state capitalism. He saw this as evidence of the inevitability of a revolutionary clash between the social classes within Russia and the eventual triumph of the proletariat (Billington 1970).

By this time, Plekhanov saw the peasant commune, held up as proof of a socialist legacy in Russia and a foundation for socialist revolution by the Populists, as falling apart. As it turns out, Russia was not so unique that it could bypass the industrial capitalist stage on its road to socialist revolution. He saw an emerging bourgeois class as playing a major role in revolution and advocated fighting alongside the liberal bourgeois and opposing them after the revolution, if necessary (Deutsch 1964).

Plekhanov would go on to have a complicated relationship with Lenin, whom he saw as a protégé and one who could ultimately execute his ideas (Deutscher 1964). It was later generally recognized that Lenin’s overarching talent was indeed his ability to marry revolutionary political theory and practice.

To be continued

References:

- Krausz, Tamas. Reconstructing Lenin: An Intellectual Biography. Monthly Review Press. New York, NY. 2015.

- Billington, James. The Icon and the Axe: An Interpretive History of Russian Culture. Vintage Books. New York, NY. 1970.

- “The Mensheviks: George Plekhanov” by Isaac Deutscher. The Listener. 4/30/1964.