Levada Center (machine translation), 3/5/25

Denis Volkov in a comment for Forbes about the hopes of Russian public opinion regarding the completion of the special operation.

The majority of Russian citizens are in favor of starting peace talks. 70% of respondents believe that it is necessary to negotiate, first of all, with the United States, hence the optimism associated with the first steps of the new administration. At the same time, half of the respondents still admit that it will not be possible to agree on a peace agreement without the participation of Ukraine.

Russian society is increasingly seized by the hope that the “special operation” in Ukraine may end this year. Such sentiments were manifested in the discussion of expectations for the future, ideas about the possible duration of the conflict, increased attention to the American presidential election, where all eyes were on Donald Trump, who promised to end the Russian-Ukrainian conflict in 24 hours after taking office. And although there was no quick solution, the mood of the American president made an increasing number of Russians believe that a peaceful settlement between Russia and Ukraine is possible.

Request for Discharge

The sheer number of publications about Trump and his remarks in the official Russian media (at times it seemed as if Trump had won the election in Russia rather than in the United States) suggested that Russian elites sympathized with the president-elect and did not rule out a deal with him, which is why the ground is being prepared for a positive public perception of future negotiations. One way or another, by the end of the third year of the conflict, all conversations in Russia revolve around the idea of its possible end – against the backdrop of increased interest in what is happening in Ukraine and attention to the words of the US president.

Focus group participants throughout the second half of last year insisted that “Trump is a businessman” and “you can negotiate with him” – unlike Biden, who, due to his age, seemed to most Russians to be an independent figure, subject to the influence of anti-Russian American elites. Therefore, the appearance of a bright, energetic president in the White House gave at least some hope for the end of the conflict. As respondents said: “Trump promised to end the war, so we are waiting for Trump.”

Is it any wonder that the overwhelming majority of Russians (85%) reacted positively to the Russian-American talks, which started in Riyadh and continued in Istanbul. Moreover, throughout the three years of the conflict, more than half of Russians continued to advocate for improving relations with the United States and the West. Despite the prevailing opposition to America and Europe, most wanted a de-escalation of international tensions, especially amid increasing talk of the possible use of nuclear weapons. At the same time, the prevailing idea was that Russia wanted to negotiate, and the West did not. And now Trump’s election has created a sense that the West’s position may finally change.

It should be noted that, despite the desire for détente and the sympathy of Russians for Trump, the ideal form of relations between Russia and the United States is not seen by the majority as friendship between the two countries – over the past 30 years, significant mistrust has accumulated in Russian-American relations, which is difficult to overcome – but as non-interference in each other’s affairs. People in focus groups have repeatedly expressed the view that it would be good if, after the deal is concluded, Trump “backed off” and “would take care of his own problems,” so that “America would not interfere with us,” and “would stop interfering in our affairs.” But first, a deal must be made.

The majority are in favor of negotiations

Overall, the idea of ending the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and moving to peace talks is currently supported by about 60% of Russians. Similar figures began to appear in polls in the second half of 2024, although after the Ukrainian army’s attack on the Kursk region, the number of supporters of negotiations decreased for some time. Throughout the conflict, the share of those in favor of a peaceful settlement almost never fell below half of the population, and in recent months their number has begun to grow. At the same time, support for negotiations should be perceived as the most general desire to end the conflict and stop the bloodshed. The most frequently heard argument in favor of this – in focus groups and in responses to an open-ended question – is the words that “people must stop dying” and that too many have already died on both sides.

Behind these words there is also hidden anxiety among people that the continuation of military actions could lead to an expansion of the conflict. This, in turn, could mean a new mobilization, which most would very much like to avoid. Therefore, the sooner peace comes, the lower the risks for every Russian family. The growing number of supporters of negotiations is caused not only by general fatigue from the conflict, but also by the changed rhetoric of the Russian authorities, who have been constantly signaling Russia’s readiness for negotiations in recent months. And such talk influences public opinion, preparing it for a possible settlement of the conflict.

It is worth adding that it is categorically wrong to oppose the supporters of negotiations and supporters of the authorities, as some researchers and publicists do. Polls show that support for negotiations prevails even among loyalists and for all three years it was they who made up the majority of supporters of the end of hostilities. Another thing is that they believe that it is the country’s leadership that should determine when and under what conditions to conclude a peace agreement. “It would be good if the conflict ended as soon as possible,” but “we are small people, let the big people decide,” “Putin has all the information, he knows better,” they say in focus groups.

Less than a third of Russians oppose negotiations and support the continuation of hostilities over the past couple of months, despite the fact that on average throughout the conflict there were about 40% of the population. Their main argument is that “you can’t stop halfway”, “you need to finish what you started”, because “so much has already been sacrificed”. It should be emphasized that loyalists also prevail in this group. The positions of those who criticized the authorities “from the right”, demanding more decisive action (Igor Strelkov became a symbol of this position), have always been marginal on the scale of the entire society and hardly exceeded 5-6% of the total population.

Interestingly, some Russian liberals who do not accept negotiations until Ukraine wins are also in the camp of opponents of a peaceful settlement today – the most prominent exponents of these ideas are the organizers of opposition rallies in Berlin. In society, their share is about the same 5-6%. Such unity between liberals and the far right should not be surprising: a similar situation was already observed in 2023, during the days of Prigozhin’s rebellion, when some supported Yevgeny Prigozhin himself, while others simply wanted the defeat of the regime. Be that as it may, both of these positions remain marginal.

Negotiations – with whom?

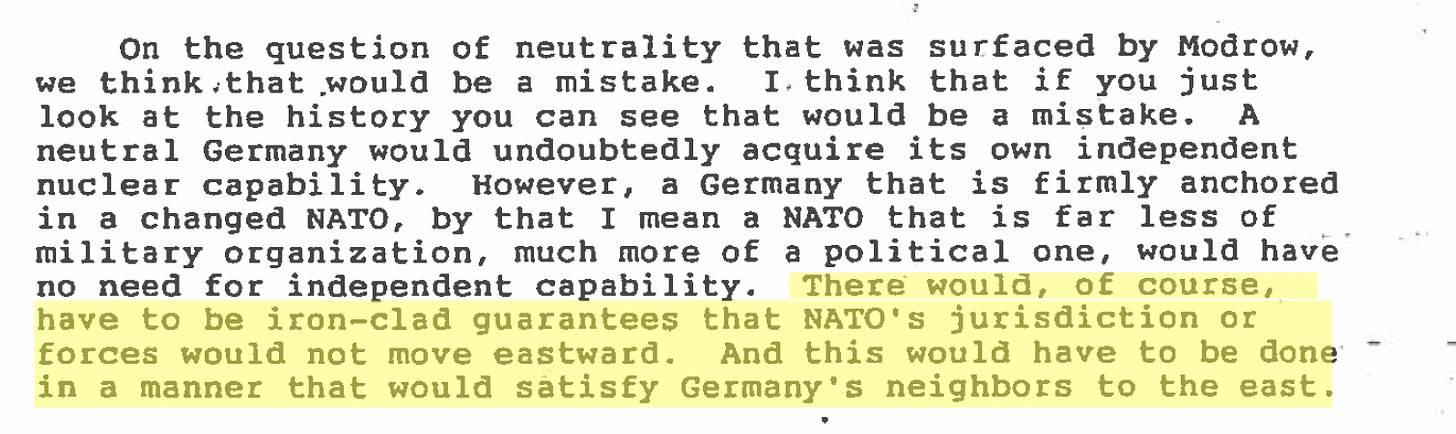

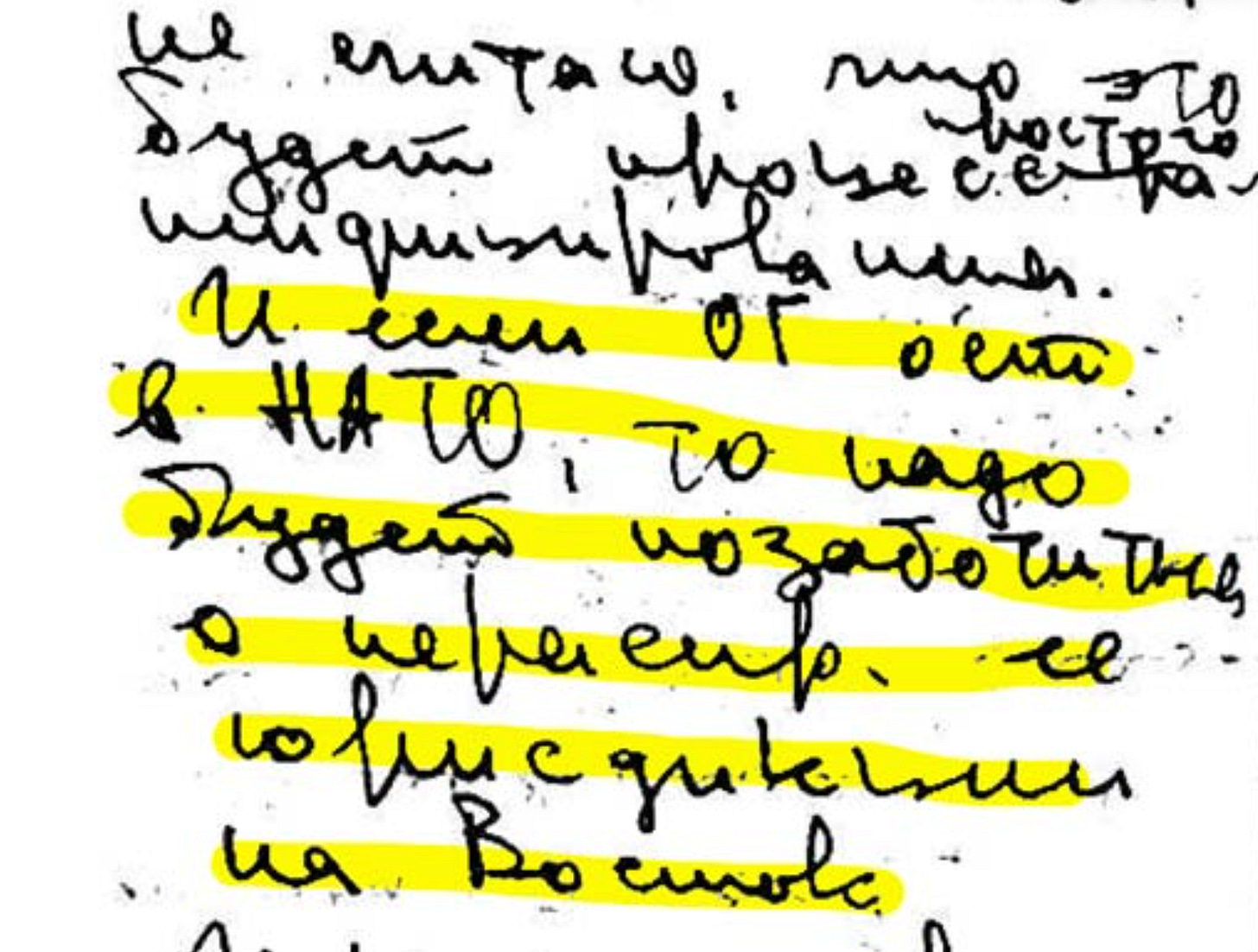

Let us return, however, to the desire for peace negotiations prevailing in society. According to the majority (70%), such negotiations should be conducted primarily with America – we have repeatedly said that the majority of the Russian population perceives the current conflict as a confrontation between Russia and the West under the leadership of the United States, in which Ukraine plays only a subordinate role. Such perceptions of what is happening prevailed in Russian society even before the outbreak of hostilities against the backdrop of the escalation at the end of 2021. Since then, these views have only strengthened.

Only half of the respondents consider it expedient to negotiate with Ukraine, and only a quarter consider it expedient to invite Europe to the table. With all the perception of Ukraine as subordinate to the West, there is an understanding that the signing of a peace agreement cannot do without its participation. At the same time, there is a strong feeling in society that Ukraine does not want to negotiate and therefore it is useless to negotiate with it now.

The perception of Europe’s role during the conflict gradually changed. If at the very beginning the EU countries were perceived as completely dependent on the United States, acting under its dictation, then over the past year and a half, the share of those who saw European leaders, such as French President Emmanuel Macron or the head of the European Commission, Ursula von der Leyen, with their own position on the Ukrainian conflict, even tougher towards Russia, has been gradually growing in Russian public opinion. than the United States.

The negotiations that began between the Russian and American delegations and the apparent divergence of the public positions of the United States and Europe regarding the scenarios for ending the conflict finally consolidated this idea. It got to the point that the attitude of Russians to the United States today for the first time turned out to be better than to the European Union – 30% against 21% in February 2025. It is very interesting how sustainable this new trend will be.

From a position of strength

Although support for a peaceful settlement prevails in society, the majority has no desire to make peace at any cost. Thus, with a gradual increase in the number of supporters of negotiations, the number of people who are ready to do this at the expense of the return of new territories is decreasing. Most likely, this dynamics is explained by the fact that three-quarters of respondents today are confident that Russia is winning on the battlefield. About the same number – 72% – believe that military operations are going well for Russia, although the occupation of part of the Kursk region and regular raids by Ukrainian drones inspire some concern. And this is the highest figure since the spring of 2022, until the retreat of the Russian army from Kherson and the Kharkiv region. And since Russia is gradually gaining the upper hand, negotiations can be conducted from a position of strength.

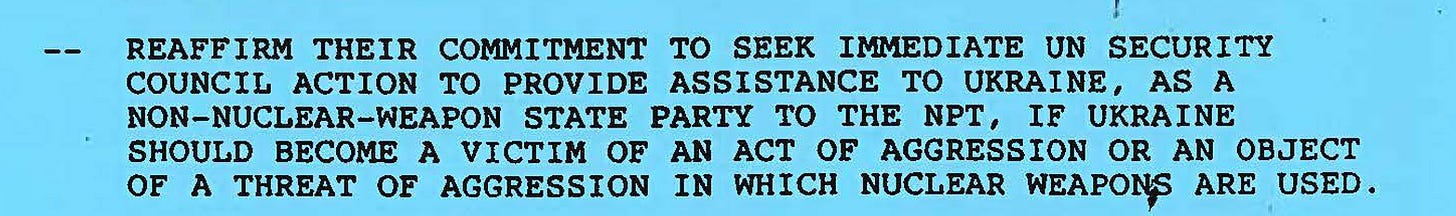

And while the number of people willing to make concessions for a peace deal has risen slightly over the past six months, from 20 percent to 30 percent, much of this remains just a declaration, because Russian public opinion is becoming increasingly intractable on major issues that will require an agreement with Ukraine. Thus, the number of people who are ready to admit the idea of Ukraine’s membership in NATO or the return of the DPR and LPR or the Zaporozhye and Kherson regions to Ukraine is systematically decreasing. Today, between 70% and 80% of Russians, depending on the question, consider such conditions unacceptable for Russia.

Also, if we take out of brackets the idea of the exchange of prisoners of war, which is supported by both sides (in Russia, it is 92% of respondents), the most popular conditions for concluding a peace agreement in Russian society are unlikely to find understanding from the Ukrainian side. Thus, the absolute majority of Russians – more than 80% – would like to guarantee the rights of the Russian-speaking population and protect the status of the Russian Orthodox Church in Ukraine. It was the protection of compatriots that our respondents saw as the main goal of the “special operation” over the past three years.

Moreover, about 70% of Russians would like to establish a friendly government in Ukraine, ensure the neutral status of Ukraine, and lift Western sanctions. However, on the latter question, even a large proportion of Russians (77% in February 2025) believe that Russia should continue its policy despite the sanctions: if they cancel it, it’s good, if they don’t, that’s fine.

Such sentiments coincide with the statements of the Russian authorities, but completely contradict the position of the Ukrainian leadership. And if there are no grounds for a compromise between the parties to the conflict, the wait for the much-desired end of the bloodshed may drag on.

Like this:

Like Loading...