By Dmitry Trenin, RT.com, 1/19/23

Dmitry Trenin is a research professor at the Higher School of Economics and a lead research fellow at the Institute of World Economy and International Relations. He is also a member of the Russian International Affairs Council.

Predicting the course of political events during particularly volatile periods, such as the one we entered a year ago, is a thankless and meaningless endeavor. Yet in such times, there’s both a need and an opportunity to gain a deeper understanding of the main trends shaping the world. This brief overview is an attempt to identify Russia’s main course of development in the international arena and its relations with key players in the year ahead.

Ukraine

The longer the conflict in Ukraine lasts, the more it resembles an uncompromising confrontation between Russia and US-centric Western countries. The escalation of hostilities continues to be the dominant trend. The stakes are extremely high for all sides, but for Moscow even more so than for the United States or Western Europe. For Russia, the conflict is not only a matter of external security and its place in the world, but also a matter of internal stability, including the cohesion of its political regime and the future of Russian statehood. After the partial mobilization last fall, combat operations in Ukraine began to resemble something far broader. What started out as a “special military operation” may well become a “patriotic war.”

All conflicts eventually come to an end as a result of agreements. However, the above circumstances make it nearly impossible to conclude either a peace agreement or even a stable armistice similar to the Korean deal of the 1950s. The problem is that Washington’s maximum concessions are a far cry from Moscow’s minimal goals. The objective of the US is to exclude Russia from among the great world powers, initiate regime change in Moscow, and deprive China of an important strategic partner. Its strategy is to exhaust the Russian Army at the battlefront, shake up society, undermine people’s trust in the authorities, and finally, get the Kremlin to surrender. As for Russia, it has the resources and power to get the better of these schemes and achieve its goals in such a way as to avoid another armed conflict in the future. In 2023, combat operations in Ukraine may not end, but over the next 12 months, we will see whose willpower is stronger and which side will eventually prevail.

The West

The Ukrainian conflict has so far been a proxy war between Russia and NATO. However, the growing number of Western countries joining the conflict and aiming to “strategically defeat” Russia may lead to a direct clash between the Armed Forces of Russia and Western military units. If this happens, the Ukrainian conflict will turn into a Russia-NATO war. Such a situation will inevitably carry a nuclear risk. This is further aggravated by the fact that, acting out of desperation, Kiev authorities may provoke the US-led military bloc to directly enter the conflict.

However, even if a head-on collision is avoided, the West’s overall hostility towards Russia will keep on growing. Economic relations between Russia and Western Europe, which the latter sabotaged last year despite the evident “suicide” of such actions, will continue deteriorating.

Western European countries are continuing to isolate themselves from Russia, seeing it as a direct threat and using this “menace” to boost the internal cohesion of their own bloc. For over half a century, “European security” has been a safe haven for international diplomacy and a mantra for foreign policy. But now, the Western Europeans have dropped the pen and taken up the sword – or, more precisely, artillery systems.

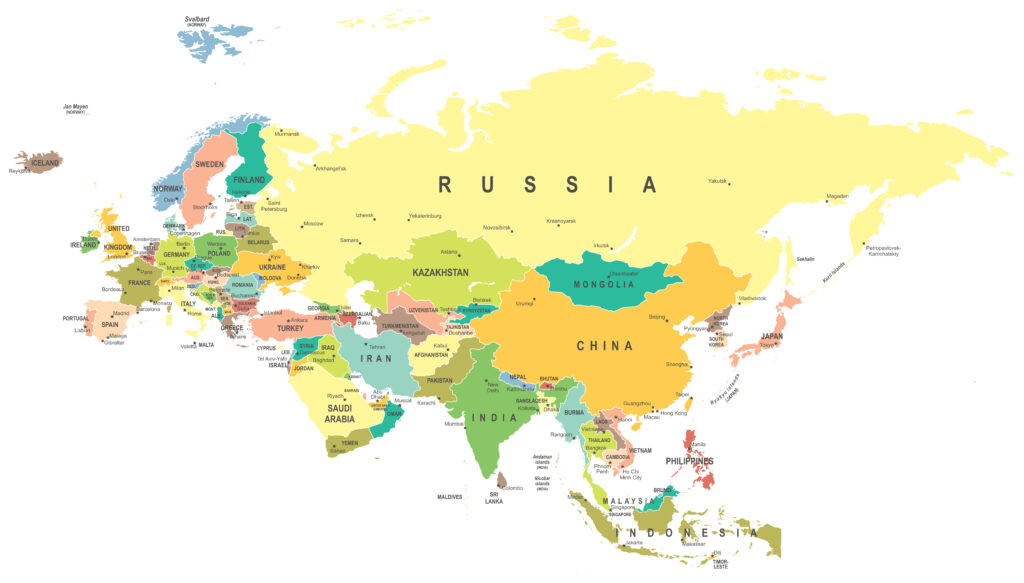

Ukraine is currently the most significant battlefront between Russia and the West, but not the only one. The front of confrontation extends north through Belarus, Kaliningrad, and the Baltic into the Arctic, and south through Moldova, the Black Sea, Transcaucasia, Kazakhstan, and Central Asia. Of particular importance in 2023 are Kazakhstan and Armenia, where the West is actively supporting anti-Russian nationalist powers, and Moldova and Georgia, where it’s attempting to rekindle old conflicts and open a “second front” in addition to the Ukrainian one.

In Russia-US relations, dialogue has long been replaced by a hybrid war. And Ukraine is but one direction, albeit the most noticeable, that this showdown is taking. Washington’s goal is to actively demonstrate its global dominance and it’s willing to take serious and risky steps to this end. Moscow is not the main opponent for Washington, but one that needs to be taken down first. US foreign policy is merciless to rivals, opponents, and allies alike, and Russia can count only on its own power to hold the Americans back.

Ahead of the 2024 presidential elections in the US, political struggles are predictably set to escalate. The Republicans, who recently took control of the House of Representatives, will likely demand greater accountability for the funds allocated to Ukraine. These largesse may also be somewhat reduced. Nevertheless, most Republicans share the views of President Joe Biden’s administration regarding both Ukraine and Russia, so a change in US policy in favor of Moscow remains highly unlikely.

In terms of relations between Japan and Russia, cooperation established by former prime minister Shinzo Abe is being replaced with Cold War-era hostility. In contrast to Western Europe, Japan isn’t willing to break off energy ties with Russia. But the revitalization of the alliance between Japan and the United States, coupled with the strengthening military-political ties between Russia and China and mounting tension on the Korean Peninsula all signal a return to the old confrontation with Russia, China, and North Korea on one side, and the United States, Japan, and South Korea on the other.

The East

In the current circumstances, Belarus remains Russia’s only absolute ally. At the same time, Moscow maintains partner relations with several nations whose importance has grown significantly in recent times. These are primarily the great world powers China and India; regional players Brazil, Iran, Turkey, and South Africa; and the Persian Gulf countries – primarily Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates. These countries, along with dozens of others, have not joined in the Western sanctions against Russia and continue to be Moscow’s partners. However, Asian, African and Latin American countries that exist within Washington’s financial empire, which are increasingly called “the world majority” in Russia, are forced to consider the effect of secondary US sanctions.

This is apparent in the case of China. The proposal of a Russian-Chinese partnership “without borders” demonstrates the willingness of both world powers to develop in-depth cooperation in all fields. Despite Washington’s considerable efforts to use the Ukrainian conflict to sabotage China-Russia relations, economic and military ties between Beijing and Moscow are growing stronger. The promised visit of Chinese leader Xi Jinping to Russia, scheduled for the spring of 2023, is evidence of the ongoing rapprochement.

At the same time, both sides are acting out of their national interests. For Russia, the United States is currently an opponent. But for China, it is only a rival and a potential opponent. This is not enough to form a military alliance between Moscow and Beijing. China naturally values its economic interests in US and European markets, and Beijing may change its mind in favor of a military alliance only if Washington becomes its enemy. For the sake of Russia alone, China is not willing to take this step.

There are also issues around Russia’s relations with India. Just like Beijing, New Delhi is Moscow’s strategic partner. Yet with its ambitious goal of accomplishing a major economic leap in the current decade, India is particularly interested in economic and technological cooperation with the US, the EU, and Japan. Moreover, New Delhi sees Beijing as its main rival and a potential military threat: the smoldering conflict on the border between the two most populated Asian states continues to occasionally flare up. In addition to BRICS and SCO membership, India is a member of the Quad group, which the US views as an anti-Chinese alliance.

In such conditions, Russia will have to decisively strengthen its positions in India in 2023. This includes actively working with local elites, explaining Russia’s foreign policy and countering the attempts to distort it by Western media (used by the Indian press as its main reference), finding and developing new opportunities for economic, technological, and scientific cooperation, and encouraging productive cooperation via international forums and other platforms. In the opposite case, a “go with the flow” attitude in Russian-Indian relations will result in India’s drift away from Moscow.

Last year, Iran became the only country to supply its own weapons systems to Russia. At the same time, Tehran entered the process of joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO). The North-South Transport Corridor linking Russia with the Persian Gulf nations, India, and South Asia has acquired particular importance under Western sanctions. Also, last year it finally became clear that the Iranian nuclear deal would not be extended. This means the suspension and possibly even the termination of over half a century of cooperation between Russia and the United States on nuclear nonproliferation.

In 2023, Russia and Iran will continue growing closer. On the Russian side, this will require the development of a more concise and active strategy towards the Middle Eastern state.

Moscow’s relations with Tehran directly influence its relations with the Arab nations and Ankara. The region is notable for having several centers of power. The policy of the Persian Gulf’s Arab countries (especially Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates) is becoming increasingly multi-vector. They are no longer focused solely on the US and are developing ties with Russia and China. In the coming year, this trend will likely continue and strengthen. Having proposed a concept for regional security in the Gulf zone back in 2019, in 2023 Moscow could step up the efforts and facilitate dialogue between Iran and its southern neighbors.

2023 is the centenary of the proclamation of the Turkish republic, and will see presidential elections. For Russia and its foreign policy, the importance of Turkey has grown dramatically in recent years. As a result of the Syrian war, the Second Karabakh War, the Ukrainian conflict, and the collapse of normal relations between Russia and Western Europe, Turkey turned into a transport, logistics, and gas hub between Russia and the Euro-Atlantic world.

The Turkish opposition is determined to put an end to the 20-plus year political reign of Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who intends to run for another (according to him, final) presidential term. We won’t make predictions concerning the upcoming election but will only point out the trend that Turkey is transforming from a regional power into a major independent player with global ambitions. This makes Ankara an indispensable, if challenging partner for Moscow.

Close neighbors

Last but not least are Russia’s relations with its immediate neighbors. This trend came to the fore in 2022 and is set to continue. Over the coming year, achieving a breakthrough and eventually, victory in Ukraine, will be Russia’s main priority. Belarus will remain Russia’s closest ally and partner. Meanwhile, the rise of ethnic nationalism in Kazakhstan and potential discord in relations between Moscow and Astana pose the greatest risk.

Other threats may include a Moldovan attempt to cooperate with Kiev and the West on solving the Transnistria conflict; a potential renewal of hostilities between Armenia and Azerbaijan; another outbreak of the border dispute between Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan, and internal destabilization issues in neighboring countries.

On the other hand, under the influence of last year’s gigantic geopolitical, strategic, and geo-economic shifts, it has become obvious that we need a fundamentally different level of economic and military-political cooperation within the frameworks of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), respectively. It’s worth noting that in both aspects, Russia-Uzbekistan cooperation looks particularly promising. What is clear is that under the conditions of unprecedented geopolitical tension along the entire perimeter of Russia’s new post-Soviet borders, Moscow will need to invest a lot more attention, understanding, and effort to reap results. This will become one of the key challenges for Russian foreign policy in 2023.

This article was first published by Profile.ru.