Edward Bernays and the Manipulation of the Public Mind

Edward Bernays was the nephew of pioneering Austrian psychiatrist Sigmund Freud. His parents had settled in the U.S. and Bernays grew up American, but came to be deeply influenced by his uncle’s ideas about the unconscious, its role as the repository of repressed sexual and aggressive impulses and its potential use as a means of manipulating the masses. Bernays was also influenced by social psychologist Wilfred Trotter’s theories on crowd psychology and the “herd instinct.”

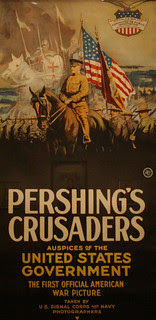

During WWI, which threw Freud into a deep depression because he saw it as confirmation of his worst fears about human behavior, Bernays was working as a press agent and was asked to assist the war effort by participating in the American government’s committee on public information, known as the Creel Committee. His great contribution was effectively promoting

Inspired by the achievements of propaganda during wartime, Bernays, looking to make his fortune, set to work on turning Americans from citizens into passive consumers who would be controlled by channeling their unconscious desires into a constant quest for goods and services that they would associate with their deepest yearnings for beauty, freedom and fulfillment. Bernays would come up with tactics to bombard the public with messages that would cement this objective.

One of his first successes involved helping the tobacco industry expand their market by breaking the taboo against women smoking in public. After soliciting the advice of the top psychoanalyst in America who told him that cigarettes were a phallic symbol and represented male sexual power, he realized that if cigarettes could be associated with challenging men’s power, women would respond positively to smoking as it would be connected to the ideas of freedom and rebellion —two of the most common marketing concepts to this day.

At the annual Easter Day Parade in New York City, Bernays staged a memorable event in which a group of “rich debutantes” lit up cigarettes in theatrical fashion at Bernays’ pre-arranged signal. He had tipped off the media that a group of “suffragettes” would be lighting up what they called “torches of freedom.” As Bernays knew, who could argue against freedom in America? By associating cigarettes with freedom to women, Bernays had helped the tobacco companies hit the jackpot.

Bernays and his insights soon became indispensable to corporate America, which was worried that consumer demand for their products would plateau as mass production had been mastered and people at the time tended to buy goods based on need and durability. Only a small group of wealthy people could buy a significant number of luxury items. Consequently, to continue growing their markets, they needed to “transform the way the majority of Americans thought about products” as Paul Mazen, a Leahman Brothers Wall Street banker said. Mazen turned to Bernays for implementation of this transformation.

As Peter Solomon, investment banker for Leahman Brothers, said about Bernays in the documentary film Century of the Self:

Prior to that time there was no American consumer, there was the American worker. And there was the American owner. And they manufactured and they saved and they ate what they had to and the people shopped for what they needed. And while the very rich may have bought things they didn’t need, most people did not. And Mazen envisioned a break with that where you would have things that you didn’t actually need, but you wanted as opposed to needed.

As the New York banks financed the spread of chain department stores across the country to serve as oases of consumerism, Bernays came up with many methods of product promotion that would become pervasive later on, such as linking products with movie stars who were also his clients, adorning those same movie stars in clothes and accessories made by other corporate clients during public events, and prominently placing products in films.

He also paid psychologists to issue reports claiming that certain products and services were good for people’s well-being and celebrities to push the idea that clothes were not merely necessities but a means of self-expression. This became known as the “third party technique” of conferring legitimacy by what appears to be a disinterested party or an authoritative source.

The dramatic growth in consumerism that Bernays actively facilitated contributed to the stock market boom. After it crashed in 1929, however, challenges were presented to the idea that Americans were consumers rather than citizens as the consumer boom could no longer be sustained and Franklin Roosevelt’s administration actively lobbied against it as part of the New Deal program. Supreme Court justice Felix Frankfurter in a letterto Roosevelt described Bernays and his PR colleagues as “professional poisoners of the public mind, exploiters of foolishness, fanaticism, and self-interest.” Unlike Bernays, Roosevelt and his colleagues believed that people could be trusted to make rational decisions if their fears, desires and insecurities were not manipulated in other directions as reflected in Roosevelt’s famous admonition, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself.”

Bernays eventually saw his ideas transferred into the realm of political philosophy as renowned political writer and repentant former socialist Walter Lippmann, who had served with Bernays on the Creel Commission, began to apply Freud’s ideas to a need to control the masses politically, viewing the Russian Revolution as an example of the dark forces of the rabble being unleashed. Bernays was intrigued by Lippmann’s interpretation of his uncle’s ideas — contained in Freud’s books which Bernays professionally promoted in the U.S. Lippmann had begun to openly question the feasibility of democracy:

The lesson is, I think, a fairly clear one. In the absence of institutions and education by which the environment is so successfully reported that the realities of public life stand out sharply against self-centered opinion, the common interests very largely elude public opinion entirely, and can be managed only by a specialized class whose personal interests reach beyond the locality.

In his 1922 book, The Phantom Public, Lippmann stated plainly: “The public must be put in its place [so that we may] live free of the trampling and the roar of a bewildered herd.”

In 1930’s Germany, the Nazis were also asserting that democracy was not feasible and Joseph Goebbels, who emerged as the Nazis’ pre-eminent propagandist, had taken note of Bernays methods of public manipulation based on Freudian theory as a way to channel the desires of the population in a particular direction favored by the leaders. Goebbels reportedly admitted putting Bernays’ book Crystallizing Public Opinion to use in the regime’s genocidal campaign against the Jews in terms of creating a public environment of hatred and scapegoating.

Having honed his propaganda skills since WWI, Bernays would once again provide his services on behalf of the martial ambitions of the U.S. government. He served as an advisor to Eisenhower and believed that the best way to deal with Americans’ fear of Communism and the nuclear arms race was to manipulate those fears to support America’s mobilization in the Cold War.

In 1954, Bernays assisted the CIA’s overthrow of Guatemala’s democratically elected leader, Jacobo Arbenz, a democratic socialist with no ties to the Soviet Union. The CIA had a propaganda program in place called Operation Mockingbird, in which numerous journalists and editors — both paid and unpaid — published and broadcast stories sympathetic to the increasingly aggressive and unaccountable agency. Led by Frank Wisner, Operation Mockingbird was also used to suppress reporting that would expose the agency’s nefarious covert activities or present them in a negative light.

Bernays’ role was to create a narrative that portrayed the coup as the popular overthrow of a Communist dictator and puppet of Moscow whose removal represented the spreading of democracy. In reality, Arbenz’s ouster was to preserve the profits of United Fruit Company, a company that Bernays had worked for in a PR capacity since the 1940’s while the head of the CIA, Allen Dulles, had made investments in United Fruit in his earlier years as a lawyer at the Sullivan and Cromwell firm which served as United Fruit’s corporate counsel.

To continue reading, click here