18 years ago today, Rachel Corrie was run over by an Israeli bulldozer while volunteering with the International Solidarity Movement (ISM) to prevent the destruction of a Palestinian home in Rafah. In June of 2004, I got the opportunity to interview Rachel’s parents, Craig and Cindy Corrie, before a speaking engagement at the local Peace and Justice Center in Walnut Creek, California.

I had been writing for the Peace and Justice Center’s newsletter for about a year or so and had recently branched out from summarizing pre-published material on foreign policy to creating more original content, including interviewing folks who had special knowledge and/or experience about topics we were covering that involved war/peace and international affairs. This was my second major interview and I actually went back and forth in my mind in preparing the questions about whether and how to approach the question about how Rachel had been portrayed in the mainstream American media after her death. On the one hand, I knew it was a legitimate question to ask. On the other hand, it involved a painful personal loss and not just discussion of something in the abstract. My hesitancy about this made Cindy’s answer all the more interesting.

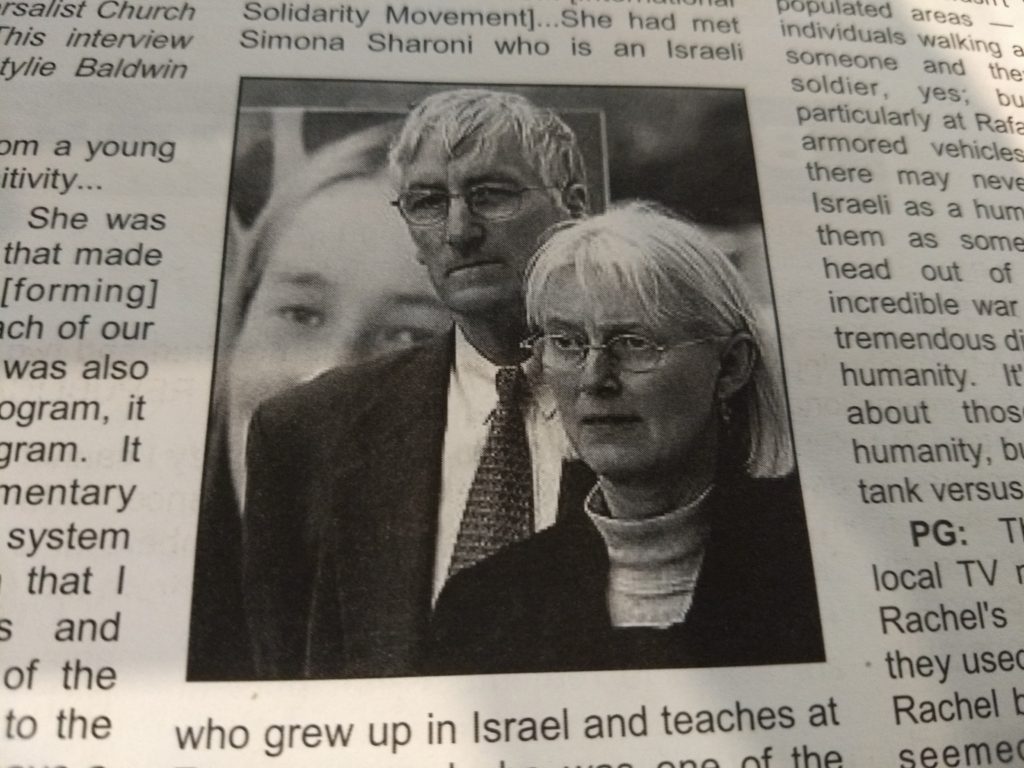

I spoke to both Craig and Cindy, but at one point Craig excused himself to help with the setup for their presentation, so I spoke to Cindy for longer. This was a little over a year since Rachel had been killed and Cindy seemed physically weighed down with the grief. I saw her and Craig a few years later at the performance of a play that had been written about Rachel and adapted from her prolific journal entries from high school through college. She looked much happier and did not have the weighed down look from 2004.

Below is the edited interview. – Natylie

Natylie Baldwin: It sounds like from a young age, Rachel had this sensitivity…

Cindy: Yes, she did. She was our third child and I think that made some difference in [forming] uniquely who she was. Each of our kids is very different. She was also able to be in this school program. It was called the Options Program. It was an alternative elementary program in the public school system in Olympia [Washington state]. It’s a program that I worked with other parents and teachers to begin and part of the emphasis was on connecting to the community and also trying to have a lot of hands-on experiences for children, but also connecting the community to the larger world. So I really feel like that program, during those really young years, did have an impact in making her feel she could have an impact on the real world and that she had some responsibility to find out what was going on in the real world and to ask questions and so forth…

NB: When did Rachel start to become interested in the Israeli-Palestinian issue in particular?

Craig: Rachel’s response to 9/11 was that she wanted to become a peace activist. So, within weeks after that, within the community of Evergreen [state college Rachel attended] and of Olympia, she really melded both of those communities together…she joined a number of peace groups. There were people who had been with ISM. She had met with Simona Sharoni who is an Israeli who grew up in Israel and teaches at Evergreen and she was one of the founders of Women in Black. Simona is a powerful woman and a powerful voice and she had been a teacher to Rachel and some of her friends. So she started to learn about that and as she worked with the peace groups I think she got more and more centered on Israel/Palestine and came to the conclusion that that’s really the linchpin of the strife that the United States centrally finds itself involved in after the Cold War. And I think that she learned about Rafah and realized that that was one of the most forsaken places on the earth, and so it’s really right in the center of the problem…

Craig: [Speaking about the conditions in Gaza]….it’s hard – now I’m a Vietnam veteran and when I was in Vietnam – well, I was out in the jungle, I wasn’t very often in populated areas – but we were individuals walking and you look at someone and they look like a soldier, yes; but down here, particularly at Rafah, they are all in armored vehicles. The children there may never have seen an Israeli as a human being; they see them as somebody sticking their head out of a tank – these incredible war machines. There’s a tremendous difference, I think, in the humanity. It’s kind of awful to talk about those relative levels of humanity, but seeing somebody in a tank [versus a regular vehicle]…

NB: The local newspaper and a local TV news station that covered Rachel’s death had an image that they used. I guess an older image of Rachel burning an American flag. It seemed that people in my community and other communities across the country relying on the mainstream media, got this image of Rachel as angry, unappreciative, America-bashing.

Cindy: I’m so glad you asked me about that because I think some people are refraining from asking me about it. And it’s not that old of an image…On February 15th she was at the Children’s Parliament with the ISM [in Gaza] and they organized this little protest. It was not actually an American flag. It was a paper image where they had drawn with crayon, and they had Israeli flags and American flags. You can’t see it in the photo, but one of Rachel’s friends told me that she had written onto the stripes the names of all the corporations she thought would benefit from a war with Iraq. And the children handed up to her these images of the flags to burn. And I think burning flags is a lot more common there. Anyway, she said she looked at those images and she knew she couldn’t burn anything with the Star of David on it but she thought she could protest by burning the image of her own flag.

She called me because that photo was actually available; it came out that day. Craig and I came home and I think it was on the phone message, “Mom, I just wanted to warn you that there’s a photo I’ve seen out on the wire and it makes me look like a mad woman.” And I don’t know if it was something about the fire or the burning or whatever that just made her look strange and, uh, angry. And that’s not Rachel’s personality. I just wouldn’t describe her as an angry woman; it’s just not at all my image of her, but I can see that she looked that way in that photo…[there] was actually a different image, one where she’s still burning this paper flag, but her eyes are open and her face is kind of lit up with a smile and it conveys something different…

It was such a lesson about the power of photos, and then you always have to wonder about the selection of photos on the part of the media because there are choices…it would just make me feel better if they got the full story behind them, because I think it can really distort a human being and even a situation they were involved in at the time…it was not anti-American or even anti-Israel, for that matter. It was on behalf of these people who are suffering…

A very touching thing happened after she died. Traditionally, people carry the bodies of people who have died through the streets, but we didn’t permit that in Rachel’s case. But they did have mock funerals with a mock coffin for her – one where there was this picture of children with flowers and the coffin is draped in an American flag. I don’t think it was a real American flag, it almost seemed like it was painted on, and people said that that was the first time in years that they could remember seeing the American flag treated in a respectful way.

I don’t think Americans understand how throughout the world we are viewed as being complicit in what is happening with the Palestinian people – and how much anger that creates toward us. And Rachel, I think, showed an image of a different kind of American, who had compassion for what was happening to these people…