By Alexander Dynkin and Thomas Graham, Politico, 2/9/22

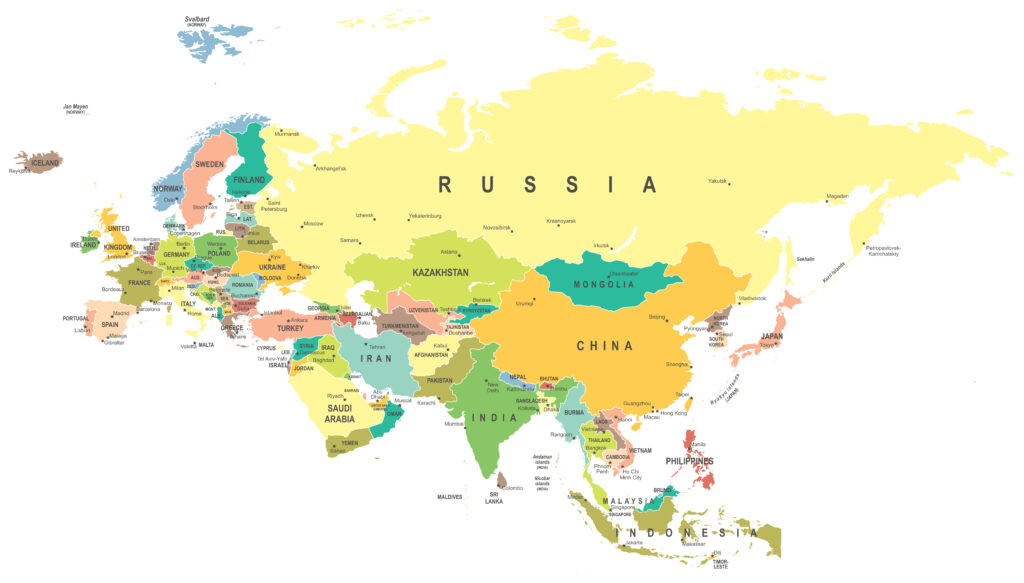

We see four elements to a solution. First, restrictions on military operations along the NATO/Russia border. Second, a moratorium on NATO expansion eastward. Third, resolution of ongoing and frozen conflicts in the former Soviet space and the Balkans. And fourth, modernization of the 1975 Helsinki Accords, which created a pan-European forum and articulated agreed principles of interstate relations to undergird East-West detente.

These four elements must be negotiated as a package, although progress is likely to proceed at different paces along the four tracks, because both the United States and Russia need to see where they are headed before they will engage in substantive talks on details.

Curb military operations. To reintroduce military restraint along the Russia/NATO frontier, the two countries can begin by resurrecting aspects of Cold War agreements that have fallen into abeyance in recent years as one or the other side lost interest in adhering to them. Both sides agree that this is an important step, although Russia insists that it be taken only after the issue of NATO expansion is addressed — one more reason why all aspects of the settlement must be on the table if there is to be progress on any one of them.

Today, the two sides need to reaffirm agreements to avoid dangerous incidents at sea or in the air. They need to negotiate something akin to the Conventional Forces in Europe Treaty that regulated military activities in nonthreatening ways in border areas, taking into account current realities. They need to resurrect the INF Treaty at least for Europe — that is, no deployment of land-based intermediate-range ballistic missiles on the continent. That will require the United States and Russia to resolve grievances that led to the treaty’s demise in 2019, when neither country was prepared to muster the political will to pursue the technical fixes that could answer its concerns. Reaching agreement on these matters will take time, as it did for analogous agreements during the Cold War, but agreement is surely possible.

Agree to a moratorium on NATO expansion. NATO’s expansion eastward is the crux of the current dispute. One of us has proposed a formal moratorium on expansion into former Soviet states, including Ukraine, for 20-25 years. The other proposes 2050 as the year in which the moratorium would end. There is nothing magical about the period; it just needs to be long enough so that Russia can claim its minimal security requirements have been met, and short enough so that the United States can credibly claim it has not abandoned the open-door policy. Even if a moratorium cannot be agreed, it should prove possible to find a mutually acceptable way to make it clear that Ukraine is not going to join NATO for years, if not decades, to come — something American and NATO officials will readily admit in private.

At the same time, the two sides should seek agreement on limits to NATO activities in and around Ukraine that meet Russia’s security concerns, but once again do not compromise NATO’s principles. Those could include a pledge by NATO member states not to build or occupy military bases in Ukraine or to supply Ukraine with offensive weapons systems that could strike Russian territory in exchange for a Russian pledge not to deploy certain weapons systems within a defined zone along Ukraine’s borders. This would not be an extraordinary concession by NATO members. In the 1997 NATO-Russia Founding Act, NATO pledged not to deploy nuclear weapons or substantial permanent combat forces to new member states — because it had no plans to do so in any event. Certainly, NATO can now make pledges to refrain from certain types of activities with regard to nonmembers, if that will help ease Moscow’s concerns.

Resolve “frozen” conflicts. The ongoing and frozen conflicts in the former Soviet space and the Balkans, including Crimea, Kosovo and Donbas, all involve separatism of some sort. All should be resolved on the basis of some form of local democracy, that is, a vote to ascertain the will of the people in the separatist regions is the starting point, after which a series of technical agreements need to be reached to regulate issues that would necessarily grow out of any peaceful secession of a territory from a larger state. The exact form of the vote could be adapted to the specific circumstances of each conflict. It need not be a referendum on the issue of separatism. In the cases of both Crimea and Kosovo, the most prominent conflicts, regularly scheduled elections could serve this purpose, with the stipulation that victory would require that a qualified majority of the electorate vote for candidates who support separatism. The only requirement would be that the vote be internationally observed and then certified as free and fair to erase any doubt that it was legitimate. Such votes would undoubtedly reaffirm what most impartial observers know to be the hard truths that Kosovo will remain independent and Crimea will never go back to Ukraine. A similar vote could be used to determine how to move forward with the Donbas separatist regions, including whether the Minsk agreements should form the basis of the resolution or whether some minor adjustments have to be made to take into account local preferences.

Update the Helsinki Accords. Updating and modernizing the Helsinki Accords would cap a comprehensive settlement, laying the foundation for decades of peace in Europe. In particular, the two sides should seek agreement on the interpretation of the 10 principles guiding relations between states, to which all the parties agreed, including respect for sovereign rights, self-determination, noninterference in internal affairs, restraining from threats or use of force, and peaceful settlement of disputes. The goal is to establish a firm basis for the organization of European security going forward that takes into account historical developments and technological advances since 1975 that affect the way states relate to one another and act on the global stage.

Read full article here.

All good points in this article. Yet there is always a certain naiveté in the solutions proposed by these authors or by specialists like Anatol Lieven, whose proposals are similar, since they assume that the United States (or Great Britain) are actually interested in peace. We’re not there yet: there is at the present moment no real evidence of an interest in the American foreign policy community in its current configuration in such proposals.

I am born (1950) and raised in the United States. In my lifetime, a streak of deeply Neanderthal Russophobia in this community was always present, but the Phoenix-like reassertion of Russian power and influence in the last twenty years – especially against the background of the ascent of China to the status of the world’s premier economic powerhouse – has amplified this irrational sentiment to a decibel level I can’t remember, aided by what is now little more than government mass media. It is personified by people like Blinken, Nuland and Sullivan (if not the old Cold Warrior Biden himself), shared by most members of Congress, for whom being “tough on Russia” was always a cheap way of getting brownie points in domestic electoral contests, and is of course a perpetual boon for the military contractors from the era of “bomber gaps” and “missile gaps” of the 1960s and 1970s to the present propaganda fakery about a “Russian invasion of the Ukraine”.

I am quite certain that these are all people who would actually welcome a conflict of some sort in the Donbass as the best solution from several perspectives; in my view, the ultimate aim of the Ukrainian “project” was always to draw the Russian Federation into a “quagmire”. If, as seems likely to me, the Russian President will once again not show up for this “party”, there will certainly be some sort of provocation in order to force his hand.

“Russi delenda est!”.