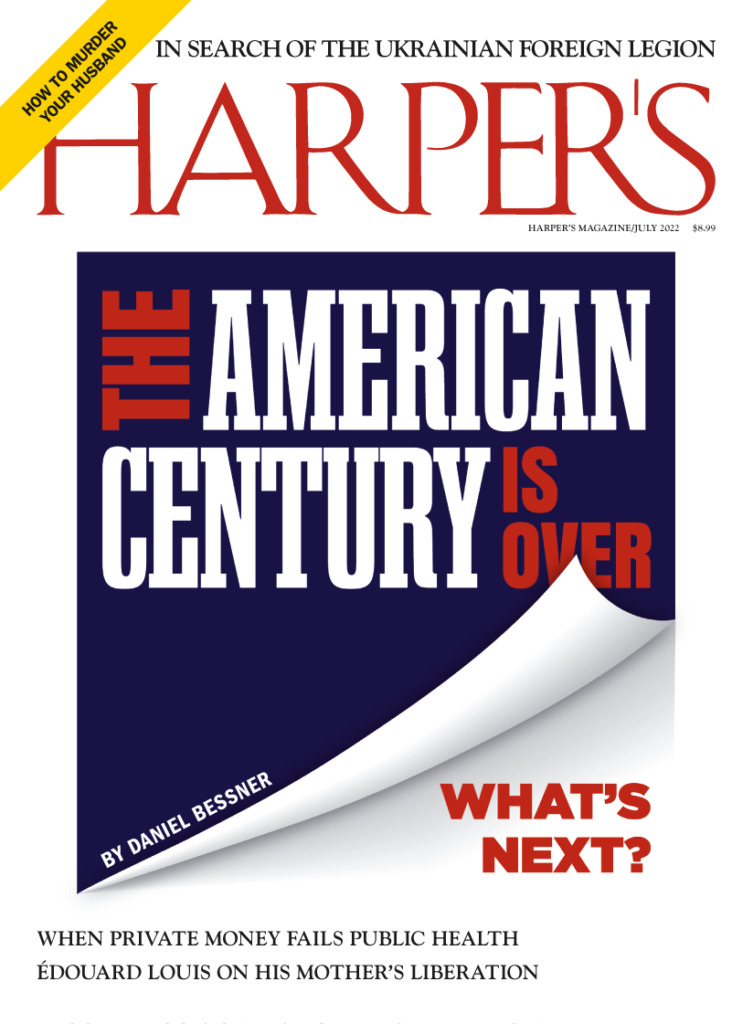

By Daniel Bessner, Harper’s, July 2022 Issue

In February 1941, as Adolf Hitler’s armies prepared to invade the Soviet Union, the Republican oligarch and publisher Henry Luce laid out a vision for global domination in an article titled the american century. World War II, he argued, was the result of the United States’ immature refusal to accept the mantle of world leadership after the British Empire had begun to deteriorate in the wake of World War I. American foolishness, the millionaire claimed, had provided space for Nazi Germany’s rise. The only way to rectify this mistake and prevent future conflict was for the United States to join the Allied effort and

accept wholeheartedly our duty and our opportunity as the most powerful and vital nation in the world and . . . exert upon the world the full impact of our influence, for such purposes as we see fit and by such means as we see fit.

Just as the United States had conquered the American West, the nation would subdue, civilize, and remake international relations.

Ten months after Luce published his essay, the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, and the United States, which had already been aiding the Allies, officially entered the war. Over the next four years, a broad swath of the foreign policy elite arrived at Luce’s conclusion: the only way to guarantee the world’s safety was for the United States to dominate it. By war’s end, Americans had accepted this righteous duty, of becoming, in Luce’s words, “the powerhouse . . . lifting the life of mankind from the level of the beasts to what the Psalmist called a little lower than the angels.” The American Century had arrived.

In the decades that followed, the United States implemented a grand strategy that the historian Stephen Wertheim has fittingly termed “armed primacy.” According to the strategy’s noble advocates, human flourishing, international order, and the future of liberal democratic capitalism depended on the nation spreading its tentacles across the world. Whereas the United States had been wary of embroiling itself in extra-hemispheric affairs prior to the twentieth century, Old Glory could now increasingly be seen flying across the globe. To facilitate their crusade, Americans constructed what the historian Daniel Immerwahr has dubbed a “pointillist empire.” While most empires traditionally relied on the seizure and occupation of vast territories, the United States built military bases around the world to project its power. From these outposts, it launched wars that killed millions, protected a capitalist system that benefited the wealthy, and threatened any power—democratic or otherwise—that had the temerity to disagree with it.

As Luce desired, by the end of the twentieth century, the United States, a nation founded after one of the first modern anticolonial revolutions, had become a world-spanning empire. The “city on a hill” had evolved into a fortified metropolis.

But in the past six years, two transformational events have begun to reshape the United States’ place in the world. First, the election of Donald Trump suggested to domestic and foreign audiences alike that the country might not be forever beholden to the idea that global “leadership” was a vital American interest. Instead of proclaiming the inviolability of the vaunted “liberal international order,” Trump approached international relations as any corrupt businessman would: he tried to get the most while giving the least. He thus withdrew from several international organizations and agreements—including the World Health Organization, the Paris climate agreement, the Iran nuclear deal, the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, and the Open Skies Treaty—and initiated trade wars intended to boost American business. Taken with his bellicose rhetoric, these actions demonstrated that the world could no longer assume that the United States was committed to defending the geopolitical status quo.

Second, the emergence of China as an economic and military powerhouse has decisively ended the “unipolar moment” of the Nineties and Aughts. The country only recently referred to as a “rising tiger” (Orientalism never dies) now boasts, according to some measures, the largest military and economy on earth. The Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and New Development Bank offer alternatives to the World Bank, International Monetary Fund, and other Western-dominated institutions, which, to put it mildly, aren’t exactly beloved in the Global South.

For the first time since the collapse of the Soviet Union, the United States confronts a nation whose model—a blend of state capitalism and Communist Party discipline—presents a genuine challenge to liberal democratic capitalism, which seems increasingly incapable of addressing the many crises that beset it. China’s rise, and the glimmers of the alternative world that might accompany it, make clear that Luce’s American Century is in its final days. It’s not obvious, however, what comes next. Are we doomed to witness the return of great power rivalry, in which the United States and China vie for influence? Or will the decline of U.S. power produce novel forms of international collaboration?

In these waning days of the American Century, Washington’s foreign policy establishment—the think tanks that define the limits of the possible—has splintered into two warring camps. Defending the status quo are the liberal internationalists, who insist that the United States should retain its position of global armed primacy. Against them stand the restrainers, who urge a fundamental rethinking of the U.S. approach to foreign policy, away from militarism and toward peaceful forms of international engagement. The outcome of this debate will determine whether the United States remains committed to an atavistic foreign policy ill-suited to the twenty-first century, or whether the nation will take seriously the disasters of the past decades, abandon the hubris that has caused so much suffering worldwide, and, finally, embrace a grand strategy of restraint.

The principles of liberal internationalism were first articulated by Woodrow Wilson as World War I limped along in April 1917. The American military, the president told a joint session of Congress, was a force that could be used to make the world “safe for democracy.” (The United States would decide, of course, which countries counted as democracies.) Wilson’s doctrine was informed by two main ideas: first, the Progressive Era fantasy that modern technologies and techniques—especially those borrowed from the social sciences—could enable the rational management of foreign affairs, and second, the notion that “a partnership of democratic nations” was the surest way to establish “a steadfast concert for peace.” Wilson’s two Democratic successors, Franklin Delano Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman, institutionalized their forebear’s approach, and since the Forties, every president save Trump has embraced some form of liberal internationalism. Even George W. Bush put together a “coalition of the willing” to invade Iraq and insisted that his wars were being waged to spread democracy.

Given liberal internationalism’s unquestioned dominance in the halls of power, it’s not surprising that the dogma still has the support of Washington’s most influential think tanks, which have never been known to bite the hand that feeds them. Members of the Council on Foreign Relations, the Brookings Institution, and the Center for a New American Security consider U.S. hegemony to be an essential condition for global peace and American prosperity. According to these stalwart backers of U.S. supremacy, the fact that a major war between great powers has not broken out since World War II indicates that U.S. hegemony has been, on balance, a force for good.

This is not to say that liberal internationalists are living in the past. They appreciate that, unlike during World War II or the Cold War, most countries agree on the rules of the game. Neither China, nor even Iran and Venezuela, reject the Western international order in the way that Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union did. While states may break rules to advance their interests, few countries are genuine pariahs; in fact, Russia and North Korea might be the only ones. In the modern era, even adversaries interact extensively. During the Cold War, the United States and Soviet Union barely traded with each other. Now, China is one of the United States’ largest trading partners.

This raises a question for liberal internationalists: How should the United States compete in this new world and contain “threats” to the established order? Unfortunately, most have converged on an answer from the past: whether they call it “democratic multilateralism,” “the strategy of reinvigorating the free world,” or “a fully developed democracy strategy,” liberal internationalists hope to establish a coalition of democracies akin to the one that existed during the Cold War, although this time centered on democracies (or, at least, non-autocracies) in the Global South. While claiming to reject the framing of a “new Cold War” with China that has permeated U.S. media, liberal internationalists promote what is effectively a Cold War-era strategy with a few more non-white countries added to the mix.

Like their Cold War predecessors, liberal internationalists believe that their struggle for democracy—and against China, which they regard as the major threat to U.S. power—will last indefinitely. As Michael Brown, Eric Chewning, and Pavneet Singh asserted in a recent Brookings Institution report, the United States must prepare for a “superpower marathon”—“an economic and technology race” with China that is unlikely to reach a “definitive conclusion.” American society, the liberal internationalists avow, will have to remain on a war footing for the foreseeable future. Peace is unthinkable.

The Chinese military, which employs more active personnel than that of any other nation, is of particular concern to liberal internationalists. To combat the threat of Chinese coercion in East Asia, they endorse a strategy in which the United States retains tens of thousands of troops in Japan and South Korea. This aggressive posture, they argue, will convince Chinese leaders that any anti-American actions they take will fail. And, ironically for those who have spent the past few years lambasting Russia for interfering in the 2016 presidential election, liberal internationalists also want to wage an information war against China, smuggling unflattering or damaging information into the country in an attempt to foment anticommunist dissent.

When it comes to the economy, liberal internationalists are bedeviled by the question of whether and how much to confront China—a country that has repeatedly stolen U.S. intellectual property and rejects liberal capitalist ideals of the free market. On one hand, they worry that China could wield its economic power to force other countries to abide by its wishes. On the other, they believe free exchange is vital to the United States’ economic health. Liberal internationalists thus recommend that the nation adopt an approach whereby it pressures China economically, but within the bounds of international rules, norms, and laws. In this way, they hope to combat China without discrediting liberalism writ large. As this suggests, liberal internationalists are well aware of the beating that American prestige has taken in recent years, especially after the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq and the 2008 financial crisis. If the United States is to dominate, it has to abide by rules that in the past it was all too happy to break.

In effect, liberal internationalists want to have it both ways, to challenge China without risking a shooting war or economic decoupling. The problem, however, is that international relations are not nearly as manageable as liberal internationalists assume. The Russian invasion of Ukraine—which was at least partially impelled by NATO expansion into Eastern Europe—is a clear example of the way in which behavior meant to deter war might very well incite it. Yet these basic facts are difficult for liberal internationalists to admit. For them, the American Century can only be restored by facing China head-on.

Restrainers, by contrast, understand that the American Century is over. They maintain that the expansive use of the U.S. military has benefited neither the United States nor the world, and that charting a positive course in the twenty-first century requires taking a root and branch approach to the principles that have guided U.S. foreign policy since World War II. Restrainers want to reduce the U.S. presence abroad, shrink the defense budget, restore Congress’s constitutional authority to declare war, and ensure that ordinary Americans actually have a say in what their country does abroad.

The origins of restraint can be traced to George Washington’s farewell address of September 1796, in which the president warned against “entang[ling] our peace and prosperity in the toils of European ambition, rivalship, interest, humor, or caprice.” Twenty-five years later, on July 4, 1821, the secretary of state, John Quincy Adams, likewise insisted that a defining characteristic of the United States was that it had “abstained from interference in the concerns of others. . . . She goes not abroad, in search of monsters to destroy.” Restraint remained popular for much of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries; during World War I, for instance, Wilson received substantial criticisms from those who argued that the United States should avoid undertaking messianic projects to remake the world. Of course, the history of U.S. foreign policy is far from one of restraint. From its beginnings, the United States expanded westward, displacing and killing indigenous peoples and eventually seizing a number of populated colonies in the Pacific and Caribbean.

Nevertheless, if restraint did not always apply in practice, the strategy attracted many adherents. Things changed during World War II, when restraint became associated with anti-Semitic “America Firsters,” politically marginal libertarians and pacifists, and discredited “isolationists.” In the Democratic Party, the former vice president Henry Wallace and other progressive restrainers were sidelined, as were Senator Robert A. Taft and other Republican anti-interventionists. Although restraint continued to percolate in social movements like the Vietnam War resistance of the Sixties and think tanks such as the Cato Institute and Institute for Policy Studies, it remained a negligible position until the foreign policy failures in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya.

In the wake of these blunders, interest in restraint has been reignited, as evidenced by the fact that two think tanks—Defense Priorities and the Quincy Institute, where I serve as an unpaid non-resident fellow—were recently founded with the goal of advocating for its fundamental principles. Gil Barndollar of Defense Priorities has usefully summarized the restrainers’ limited set of foreign policy goals: helping to realize “the security of the U.S. itself, free passage in the global commons, the security of U.S. treaty allies, and preventing the emergence of a Eurasian hegemon.” Because the major problems of the twenty-first century cannot be solved by U.S. military force, but instead require multilateral cooperation with nations that have adopted different political systems, there is no reason for the United States to promote democracy abroad or act as the global police force.

Accordingly, restrainers do not consider China an existential threat. When it comes to East Asia, their goal is to prevent war in the region so as to facilitate collaboration on global issues such as climate change and pandemics. This objective, they maintain, can be achieved without American hegemony.

Restrainers thus promote a “defensive, denial-oriented approach,” focused on using the U.S. military to prevent China from controlling East Asia’s air and seas. They also want to help regional partners develop the ability to resist China’s influence and power, and argue that the United States should place its forces far from the Chinese coast, in clearly defensive positions. A similarly hands-off approach applies to Taiwan and human rights. If China wants to seize Taiwan, restrainers assert, then the United States should not fight World War III to prevent it from doing so. If China wants to oppress its population, there’s not much that the United States can or should do about it.

The fundamental disagreement between the two schools of thought is this: liberal internationalists believe that the United States can manage and predict foreign affairs. Restrainers do not. For those of us in the latter camp, the withering away of the American Century cannot be reversed; it can only be accommodated.

The question of which strategy the United States should pursue is fundamentally a matter of historical interpretation. Was U.S. domination during the American Century good for the United States? Was it good for the world?

When one takes a long, hard look at U.S. foreign policy after 1945, it’s clear that the United States caused an enormous amount of suffering that a more restrained approach would have avoided. Some of these American-led fiascoes are infamous: the wars in Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq resulted in the death, displacement, and deracination of millions of people. Then there are the many lesser-known instances of the United States helping to install its preferred leaders abroad. During the Cold War alone, the nation imposed regime changes in Iran, Guatemala, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, British Guiana, South Vietnam, Bolivia, Brazil, Panama, Indonesia, Syria, and Chile.

As this record suggests, the Cold War was hardly “the long peace” that many liberal internationalists valorize. It was, rather, incredibly violent. The historian Paul Thomas Chamberlin estimates that at least twenty million people died in Cold War conflicts, the equivalent of 1,200 deaths a day for forty-five years. And U.S. intervention didn’t end with the Cold War. Including the conflicts in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, the United States intervened abroad one hundred and twenty-two times between 1990 and 2017, according to the Military Intervention Project at Tufts University. And as Brown University’s Costs of War Project has determined, the war on terror has been used to justify operations in almost half the world’s countries.

Such interventions obviously violated the principle of sovereignty—the very basis of international relations. But more importantly, they produced awful outcomes. As the political scientist Lindsey O’Rourke has underlined, countries targeted for regime change by the United States were more likely to experience civil wars, mass killings, human rights abuses, and democratic backsliding than those that were ignored.

When it comes to the benefits that ordinary Americans received from their empire, it’s similarly difficult to defend the historical record. It’s true that in the three decades after World War II, armed primacy ensured favorable trade conditions that allowed Americans to consume more than any other group in world history (causing incredible environmental damage in the process). But as the New Deal gave way to neoliberalism, the benefits of supremacy attenuated. Since the late Seventies, Americans have been suffering the negative consequences of empire—a militarized political culture, racism and xenophobia, police forces armed to the teeth with military-grade weaponry, a bloated defense budget, and endless wars—without receiving much in return, save for the psychic wages of living in the imperial metropole.

The more one considers the American Century, in fact, the more our tenure as global hegemon resembles a historical aberration. Geopolitical circumstances are unlikely to allow another country to become as powerful as the United States has been for much of the past seven decades. In 1945, when the nation first emerged triumphant on the world stage, its might was staggering. The United States produced half the world’s manufactured goods, was the source of one third of the world’s exports, served as the global creditor, enjoyed a nuclear monopoly, and controlled an unprecedented military colossus. Its closest competitor was a crippled Soviet Union struggling to recover from the loss of more than twenty million citizens and the devastation of significant amounts of its territory.

The United States’ power was similarly astounding after the Soviet Union’s collapse in the early Nineties, especially when one aggregates its strength with that of its Western allies. In 1992, the G7 countries—Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, the United Kingdom, and the United States—controlled 68 percent of global GDP, and maintained sophisticated militaries, which, the Gulf War seemed to demonstrate, could achieve their objectives quickly, cheaply, and with minimal loss of Western life.

But this is no longer the case. By 2020, the G7’s GDP had dwindled to 31 percent of the global total, and is expected to fall to 29 percent by 2024. This trend will likely continue. And if the past thirty years of American war have demonstrated anything, it’s that sophisticated militaries do not always achieve their intended political objectives. The United States and its allies aren’t what they once were. Hegemony was an anomaly, an accident of history unlikely to be repeated, at least in the foreseeable future.

There are also more fundamental, even ontological, problems with the liberal internationalist approach. Liberal internationalism is a product of the fin de siècle, when Progressive thinkers, activists, and policymakers across the political spectrum believed that rationality could achieve mastery over human affairs. But the dream proved to be just that. No nation, no matter how powerful, has the capacity to control international relations—an arena defined by radical uncertainty—in the ways that Woodrow Wilson and other Progressives hoped. The world is not a chessboard.

Furthermore, liberal internationalists’ democracy-first strategy assumes a Manichaean model of geopolitics that is both inconsistent and counterproductive. For all their crowing about democracy, liberal internationalists have been just fine collaborating with dictatorships, from Saudi Arabia to Egypt, when it has served perceived U.S. interests. This will probably remain true, making any kind of democracy-first strategy a primarily discursive one. Nonetheless, discursively centering democracy could have drastic repercussions. Dividing the world into “good” democracies and “bad” authoritarian regimes narrows the space for engagement with many countries not currently aligned with the United States. Decision-makers who view autocracies as inevitable opponents are less likely to take their interests seriously and may even misread their intentions. This happened repeatedly in the Fifties and Sixties, when U.S. officials insisted that the very nature of the Soviet system made it impossible to reach détente. In fact, détente was only achieved in the Seventies, after decision-makers concluded that the Soviet Union was best treated as a normal nation with normal interests, regardless of its political structure. Once Americans adopted this approach, it became clear that the Soviets, like them, preferred superpower stability to nuclear war.

Because it’s difficult to know precisely what a government like China’s is up to, liberal internationalists tend to flatten the complexities that shape its behavior, and assume that China will expand to the limits of its power. This idea owes much to the classical realist school of foreign policy, which, following the émigré political scientist Hans Morgenthau, maintains that nations have an animus dominandi, a will to dominate. (The United States, unsurprisingly, is assumed to act according to more noble motivations.) For this reason, some liberal internationalists claim, China will fill any power vacuum it can.

But is this an accurate description of China—or indeed, of any modern nation? Classical realism was born of the traumas of the Thirties, when two great powers, Nazi Germany and imperial Japan, considered the conquest of foreign territory vital to their futures. The experience of German and Japanese expansion profoundly shaped the work of midcentury thinkers like Morgenthau, who insisted that the search for lebensraum reflected more general laws of international relations.

Unfortunately for those liberal internationalists indebted to classical realism, states make the decisions they do for many reasons, from regime type (is a nation a democracy or an autocracy?) to individual psychology (is a particular leader mentally well?) to culture (what behavior does a given nation valorize?). When it comes to trying to explain why China—or Russia, or Iran, or North Korea—acts as it does, it’s not particularly useful to ignore everything that makes the country unique in favor of emphasizing immutable factors.

The historicist approach of restrainers is a far better way to analyze international relations. Restrainers focus on what China has done, and not what it might do; for them, China is a state that exists in the world, with its own interests and concerns, not an abstraction embodying transhistorical laws (which themselves reflect American anxieties).

And when examining what China has done, the evidence is clear: while the nation obviously wants to be a major power in East Asia, and while it hopes to one day conquer Taiwan, there’s little to suggest that, in the short term at least, it aims to replace the United States as the regional, let alone global, hegemon. Neither China’s increased military budget (which pales in comparison to the United States’ $800 billion) nor its foreign development aid (which is not linked to a recipient country’s politics) indicates that it desires domination. In fact, Chinese leaders, who tolerate the presence of tens of thousands of troops stationed near their borders, appear willing to allow the United States to remain a major player in Asia, something Americans would never countenance in the Western Hemisphere.

Ironically, liberal internationalists are imposing their own goals for hegemony onto China. Their commitment to armed primacy—a commitment that has led to war after war—threatens to increase tensions with a country that Americans must cooperate with to solve the real problems of the twenty-first century: climate change, pandemics, and inequality. When compared with these existential threats, the liberal internationalist obsession with primacy is a relic of a bygone era. For the sake of the world, we must move beyond it.

At the present moment, however, a majority of Americans side with the liberal internationalists: in a Pew poll taken in early 2020, 91 percent of American adults thought that “the U.S. as the world’s leading power would be better for the world,” up from 88 percent in 2018.

Nonetheless, there’s a growing generational divide over the future of U.S. foreign policy. A 2017 survey by the Chicago Council on Global Affairs, for instance, discovered that only 44 percent of millennials believe that it’s “very important” for the United States to maintain “superior military power worldwide,” compared with 64 percent of boomers. In a poll from 2019, zoomers and millennials were more likely than boomers to agree that “it would be acceptable if another country became as militarily powerful as the U.S.”

The fact that younger Americans are waking up to the manifold and manifest failures of liberal internationalism presents the United States with an enormous opportunity: it can abandon an irresponsible and hubristic liberal internationalism for restraint. This will, admittedly, be a difficult task. Americans have ruled the world for so long that they see it as their right and duty to do so (especially since most don’t have to fight their nation’s wars). Members of Congress, meanwhile, get quite a bit of money, and their districts even get a few jobs, from defense contractors. Both retired generals and pointy-headed intellectuals rely on the defense industry for employment. And restraint is still a minority position in the major political parties.

It’s an open question whether U.S. foreign policy can transform in a way that fully reflects an understanding of the drawbacks of empire and the benefits of a less violent approach to the world. But policymakers must plan for a future beyond the American Century, and reckon with the fact that attempts to relive the glories of an inglorious past will not only be met with frustration, but could even lead to war.

The American Century did not achieve the lofty goals that oligarchs such as Henry Luce set out for it. But it did demonstrate that attempts to rule the world through force will fail. The task for the next hundred years will be to create not an American Century, but a Global Century, in which U.S. power is not only restrained but reduced, and in which every nation is dedicated to solving the problems that threaten us all. As the title of a best-selling book from 1946 declared, before the Cold War precluded any attempts at genuine international cooperation, we will either have “one world or none.”

Daniel Bessner is an associate professor at the University of Washington’s Henry M. Jackson School of International Studies.