Order the book here.

By Black Northern, The Burkean (Ireland), 5/23/22

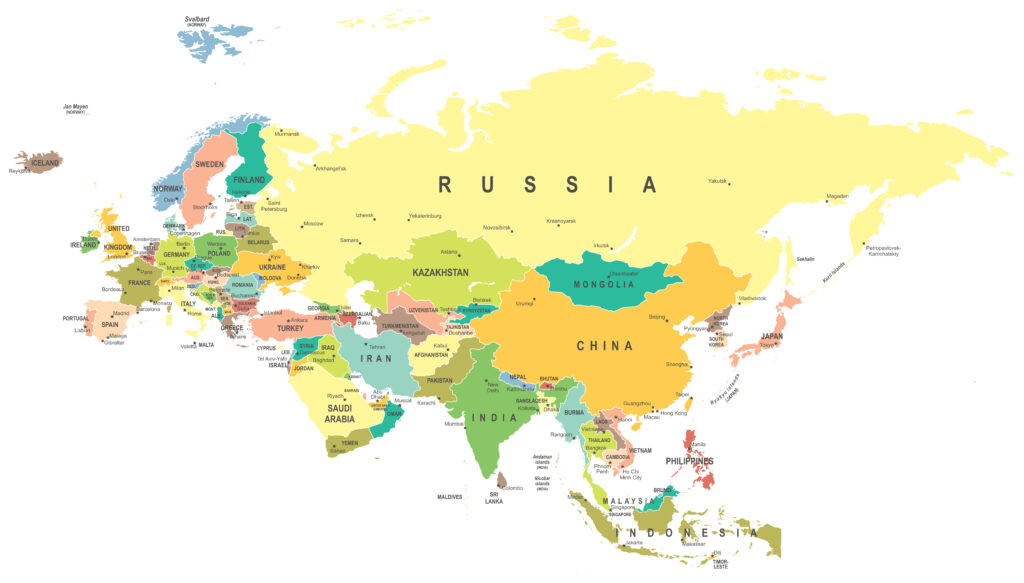

What rages today is the largest conventional conflict in the European continent since the Second World War, fought by around half a million soldiers serving almost two hundred million people for a territory nearly ten times the size of the whole island of Ireland, yet surprisingly scant primary source material on the roots of the present Russo-Ukrainian conflict exists in either Russian or Ukrainian, let alone in English.

The YouTuber Ian McCollum, who runs the Forgotten Weapons gun channel with almost 2.5 million subscribers, had announced at the very eve of the official Russian invasion his intent to publish The Foreigner Group, a first-hand memoir of the conflict by a Swedish foreign volunteer Carolus Andersson, who served in the ranks of the Ukrainian Azov Battalion. His announcement however sparked controversy amongst his large fanbase, due to the Azov Battalion’s adjacency with National Socialism and Andersson’s own right-wing beliefs, and McCollum eventually cancelled the project. As of writing this however, The Foreigner Group is set to be published instead by Antelope Hill Publishing, who have also recently published Chechen Blues, an account of the First Chechen War of 1994 by Russian journalist Alexander Prokhanov.

This all being said, Nemets (@Peter_Nimitz), a rather eccentric yet affable history book account with just over 50,000 followers on Twitter, has recently done a great service to preserving the historiography of the conflict by translating one of the seminal works of pro-Russian separatist literature into English, 85 Days in Slavyansk by Alexander Zhuchkovsky.

Zhuchkovsky, who fought himself alongside the militants of the newly-proclaimed Donetsk’s People Republic (DPR), sought to write the first book of its kind to examine in depth the Battle of Slavyansk, the first engagement of what would become an eight-year protracted conflict between the Ukrainian government and pro-Russian separatists in the Donbass region of the south-east, comprising the oblasts (regions) of Donetsk and Lugansk.

It is unapologetically a pro-separatist account, but a remarkably sober and honest one, a work that is not intended to be consumed in the vein of propaganda, and a work which consults an impressively vast array of Russian, separatist and even Ukrainian sources as well as extensive interviews with many of the prominent separatist commanders and fighters. One such figure ‘inextricably linked to the Donbass Uprising’, cuts head and shoulders above the rest, a constant presence in almost every single chapter, and a figure so prominent that a faithful retelling of Slavyansk could not be told without.

On 12 April 2014, 52 masked volunteers, commanded by its quiet yet imposing leader, Igor Strelkov, crossed the Russo-Ukrainian border, entered the large city of Slavyansk in the Donetsk Oblast, populated by around 100,000 people, and quickly surrounded the offices of the Interior Ministry in the city where a small police garrison were stationed.

After a brief exchange of gunfire, the police garrison swiftly surrendered, were detained, disarmed and quickly released. The militants would in the succeeding hours gradually seize control of the city’s civil administration buildings, its police headquarters and the offices of the SBU, the Ukrainian Security Service. By the end of April 12, Strelkov and his men had seized the city of Slavyansk without bloodshed and almost without a single shot fired.

‘Strelkov’ was only Igor Girkin’s nom de guerre, yet of the man Igor Girkin, very little was known. He was born and educated in Moscow, and was a soldier by profession, having served with Russian peacekeepers in the Moldovan breakaway region of Transnistria, a foreign volunteer for the ethnic Serbian separatists Republika Srpska in the Bosnian War, as well as a regular Russian soldier fighting in both the First and Second Chechen Wars.

He had also worked for the FSB, the Russian state’s successor to the KGB of the Soviet Union, in both operational and managerial capacities for around seventeen years, varying from playing an active role in counter-insurgency operations in the recently re-conquered Chechenya to more mundane bureaucratic work based out of the capital.

‘War was Strelkov’s native habitat,’, Zhuchkovsky writes of Strelkov, ‘He had grown from a bookish boy to a specialist in small wars and paramilitaries. When not at war, he had to make his own by participating in historical re-enactments, decked out as a monarchist Che Guevara with the epaulettes of the army of the old Russian Empire. It says a great deal about Strelkov’s idealism and nobility that he never became a pure mercenary, working indiscriminately for any faction.’

Strelkov is also ideologically quite eccentric even for a political landscape that had spawned the likes of National Bolshevism, a neo-monarchist committed to the restoration of the Russian monarchy that had been deposed by the 1917 Revolution, as well as an irredentist seeking the re-establishment of a Greater Russia to encompass Belarus, Ukraine and other Russian lands, with the remaining rump of the old Soviet Union to be an ‘unconditional zone of Russian influence.’

Strelkov today enjoys a semi-sacred status for his command of the defence of Slavyansk, a cult of personality which the reserved and rather humble Strelkov eventually found himself unnerved by. The events of Slavyansk however transformed him into a nihilist, his reflections of the many failures, little and big, that led ultimately to the separatists’ retreat made him utterly distrustful of both the separatists and the Russian state, a distrust and fatalism which has stayed with him even when analysing the current war.

Zhuchkovsky found Strelkov to be evasive when asked on whether he acted alone or with the tacit support of the Russian government. Some months earlier, Strelkov had played an instrumental yet discreet role in the bloodless Russian annexation of Crimea and in one of the only answers he would give to Zhuchkovsky on the matter, seemed to suggest that the Russian-installed head of the Republic of Crimea Sergey Aksyonov had given his personal blessing to Strelkov’s operation.

Zhuchkovsky himself is at difficulty as to the question, for although it was implausible that a mere ragtag group of fifty-two volunteers acting alone could capture a city of 100,000 without bloodshed, it was also similarly implausible that the Russian state played any significant role, for they would have sent forces in the thousands as in Crimea rather than in the mere dozens.

Alexander Boroday, who would become the first Prime Minister of the Donetsk’s People Republic, writes interestingly of the attempt by himself and ‘some comrades in Moscow’ to recall Strelkov so as to suspend or outright cancel the operation:

‘I left the airport, got into a car, and called Strelkov on his cell phone. The call didn’t go through. I found out later that Strelkov had turned his phone off. He had foreseen this development, and had no intention of changing his plan for the Donbass.’

He writes further on the general opinion of the Russian state regarding the Donbass:

‘The support for Russian annexation was both less intense and less widespread than in Crimea. It was also apparent that there would be no repetition of the Crimean scenario in Donbass. Yes, a majority of the people in Donbass wanted to join Russia, yes there were large protests, but Russia herself hadn’t decided if the Donbass was worthy of involvement. We wanted to wait for the outcome of the protests before making a decision, and decided to slow Strelkov’s operation down. Strelkov had his own opinions, and rushed forward.’

A rational analysis fails to give Zhuchkovsky any real closure, yet such an analysis must assume that the Russian state was acting rationally, which cannot always be certain since states, like the men who create and govern states, are not always rational beings. Strelkov, for instance, argues that Vladimir Putin had effectively crossed the rubicon at Crimea yet inexplicably stopped short at the Donbass, and that the failure of the Russian government to strike while the iron was still hot in 2014 had condemned the separatists at Slavyansk to a long protracted conflict spanning years rather than a swift and decisive seizure of power that might have spanned only days.

The volunteers at Slavyansk on April 12 were largely welcomed by the majority Russian-speaking population, and the volunteer ranks would swell from its original 52 to around a peak of 2,500. Largely made up of the local population, the separatist force also included a large contingent of ordinary Russian volunteers (around 40% were Russian citizens by end of June) as well as a smattering of volunteers from further afield.

A military administration would be established by Strelkov in the following days, enforcing curfews, armed patrols and restricting the sale of alcohol. Military courts were established and the death penalty became a de facto punishment in the city. Interestingly however, conscription, with the exception of local delinquents, was not enforced and the separatist force remained organised on a volunteer basis. Much to the chagrin of Strelkov, large sections of the population did not join the separatist militia, for many it was out of continued loyalty to the Ukrainian government, although Strelkov suspected that general lethargy also played its part.

‘Twenty four men, six of them officers, came from the Union of Afghanistan Veterans. They said they were ready to serve, but requested they be held in reserve near their homes rather than sent to the front line. I thanked them, but told them that we needed men who would listen to orders and fight where they were needed. Only three of them, only one an officer, ended up in the militia. The rest decided it was too inconvenient.’

In the early stages of the crisis, there was regular contact between the separatists and local soldiers serving in the Ukrainian Army, many of whom were seriously considering defection. They knew the separatists well, they were family, neighbours, friends from their school years and so on. The reorganisation of the Ukrainian forces, replacing these more locally based soldiers with more nationalistic troops from the Ukrainian-speaking western provinces largely prevented any such mass defection from occurring.

On April 13, the separatists ambushed an elite Alpha GRU unit eight kilometres to the north of Slavyansk at a checkpoint near the small village of Semyonovka, killing one and wounding four. The Ukrainians were so taken aback by the attack that for many weeks afterwards believed their assailants to have been Russian Spetsnaz, and led to a general overcautiousness amongst the Ukrainian troops who believed that storming the city would lead to a direct conflict with the Russian Armed Forces.

The general belief amongst many of the separatists and indeed the local population was that the Russians would eventually formally intervene, yet as time passed, it become more evident that the Russians would not intervene. On April 17, the Russian Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov formally agreed with his Ukrainian counterpart that all illegal armed groups were to be disarmed and that all armed actions were to be suspended.

Hopes were raised by a Russian military exercise being conducted in the bordering Rostov region, yet were quickly dashed again. The locals of Slavyansk waited intently for a formal move on Victory Day yet no Russian troops arrived. Repeated appeals by Strelkov, who had finally revealed himself to the public in a press conference on April 26, for Russian intervention were ignored, and following the Ukrainian presidential elections on May 25, Vladimir Putin formally recognised the winner Petro Poroshenko as the legitimate president of Ukraine. A month later, the decree which authorised Putin to use Russian military force in Crimea and therefore would have authorised Russian intervention in the Donbass was revoked by the Russian Parliament.

The aspirations of the separatists were not federalisation or independent republics, but re-unification with Russia proper, yet without Russian commitment, they had little choice but to fall back on independence. Two referendums were held in Donetsk and Lugansk respectively, several weeks before the Ukrainian presidential election, both returned overwhelming majorities in favour of independence, both votes however were believed by international observers to be heavily rigged and therefore illegitimate.

The tentativeness of the Ukrainians began to slowly wear off as they became more confident and therefore more aggressive, seizing back nearby villages as well as commencing artillery bombardment on the city itself. The TV tower overlooking the city at Mount Karachun was seized from a small unit of only twelve separatist defenders, and used as a Ukrainian artillery post. Small groups of saboteurs would be also deployed inside the city, assisted no doubt by the pro-Ukrainian loyalist elements of Slavyansk.

The defence of the city, now effectively under siege, relied on weaponry that had been mainly pilfered from the Ukrainians; guns, artillery, MANPADs etc. Separatist communications were unencrypted and therefore listened in at all times by the Ukrainians. The separatists, knowing that a full frontal assault on the city would result in their rout, employed the age-old tactic of deception; ‘Appear weak when you are strong, and appear strong when you are weak.’ Strelkov, keenly aware that his communications were being monitored, would grossly exaggerate the strength of the militia and play up to the Ukrainian belief that the Russian Armed Forces were in Slavyansk during phone calls.

‘He would reference well-armed companies where there were only poorly-equipped platoons, hoping to demoralise the Ukrainians with tales of an invincible force of Russian mercenaries. Strelkov’s years of experience in the special forces had not been in vain.’

Like all great war memoirs, we have our fair share of characters, the eccentrics, the ideologues, even the fools. One of the most compelling figures frequently mentioned is ‘Motorola’, or Arseny Pavlov, one of the more semi-legendary figures of the separatist struggle.

Motorola, affectionally known as ‘the red-headed separatist’, had formed one of the original 52 who had captured Slavyansk. He was an ethnic Komi, one of the Finnic peoples of Russia, born in the Komi Province and had been in the Russian Army, serving two tours in Chechnya. He had been one of the reconnaissance platoon that had successfully ambushed the most elite unit of the GRU on April 13. He would assume command of said reconnaissance platoon which quickly swelled into the most effective heavy weapons unit in the separatist militia, of around 200 men.

He had a notorious reputation for psychological warfare; often recording his skirmishes with the Ukrainian forces with a GoPro camera and sending the footage to Russian journalists for publication as well as claiming Chechen Kadyrovites were fighting alongside the separatists, often screaming ‘Allahu Akhbar!’ in battle and broadcasting Islamic calls to prayer every few hours as to instil fear into the Ukrainians. Alexander Kots, the military correspondent for the Russian newspaper Komsomolskaya Pravda writes of Motorola:

‘There are men who fight in bloody battles and survive, but with broken souls and constant cynicism. And there are those who cannot only love and war, but also keep possession of themselves. Motorola is one such man – a fighter from God, a joker, and a lover of Russian rap.’

Motorola would be killed several years later by an IED explosion in his Donetsk apartment, the exact perpetrators to this day unknown.

Another interesting figure that made up the original 52 was ‘Vandal’, in fact a sixteen-year old field medic Andrey Savelyev from Kiev, who gained a reputation for his heroic bravery in rescuing his mortally wounded commander ‘Bear’ whilst under Ukrainian fire. He had been initially refused several times by Strelkov whilst in Crimea, yet his persistence paid off and he was despatched to Slavyansk.

There is also Zhuchkovsky himself; Zhuchkovsky, a native of Saint Petersburg, joined the separatists at Slavyansk following a Strelkov appeal for more men, having been initially stationed at Lugansk. He had narrowly escaped death by shelling twice, once by a few minutes and once by only a few seconds. Near the tail end of the battle, whilst accompanying new Russian recruits to the frontline, his minibus was ambushed by Ukrainian forces. Although Zhuchkovsky and his men escaped with their lives, two of the recruits were killed, their mangled bodies charred beyond recognition and only identifiable by process of deduction.

By July, the position of the separatists had become untenable as the Ukrainians completed their encirclement of the city. Strelkov, by July 4, ordered a withdrawal from the city southwards to Kramatorsk, breaking through the encirclement and thus ending the Battle of Slavyansk after 85 days.

Although the battle of Slavyansk had ended in defeat, the wider struggle had only begun. Eight years of grinding warfare later, Russia has finally crossed the Rubicon and their troops are within twenty miles of Slavyansk, inching ever closer by the day. Strelkov may live to see the day where the Russian flag is finally once more hoisted over Slavyansk, yet it will have come at a personal cost to himself having made too many enemies over the years, but perhaps it will have been at an even graver cost for the many thousands dead since, including Motorola, that may have lived had the Russians taken action eight years ago as Strelkov so desperately appealed.

Separatism is a fine art that the Irish are masters of, and many of the themes evoked in this memoir appeal very deeply to the Irish nationalist; the sense of betrayal the separatists felt at the ambivalence of their motherland is something that as a nationalist from the North appealed to me especially so. But what most struck me and what, I think, will strike the average reader is that 52 men shaped not only the destiny of a country, or even of two countries, but that of an entire continent.

There is little criticism to be made regarding such a highly valuable work that has been re-published and translated at such an important juncture in perhaps the entire history of European civilization. To make petty criticisms here and there would be to nip at ankles. I salute Mr. Nemets for his commendable work in translating Mr. Zhuchkovsky’s excellent memoir. I shall hope that many such memoirs, whether they be the testaments of Russians or Ukrainians, will be published in the coming future.