By Caitlin Johnstone, Substack, 1/11/22

Research conducted by New York University’s Center for Social Media and Politics into Russian trolling behavior on Twitter in the lead-up to the 2016 US presidential election has found “no evidence of a meaningful relationship between exposure to the Russian foreign influence campaign and changes in attitudes, polarization, or voting behavior.”

Which is to say that all the years of hysterical shrieking about Russian trolls interfering in US democracy and corrupting the fragile little minds of Americans — a narrative that has been used to drum up support for internet censorship and ever-increasing US government involvement in the regulation of online speech — was false.

And to be clear, this isn’t actually news. It was established years ago that the St Petersburg-based Internet Research Agency could not possibly have had any meaningful impact on the 2016 election, because the scope of its operations was quite small, its posts were mostly unrelated to the election and many were posted after the election occurred, and its funding was dwarfed by orders of magnitude by domestic campaigns to influence the election outcome.

What’s different this time around, six years after Trump’s inauguration, is that this time the mass media are reporting on these findings.

The Washington Post has an article out with the brazenly misleading headline “Russian trolls on Twitter had little influence on 2016 voters“. Anyone who reads the article itself will find its author Tim Starks acknowledges that “Russian accounts had no measurable impact in changing minds or influencing voter behavior,” but the insertion of the word “little” means anyone who just reads the headline (the overwhelming majority of people encountering the article) will come away with the impression that Russian trolls still had some influence on 2016 voters.

“Little influence” could mean anything shy of tremendous influence. But the study did not find that Russian trolls had “little influence” over the election; it failed to find any measurable influence at all.

Starks does some spin work of his own in a bid to salvage the reputation of the ever-crumbling Russiagate narrative, eagerly pointing out that the report does not explicitly say Russia definitely had zero influence on the election’s outcome, that it doesn’t examine Russian trolling behavior on Facebook, that it doesn’t address “Russian hack-and-leak operations,” and that it doesn’t say “doesn’t suggest that foreign influence operations aren’t a threat at all.”

None of these are valid arguments. Claiming Russia definitely had no influence on the election at all would have been beyond the scope of the study, the report’s authors do in fact argue that the effects of Russian trolling on Facebook were likely the same as on Twitter, the (still completely unproven) “Russian hack-and-leak operations” were outside the scope of the study, as is the question of whether foreign influence operations can be a threat in general.

What Starks does not do is make any attempt to address the fact that mainstream news and punditry was dominated for years by claims that Russian internet trolls won the election for Donald Trump. He does not, for example, make any mention of his own 2019 Politico article telling readers that the Russian Twitter troll operation ahead of the 2016 election “was larger, more coordinated and more effective than previously known.”

Starks also does not take the time to inform The Washington Post’s readership about the false reporting this story has received over the years from his fellow mainstream news media employees, like The Washington Post’s David Ignatius and his melodramatic description of the St Petersburg troll farm as “a sophisticated, multilevel Russian effort to use every available tool of our open society to create resentment, mistrust and social disorder” in an article hysterically titled “How Russia used the Internet to perfect its dark arts“. Or The New York Times’ Michelle Goldberg in her article “Yes, Russian Trolls Helped Elect Trump“, in which she argues that it looks increasingly as though the Internet Research Agency “changed the direction of American history.” Or NBC’s Ken Dilanian (a known CIA asset), who described Russian trolling on Twitter in the lead-up to the election as “a vast, coordinated campaign that was incredibly successful at pushing out and amplifying its messages,” a claim that was then repeated by The Washington Post. To pick just a few out of basically limitless possible examples.

Starks and his editors could easily have included this sort of information in the article. It would have greatly helped improve clarity and understanding among The Washington Post’s audience if they had. It would have been entirely possible to clearly spell out the fact that all those other reports appear to have been incorrect in light of this new information, or at least to acknowledge the fact that there is a glaring difference between this new report and previous reporting. It would do a lot of good for awareness to grow, especially among Washington Post readers, that there’s been a lot of inaccurate information circulating about Russia and the 2016 election these past several years.

But they didn’t. And nobody else in the mass media has done so either. Even The Intercept’s report on the same story, despite having the far more honest headline “Those Russian Twitter bots didn’t do $#!% in 2016, says new study,” doesn’t name any names or criticize any outlets for their inaccurate reporting on Russian trolls stealing the election for Donald Trump.

Indeed, it’s very rare in the west to see mainstream journalists hold other mainstream journalists accountable for their false reporting, facilitation of propaganda, or journalistic malpractice, unless it’s journalists whose approval they don’t care about like members of the opposite political faction or independant media reporters. This is because western journalists are worthless, obsequious cowards whose entire lives revolve around seeking the approval of their peers.

The most important reporting a journalist can do in the western world today is help expose the lies, propaganda and malpractice of other western journalists and news outlets. But that is also the last thing a western journalist is ever likely to do, because western journalists seek praise and approval not from the public, but from other western journalists.

You can see this in the way they post on Twitter, with their little in-jokes and insider references, how they’re always cliquing up and beckoning and signaling to each other. Twitter is a great window through which to observe western journalists, because they really lay it all out there. Watch their bootlicking facilitation of status quo power, their ingratiating tail-wagging with each other, the way they gang up on dissenters like zealots burning a heretic. To see what I’m talking about you have to pay attention not to their viral tweets that go off but to all the rest that receive little attention, because the ones that take off are the ones the public are interested in. If you watch them carefully it becomes clear that for most of them the intended audience of the majority of their posts is not the rank-and-file public, but their fellow members of the media class.

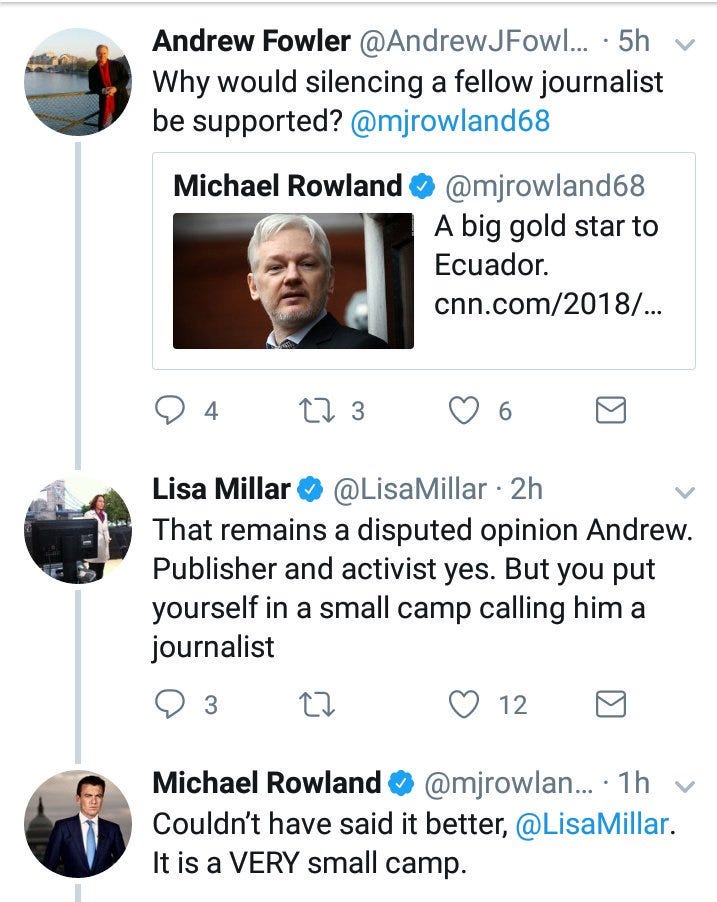

Look at this Twitter conversation between Australian journalists right after the Ecuadorian embassy cut off Julian Assange’s internet access in 2018 for a good illustration of this. Former ABC reporter Andrew Fowler (now a vocal supporter of Assange) questions ABC’s Michael Rowland for applauding Ecuador’s move, and ABC’s Lisa Millar rushes in to help Rowland argue that Assange is not a journalist and doesn’t deserve the solidarity of journalists, and that Fowler is putting himself on the outside of the groupthink consensus by claiming otherwise. Millar and Rowland are part of the clique, Fowler is being ostracised from it, and Assange is the heretic whose lynching they’re braying for:

Western journalists have a freakish herd-like mindset that makes the derision and rejection of their class the most nightmarish scenario possible and the approval of their class the most powerful opiate imaginable. They’re terrified of other journalists turning against them, of being rejected by the people whose approval they crave like a drug, of being kicked out of the group chat. And that’s exactly what would happen if they began leveling valid criticisms at mass media propaganda in public. And that’s exactly why that doesn’t happen.

The western media class is a cloistered, incestuous circle jerk that only cares about impressing other members of the cloistered, incestuous circle jerk. It doesn’t care about creating an informed populace or holding the powerful to account, it cares about approval, inclusion and acclaim from its own ranks, regardless of what propagandistic reporting is required to obtain it. The Pulitzers are mostly just a bunch of empire propagandists giving each other trophies for being good at empire propaganda.

A journalist with real integrity would spurn the approval of the media class. It would nauseate and repel them, because it would mean you’ve been aligning yourself with the most powerful empire in history and the propaganda machine which greases its wheels. They would actively make an enemy of the mainstream western press.

Journalists without integrity — which is to say the overwhelming majority of journalists — do the opposite.

None of this will be news to any of my regular readers, who will likely understand that the role of the mass media is not to inform but to manufacture consent for the agendas and interests of our rulers. But we shouldn’t get used to it, or lose sight of how odious it is.

It’s important to be clear about how gross these people are. You can never be sufficiently disdainful of these freaks.