By Ben Aris, Intellinews, 4/16/23

Russia is already a mining and minerals titan but as the green and EV revolutions unfold its position will only improve as metals and minerals gradually replace hydrocarbons as the country’s major exports and give the Kremlin fresh leverage over the rest of the world.

“While the country is already a leading producer of gas and oil, it possesses vast geological resources, including significant deposits of diamonds, gold, platinum, palladium and coal, as well as reserves of iron, manganese, chromium, nickel, titanium, copper, tin, lead and tungsten ores. These resources are estimated to represent a total value equivalent to $75 trillion, potentially making Russia the world’s richest country,” according to a report highlighting Russia’s potential to become a major player in the global mining industry from the French Institute of International Relations (IFRI).

Demand for raw materials on the international market is growing exponentially as a result of surging trade flows, demographic growth in emerging countries and ecological transition policies. The new renewables and electric vehicle (EV) industries are mineral intensive, changing the traditional demand profile in the extractive industries. And Russia is home to nearly every element found on the periodic table in vast quantities.

“The extraction of metals provides the necessary elements for energy, communication, transport and other infrastructure. The mass adoption of “green technologies”, such as electric vehicles and renewable energies (such as wind and solar power), is bringing about a further increase in global demand for metals,” says IFRI. “However, Russia’s mining sector currently faces significant challenges. Its largely privatised industry is hindered by obsolete infrastructure, insufficient investment and a shortage of qualified human resources. The situation may be further exacerbated by the war in Ukraine.”

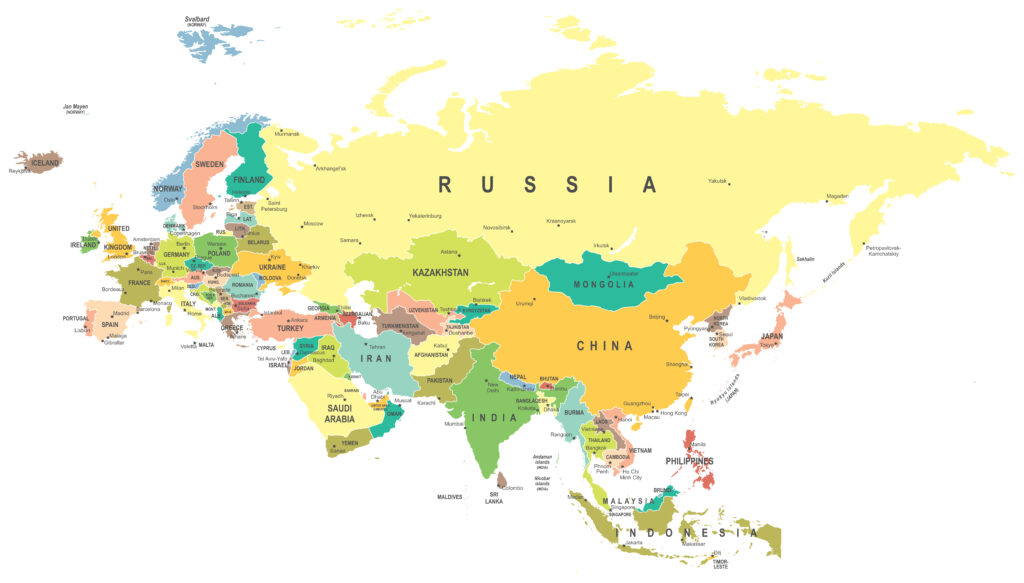

In a context of growing global demand for critical metals and minerals to meet the challenge of the ecological and energy transition, the future of Russia’s mining industry depends on a comprehensive modernisation process that has yet to begin in earnest and on a reorientation towards new markets in Asian such as India, Malaysia and Vietnam, and Africa, where the growth is fastest. All these countries have retained their economic ties with Russia, despite the sanctions, and are looking to boost their mineral supplies.

For the Kremlin’s part, it is looking at the mining sector to boost revenues and slowly replace its dependency on hydrocarbons as a new source of revenues. This change is already well underway.

Over the last five years, Russia’s extractive economy has accounted for 58.6% of the total value of Russian exports, broken down as follows: crude oil (26.4%), refined oil products (16.5%), natural gas (10.5%) and ferrous metals (5.3%).

And there is plenty of scope to expand extraction. Russia holds the world’s third-largest reserve of nickel, fourth-largest reserves of uranium, and especially copper, which is predicted to see a rise in global demand of 275% to 350% by 2050 thanks to the advent of the EV industry.

“Russia’s mining industry has the potential to become a strategic sector that is not affected by sanctions,” says IFRI.

Modernisation and the environment

Russia’s extractive segment plays a vital role in the country’s overall economy, with nearly 17,000 businesses involved in the sector. Out of these, 3,000 companies are engaged in the extraction of metal ores, while 800 are dedicated to coal mining. The majority of these businesses, around 16,300, belong to Russian stakeholders, with only 200 owned by foreign or joint entities, and 100 owned by public bodies. In addition, Russia has 39,800 businesses involved in the transformation of metals, IFRI reports.

As the mining sector is considered to be strategic, the government tightly controls foreign investment. It has the right of review over any direct or indirect acquisition of a domestic company by foreign investors that reaches or exceeds 25% of the firm’s voting share capital. Foreign government-owned entities face even tighter restrictions, with any acquisition that exceeds 5% subject to a special authorisation and also capped at 25%.

Furthermore, foreign companies cannot directly hold mining rights for deposits considered “strategic” and of “federal importance”, according to the law on subsoil. The Ministry of Natural Resources and the Environment, the Federal Agency for Subsoil Use and the Federal Agency for the Oversight of Natural Resources oversee the institutional architecture of the mining sector.

The main challenge is that almost the entire sector relies on infrastructure inherited from the Soviet era, which is highly polluting and obsolete. Mining regions, such as Norilsk in the Far North and the coal-rich Kuznetsk Basin in the south, are ecological disaster zones. And the sector has not executed its modernisation strategy, which is necessary for securing its technology transfer chains in the long term, reports IFRI.

There has been some progress as the Kremlin tries to incentivise modernisation and an environmental clean-up. The Kuznetsk Basin region has one of the world’s largest coal deposits, with proven reserves of approximately 693bn tonnes, accounting for half of the country’s annual coal output. Small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) within the Kuzbass Technopark are encouraged to invest in R&D via tax breaks and an exemption from property tax. The Kuzbass university and research centre also offer R&D mechanisms aimed at improving the competitiveness of the coal sector. But these programmes have produced few tangible results.

Bigger listed businesses in the sector are also making substantial efforts to transform their industrial equipment to comply with international standards as ESG awareness grows and increasingly affects share prices. For example, Norilsk Nickel, the state-owned nuclear power company Rosatom, and diamond miner Alrosa are investing heavily in modernising their infrastructure, with Norilsk Nickel intending to invest RUB100bn €1.3bn) between 2020 and 2024 to modernise its energy complex. Norilsk Nickel has been one of the most active, after the Norwegian State Pension fund banned investments into its shares on poor ESG results grounds.

Logistical bottlenecks

While there is no shortage of deposits, the difficulty is accessing them and then getting the minerals out to the global markets. Most of the deposits are located deep in Russia’s frozen interior.

“Russia has vast deposits of raw materials, but they are difficult to exploit due to inadequate infrastructure. However, the Russian government has not yet initiated a major works policy aimed at remedying it,” IFRI says.

Russia’s railway network, which is a critical part of the logistics chain, has several weaknesses and limited capacity. The railway network suffers from a lack of competitiveness, unreliable investments, poor flow capacity and an absence of bridges, which are essential for the viability and continuity of transport chains throughout the country, reports IFRI.

Another problem is the privatisations of the 1990s, and the federal nature of Russia’s government has created a confusing welter of actors.

“Firstly, the diversity of the actors involved in the sector and the variety of minerals exploited make the development of a systemic investment policy complex. Secondly, the dysfunctional relations between the federal government and local and regional institutions can hinder the progress of infrastructure projects,” says IFRI.

The Russian government has yet to initiate a major unified works policy aimed at remedying the situation. The problem of transportation infrastructure particularly affects mining projects in the Arctic and the Far East.

Siberia illustrates the challenges faced in improving the transportation network, says IFRI. In 2020, 144mn tonnes of freight passed through the Siberian part of the railway network. The ongoing modernisation of the region’s network aims to increase this volume to 180mn tonnes by 2025. However, the consequences of the war in Ukraine has further destabilised certain rail network development projects, such as the new expansion of the freight hub (Vostočnyj poligon) in eastern Siberia. Unable to sell goods to the West thanks to sanctions, Russia’s rail system has become clogged as the volumes of bulk cargo headed east have ballooned.

“Alongside the development of road and rail infrastructure, the federal authorities are targeting the Northern Sea Route (NSR), a critical hub for Russia’s geopolitical, economic and military ambitions. Maritime transport, particularly via the NSR, gives rise to more flexible flow management, thereby making it possible to meet demand from markets located far away from Russian territory, such as Malaysia and Vietnam,” says IFRI.

Mining in the Arctic

The largely untapped Arctic territories are a key focus for the development of Russia’s extractive industries.

Since 2014, thanks to the global dependence on Russia’s raw materials, the mining exploitation has not been directly targeted by sanctions, allowing for ongoing investments and development.

The Russian government intends to guide and stimulate the development of the Arctic territory using tax cuts and incentives such as grants to fund infrastructure, driving plans for the economic development of the Arctic region.

Big groups such as Norilsk Nickel and Alrosa have a historic presence, and mines are a key component of the economic development of the northern region and new projects are being added. One of these is a plan to develop the Monchetundra deposit, which contains significant reserves of cobalt, copper, nickel, platinum and gold. The UK-based Eurasia Mining and Russian state-owned firm Rosgeologiya have formed a partnership to exploit these deposits.

Another significant gold-mining site in Russia is the Kyuchus deposit, located near Tiksi, a port on the Laptev Sea. Beloye Zoloto (“White Gold”) holds the licence to the deposit, which contains more than 175 tonnes of gold. The plan is to provide energy from Rostatom’s new line of small modular nuclear power reactors with a capacity of 35 MW that are helping to open up far flung deposits with their localised power supplies.

Another new project is between Russia’s Rustitan Group and Chinese state-owned China Communication and Construction Company, which have signed an agreement to develop a titanium deposit in the Republic of Komi, a former Gulag nexus.

Rosatom is playing a key role in opening up the interior with its modular reactors as well as floating nuclear power stations. But the state-owned nuclear power monopolist has also been expanding in the mining business in the last two years through its subsidiary AtomRedMetZoloto (ARMZ).

Historically, ARMZ has focused on extraction at uranium deposits to provide itself with fuel. But more recently ARMZ is diversifying and mining other minerals. First, the Pavlovskoye deposit (lead and zinc) on the Novaya Zemlya archipelago is under development, representing an investment of RUB72bn (€1.3bn). Secondly, in association with the Norilsk Nickel group, ARMZ plans to exploit the Kolmozerskoye deposit (Murmansk Oblast), the country’s largest lithium reserve (accounting for 18.5% of national reserves). Rosatom and Nornickel have established the joint venture Polar Lithium to exploit these deposits. Of the country’s 12 proven lithium reserves, 55% are located in Murmansk Oblast. Eventually Rosatom aims to supply 10% of the global lithium market.

Weaponising minerals

“For Western powers, the fact that Russia is so deeply integrated into the global metals and minerals market makes it difficult to adopt sanctions against this segment as a whole, when the world economy has already been shaken by the Covid-19 pandemic since 2020,” says IFRI.

Minerals could turn out to be a potent weapon in Russia’s clash with the West. Accounting for only a small part of Russia’s export earnings, curbing exports will have little effect on Russia’s budget, but would prove devastating for a variety of industries around the globe ranging from the automotive and plane-building to agriculture.

There have been some sanctions on the sector, but they have focused on individuals, while their companies have been left largely untouched.

The UK has placed individual sanctions on several extraction oligarchs including: Roman Abramovich (shareholder of steel mill Evraz and aluminium producer Rusal), Oleg Deripaska (chairman of Rusal), Andrey Guryev (founder and CEO of fertiliser makers PhosAgro), Sergey Ivanov (CEO of Alrosa) and Vladimir Potanin (CEO of Norilsk Nickel).

Amongst the Americans involved in Russian minerals, Boeing suspended its partnership contract with Russian titanium producer VSMPO AVISMA, a subsidiary of state-owned group Rostec, which has been subject to financial and trade sanctions since 2014. But replacing Russian titanium, essential for making planes, means that European group Airbus has continued to receive its titanium supplies from subsidiaries of Rostec.

In order to maintain supplies, but at the same time punish Russia, the UK also increased its customs tariffs for imports of platinum and palladium from Russia and Belarus as part of its sanctions regime.

Diamond miner Alrosa has proved particularly vexing. Belgium has lobbied against sanctions on the export of Russian diamonds, as Antwerp’s local economy is so dependent on trading prime diamonds. The US and the EU have failed to agree on a common line: while the Office of Foreign Assets Control (OFAC) of the US Treasury Department placed the diamond giant on its sanctions list, the EU decided not to impose similar sanctions under pressure from Belgium.

Likewise, Russia’s deep integration into the global metals market means that the London Metal Exchange (LME) also eventually decided not to prohibit trading and storing metals originating from Russia within its system, fearing a market meltdown if it did.

But the most potent weapons in Russia’s arsenal are the minerals connected to the EV industry.

“Palladium, in particular, of which 38% of global production takes place in Russia, could represent a powerful lever: an embargo or a slowdown in export procedures would have a minimal financial impact for the Russian state – palladium accounts for just 0.43% of domestic GDP – but would cause a major shock to the Western car industry and a global market upset,” says IFRI. “Likewise, the exponential growth in demand for nickel – an essential component in the manufacture of certain models of electric vehicle batteries – gives Russia an additional advantage in its economic war against the West.”

Africa rising

Even without explicit sanctions, Europe has begun to wean itself off imports of Russian minerals and the US is already almost totally self-sufficient in everything bar uranium and specialist metals like palladium and titanium for the meantime.

Africa is almost as rich in minerals as Russia, and is also one of the fastest growing markets. Both Russia and China has been actively investing in African mining operations for both commercial and geopolitical reasons. Raw materials have always been a major Kremlin foreign policy tool. And since sanctions were imposed on Russia, minerals have also become an extremely useful way of dodging the financial sanctions.

“The exploitation of African mineral resources is a means of bypassing the sanctions regime, particularly Russia’s isolation from the international banking system. Precious commodities such as gold and diamonds are useful for escaping banking sanctions because they can be sold and traded without oversight or restrictions,” says IFRI.

Russia’s mining companies, Alrosa and Rusal, have established a strong presence in African countries such as Angola, Zimbabwe, Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). In addition to their economic interests, Russia has geopolitical ambitions in Africa that are facilitated by the exploitation of mineral deposits.

As part of the effort to strengthen mineral ties with African countries, the Kremlin has also made use of that other plank of its foreign policy power: the military.

The Wagner group, led by Yevgeny Prigozhin, has been active in certain African countries, offering security services in exchange for “lucrative mining contracts.” In some cases, African governments have paid for Wagner’s help with mining deals.

“For instance, in the Central African Republic, Wagner’s links with mining companies M Finans and Lobaye Invest reveal the nature of these ties. These firms are allegedly controlled by Prigozhin, and licences to exploit diamond and gold deposits were awarded to a Russian company believed to be close to the founder of Wagner,” says IFRI.

The Wagner group has sought to amend the local mining code to establish a monopoly on precious commodities such as gold and diamonds in the CAR.

Wagner is also acting in Sudan. In 2017, Prigozhin’s group obtained significant mining concessions for gold and diamond deposits in what is the world’s third-largest producer of gold. Russia’s ties with Khartoum have deepened in recent years, and Russian mercenaries are helping Sudan’s security forces to repress pro-democracy movements. Despite US pressure, Russia is still pursuing its plan to build a naval base in Port Sudan on the Red Sea.

The upcoming Russia-Africa economic forum to be held in St Petersburg in July will serve as a platform for the development of Russian mining activities in Africa and almost all the heads of state from the 54 African countries are expected to attend.

Key commodities

“Certain [Russian] commodities that are integrated into the global economy appear to be difficult to substitute. This is the case with diamonds, phosphate and nickel. These three segments represent the complexity of the mining sector, as well as the associated industrial and geoeconomic issues at play. Whether in relation to the high-tech sector for diamonds, agriculture for phosphate or the energy transition for nickel, Moscow has numerous assets that it is mobilising with a view to maintaining its sectorial competitiveness for each segment concerned,“ says IFRI.

Russia has a wide variety of important minerals at its disposal to influence the rest of the world, making it harder to sanction.

Coal: Global coal consumption has reached an all-time high since the Industrial Revolution, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). In 2022, consumption of coal soared to a record 8,025mn tonnes and is expected to remain stable until 2025 at 8,038mn tonnes. Despite its negative impact on the environment, the Russian government plans to boost its coal industry through a programme that extends up to 2035.

To boost the industry, the Russian government has laid out plans to invest in the modernisation of industrial infrastructure in the Kuzbass basin, located in Kemerovo Oblast. Additionally, new deposits in the Siberian Arctic are being explored for exploitation. Russia’s share of international coal trade has grown from 9% to 15% in the past decade, with the Asia-Pacific region being the primary market.

While Russian researchers predict annual coal production to reach between 330mn tonnes and 365mn tonnes by 2035, the government’s most optimistic scenario envisages production of up to 670mn tonnes. However, this seems unrealistic as production capacity is limited, says IFRI. Coal production has risen gradually from 258mn tonnes in 2000 to 439mn tonnes in 2019, but the global health crisis caused a decline in output to 398mn tonnes in 2020.

Diamonds: Natural diamonds are often associated with the glamorous world of jewellery. However, these precious stones possess unique characteristics that make them a valuable material in the industrial sector for grinding and mining in particular.

“Moscow has both economic and political dominance over [the diamond] segment, with the conditions of the diamond market evolving rapidly,” says IFRI.

Russia is a major player in the global diamond market, with the Republic of Sakha (Yakutia) accounting for 25% of global diamond production and 80% of Russia’s national diamond output. The Alrosa group, which is controlled by the federal state (33%) and the regional government and municipal districts of Yakutia (33%), operates 24 diamond deposits in the country.

Unfortunately, the uncontrolled exploitation of diamond deposits in Yakutia has led to a disastrous environmental situation. Soil and waterways near the mining sites have been severely contaminated as a Soviet-era legacy.

Alrosa sells its diamonds on the international market through the global diamond syndicate, the Central Selling Organisation (CSO), established by South African company De Beers. The co-operation between De Beers and Russia began in 1959 with the launch of mining activities in Yakutia. Alrosa is the world’s leading supplier of natural diamonds, producing between 35mn and 40mn carats a year (equivalent to between 7 and 8 tonnes).

Russia also has considerable political clout as a key member of the Kimberley Process, an international trade forum established in 2000 to certify stones and stamp out the sale of “blood diamonds” used to financial civil wars in Africa, giving it another lever over the continent. For example, during Moscow’s chairmanship of the forum in 2021, diamond mines in the Central African Republic were allowed to continue to operate despite the blood tussle with pro-democracy forces there.

Even after the war in Ukraine started, Russia still leads two of the six Kimberley Process working groups. However, the definition of “conflict diamonds” has failed to expand to include the use of private or government-backed paramilitary forces.

To meet the needs of the high-tech industry, the production of synthetic diamonds is rapidly growing, where Russia also plays a dominate role. China, Japan and India are emerging as top competitors in the field. Synthetic diamonds represent about one quarter of Alrosa’s annual production, with its market share expected to grow by 9% annually until 2028. 70% of synthetic diamond production is used in industry, and another 13% is used for the production of semiconductors, sensors, laser systems and optical fibres.

To maintain its leading position in the synthetic diamond market, Russian company Synthesis Technology (Syntechno) has opened a factory for the production of synthetic diamonds in Pskov Oblast and intends to expand it.

Fertilisers: Russia is the biggest fertiliser maker in the world and as such can affect agricultural production throughout Europe and Africa.

“In Russia, the fertiliser sector is without doubt the one with the most complete and accomplished value chain, from the extraction phase right through to distribution on the market. Four groups dominate the country’s fertiliser segment: Acron, EuroChem, PhosAgro and Uralchem,” says IFRI. “Although Russia does not dominate the fertiliser sector, it is still a key actor due to the global economy’s heavy dependence on an intensive farming model. In fact, Russian industrial groups, which dominate the value chain in this sector, constitute an indispensable link in the planet’s agricultural system.”

Fertilisers are a critical component in the global food supply chain. In Russia, fertilisers are structured around the Russian Association of Fertiliser Producers (RAFP), which was founded in 2008 and reports directly to the Ministry of Industry and Trade (Minpromtorg). Currently, 100 Russian fertilisers account for 20% of the global market, equivalent to $12.5bn.

PhosAgro, established in 2001, is Europe’s leading supplier of phosphate-based fertilisers. The company is vertically integrated and carries out its extractive activities in Kirovsk, Murmansk Oblast, where six deposits are currently being exploited. This site is the world’s biggest in terms of production of highly concentrated phosphate rock, with an estimated lifespan of 60 years.

PhosAgro is the primary distributor of fertilisers to Russian farmers, selling 3.54mn tonnes in 2020. In other words, 30% of its production is destined for the domestic market. While the company has distribution points worldwide, it plans to improve its distribution network throughout the country, with a particular focus on the development of liquid mineral fertilisers, which are becoming essential in regions regularly exposed to drought.

Due to the threat of sanctions, some CEOs have stepped down or sold their shares. For example, oligarch Dmitry Mazepin resigned as CEO of Uralchem and reduced his shareholding to 48% to make himself a minority shareholder in the hope of avoiding sanctions.

The prospect of a reduction in fertiliser supplies for the global farming sector could have a devastating effect on harvests in 2023, says IFRI. Reduced fertiliser usage would result in a proportional drop in global agricultural yields, driving up inflation again and possibly causing famines in markets like Africa. Farming powers such as Brazil, one of the world’s leading exporters of maize, soya, sugar and coffee, are continuing to trade with Russia and replenish their fertiliser stocks, while bypassing banking and logistics restrictions, as part of the emerging “BRICS bloc,” a growing geopolitical co-operation between the leading emerging markets of the world.

As with metal, Western countries have been hesitant to directly target Russian fertilisers with sanctions, recognising their importance to the global food supply chain. As such, companies such as PhosAgro will continue to play an important role in global agriculture, with a focus on sustainable and innovative approaches to fertiliser distribution and usage. Again, the West has limited itself to sanctioning the owners of the large companies, but even there several oligarchs have been exempted.

Nickel: In May 2020, the spillage of 21,000 tonnes of diesel oil into the Ambarnaya river, in the Siberian Arctic, was declared a federal emergency and one of the worst environmental disasters in Russia’s history. The accident happened following the failure of a storage tank and put the spotlight on its owner, the mining group Norilsk Nickel.

In response, Potanin, the leading shareholder and CEO of Nornickel, decided to initiate a profound transformation of the group’s environmental policy. “This evolution is taking place in a context of transformation of the global nickel market. The market is being upended by the policy of decarbonisation, which calls for the implementation of a transition based on renewable energies and the electrification of transport,” says IFRI.

Nickel is a vital component in the production of sustainable energy and lithium-ion batteries for EVs. With demand for these vehicles anticipated to soar over the coming years, it is predicted that the need for nickel ore will increase by up to 100% by 2050 compared to current levels, reports IFRI.

Major EV makers are getting ready. Carmaker Tesla has signed commercial agreements with non-Russian partners to secure non-Russian supplies of nickel. In contrast, Norilsk Nickel is targeting growth of between 25% and 35% in its nickel output by 2030 compared to 2017 and intends to sell to Asia, not the West.

Norilsk Nickel is currently the world’s leading producer of nickel, accounting for 17% of the global total production volume. Despite sanctions pressure, the company has begun to modernise its industrial equipment and launched a major ESG-driven clean up.

The company has an ambitious plan to reduce its sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions as part of its modernisation project and has already closed down several of the worst offending plants on the Kola peninsula. Its flagship Norilsk Metallurgical Complex, one of the largest emitters of SO2, makes the Norilsk region one of the most polluted in the world. The industrial renovation project aims to reduce SO2 emissions by 90% and concerns the entire polar division, covering both the Norilsk region and the Kola peninsula in the Arctic. The closure of the foundry complex in Nikel, a border town close to Norway, has already led to a reduction of 78% in SO2 emissions in 2021 compared to the previous year.

The need for sustainable development and adherence to the UN SDGs and ESG criteria have become a guiding principle for many investments. However, Norilsk Nickel continues to receive criticism from NGOs, particularly those associated with the indigenous populations of the region, who say the company could do more.

“The railway network suffers from a lack of competitiveness.”

What on earth does the author mean by this? Does he think that two railway lines owned by different companies, running side by side, would improve things? This is a ridiculous notion. Railway systems must be monopolies. The degradation of British Rail into a number of private companies, which sue each other for poor performance, has devastated a once-great rail system. Fares are vastly more expensive, and infrastructure investment has declined. And the same thing is happening now to Deutsche Bahn. “Competition and privatization” are mantras of the European Commission. One hopes Russia (and the other European counties) will not follow suit.