By Dmitri Lascaris, Website, 4/18/23

Those of us living in the West are shown the Ukraine war almost entirely from the Ukrainian perspective.

Moreover, what we see is heavily filtered by media personalities whose bias is overwhelmingly pro-NATO and pro-Ukraine.

Although it’s unquestionably important that we have unfettered access to the Ukrainian perspective, we cannot understand the causes and consequences of this (or any) war by confining ourselves to the perspective of only one party to the conflict. This is particularly true when the intermediaries who communicate that party’s perspective to us have a long and sordid record of lying to us about war.

As I’ve stated many times over the past year, the Western mainstream discourse about this existentially dangerous conflict is wildly imbalanced. Therefore, a core purpose of my coming to Russia at this time is to contribute in any way I can to generating a more balanced discourse about this war.

With that overarching objective in mind, I decided last week to visit a refugee centre staffed by Russian volunteers and situated in Russian-controlled territory.

Full Disclosure

In anticipation of facing the standard accusation that I’m acting as a mouthpiece of Russia’s government, I offer to you full disclosure of the background of this journey.

First, no one invited me to travel to a refugee centre under Russian control, or to visit the Crimean border. I made this decision on my own initiative, just as I decided on my own initiative to come to Crimea.

Second, for purposes of visiting that refugee centre, I hired a driver by the name of Mikhail and a translator by the name of Tanya. Both of them reside in Crimea. Tanya has lived here her entire life. Mikhail has lived here for about nine years and came to Crimea from Moscow. He told me that he came to Crimea from Moscow because Moscow is too big for his liking. Tanya and Mikhail were recommended to me by Regis Tremblay, an American documentary film-maker who currently lives in Crimea. I learned of Regis last year, by chance, when I stumbled upon some videos he had posted on YouTube.

My understanding is that Tanya and Mikhail derive an income from the tourism trade. Tanya is also a professional translator and Mikhail is also a yoga instructor. I have no reason to believe that either of them is an employee or agent of the Russian government or any governmental authority. If I had reason to believe that they act for any government or governmental authority, I would not have hired them.

Third, I compensated both Tanya and Mikhail out of my own pocket. No one is reimbursing me for these expenses and, if any one offered to me reimbursement, I would refuse it. Regis accompanied us on this journey. He filmed my interview of Nicolai, a humanitarian worker at the refugee centre. (The full video of my interview of Nicolai appears toward the end of this article.) Regis did not ask to be compensated for this service, nor will I compensate him. I have agreed with Regis that he is free to use all footage he shot at the refugee centre for his own documentary purposes.

Finally, no one has compensated me, or offered to compensate me, for visiting the refugee centre or for writing this article. If anyone offered to compensate me for these services, I would refuse that offer.

Some historical context

The history of Crimea is extraordinarily complex. A comprehensive review of that history is beyond the scope of one article. Below, I offer what I consider to be a few of the more salient historical facts. Hopefully, these facts will give you a sense of the ethnic, cultural, linguistic and political complexity of this region.

The recorded history of the Crimean Peninsula begins around the 5th century BCE when several Greek colonies were established along its coast, the most important of which was Chersonesos near modern day Sevastopol. The south coast remained in Greek culture for almost two thousand years, including under Roman successor states and the Byzantine Empire.

In the 1400s, the Crimean Peninsula came under Ottoman rule. A major source of commerce during this period was frequent raids into Russia for slaves.

In 1774, the forces of Catherine the Great defeated the Ottoman Empire. Catherine the Great’s incorporation of Crimea into the Russian Empire increased Russia’s power in the Black Sea area.

During the Russian Civil War, Crimea changed hands many times. The anti-Bolshevik White Army made their last stand in Crimea in 1920. In 1921, the Crimean ASSR was created as an autonomous republic of the Russian SFSR.

During World War II, Crimea was occupied by Germany until 1944. The ASSR was downgraded to an oblast within the Russian SFSR in 1945 following the deportation of the Crimean Tatars by the Soviet government.

In 1954, the Soviet government, led by Nikita Khrushchev, transferred Crimea from the Russian Soviet Federation of Socialist Republics (RSFSR) to the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic (UkrSSR). At the time, about 75% of Crimea’s population was ethnically Russian.

Historians have struggled to understand why Khrushchev’s government effected the transfer. According to the Wilson Center, Khrushchev believed that adding Crimea’s ethnically Russian population to the UkrSSR would strengthen Moscow’s control over Ukraine.

As the Center for Strategic and International Studies explained in 2014, control of Crimea ensures Russia’s access to a natural, warm-water port having extensive infrastructure (Sevastopol) and “provides Russia with important strategic defence capabilities.”

As of 2014, when Crimea merged with Russia, approximately 68% of Crimea’s population was ethnically Russian, while only 16% was ethnically Ukrainian. In a referendum held that year, 97% of voters reportedly supported Crimea’s reunification with Russia. The turnout for the vote was reportedly 83%. Remarkably, control of Crimea passed from Kyiv to Moscow without any blood being shed.

In the week that I have spent in Crimea, I have traveled to Yalta, Sevastopol, Simferopol and the Crimean border with Kherson. I have yet to meet a single person who expressed a desire to see Crimea returned to Ukrainian control. On the other hand, I have spoken to many people who are adamant that Crimea is part of Russia.

From Simferopol to the Crimean Border

On Easter weekend, Regis, Tanya, Mikhail and I travelled by car from Simferopol, the capital of Crimea, to the Crimean Border Volunteer Camp (CBVC), a refugee centre situated steps away from Crimea’s northern border. The CBVC lies about fifty kilometres from the nearest point of the front line in the Ukraine war. The CBVC is operated by Organized Volunteers of Russia, an NGO founded by activists from St. Petersburg.

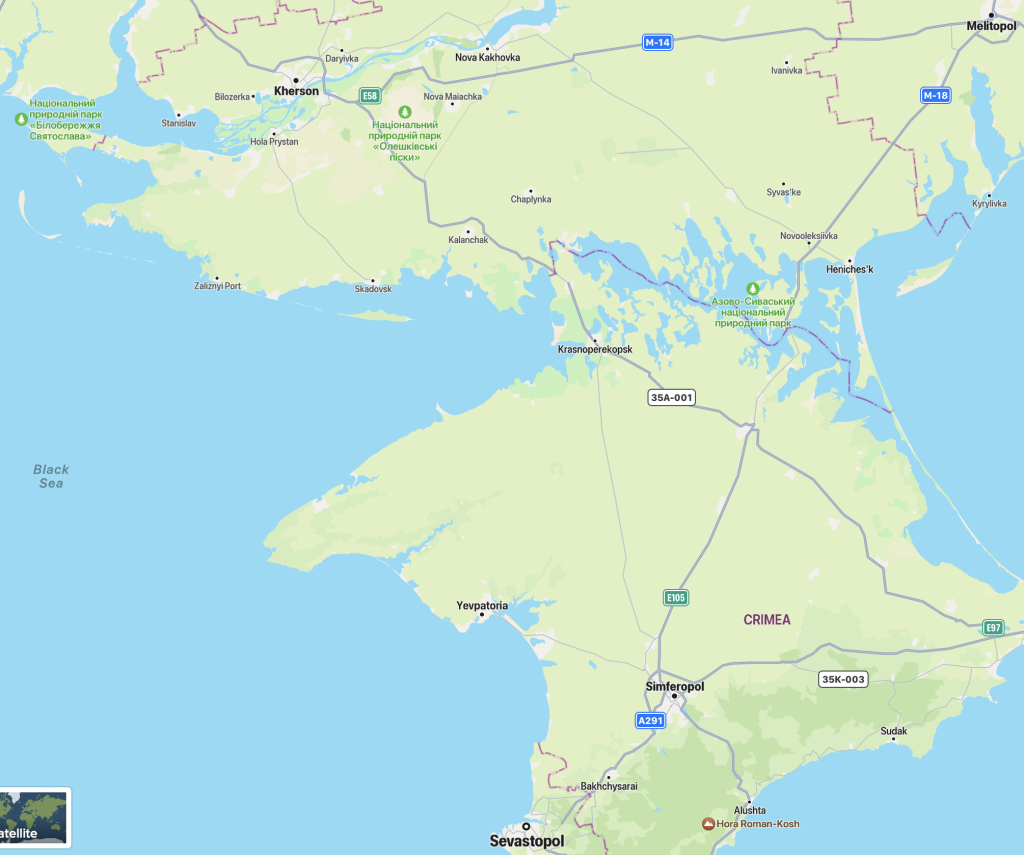

On the northern side of the Crimean border lies Kherson, one of the four oblasts being contested by Ukrainian and Russian forces. Russian forces currently control the entire territory of Kherson lying to the east of the Dnieper River. This constitutes approximately 60 percent of the Kherson oblast.

As we drove out of Simferopol, I was struck by the amount of development going on. I repeatedly saw high-rise apartment buildings that were either brand new or that were under construction. At one point, we passed by a newly constructed hospital, which Tanya described as a state-of-the-art medical facility.

After the merger of Crimea with the Russian Federation, Ukraine’s coup regime and far-right Ukrainian groups targeted Crimea’s residents with collective punishment.

After the 2014 referendum, Ukrainian banks ceased doing business with many residents of Crimea. This resulted in some Crimeans losing funds previously held in these banks. Tanya tells me that she herself lost the equivalent of about US$10,000 when her Kyiv-based bank refused to deal with her any further. She also said that she knows of some businesses operating in Crimea’s tourism industry that lost as much as US$100,000 in bank deposits.

In 2014, Ukraine cut off the fresh water supply to Crimea by damming a canal that had supplied 85% of the arid peninsula’s needs before Crimea merged with Russia.

In 2022, after seizing control of much of the Kherson region, Russian troops destroyed the concrete dam that Ukraine had built in 2014. This has relieved much of the water stress that Crimea experienced during the prior eight years. As we were driving through Simferopol, we passed by a massive reservoir that had dried up after Ukraine’s construction of that dam. As this video shows, that reservoir is now essentially full:

In 2015, Ukrainian ultra-right extremists destroyed electrical infrastructure that was used to supply electricity to Crimea and that was situated in Kherson, which was then under Ukrainian control. According to Tanya, this resulted in severe disruptions to Crimea’s economy, but the government of the Russian Federation managed to restore Crimea’s electricity supply within about eight months.

As we sped away from the Simferopol reservoir and toward Crimea’s northern border, we saw more and more Russian military vehicles.

Can Ukraine recover Crimea?

Until I came to Crimea, I had not understood that any ground attack by Ukrainian forces against the Crimean peninsula would have to pass through very narrow corridors of land flanked on either side by bodies of water. There are two such corridors.

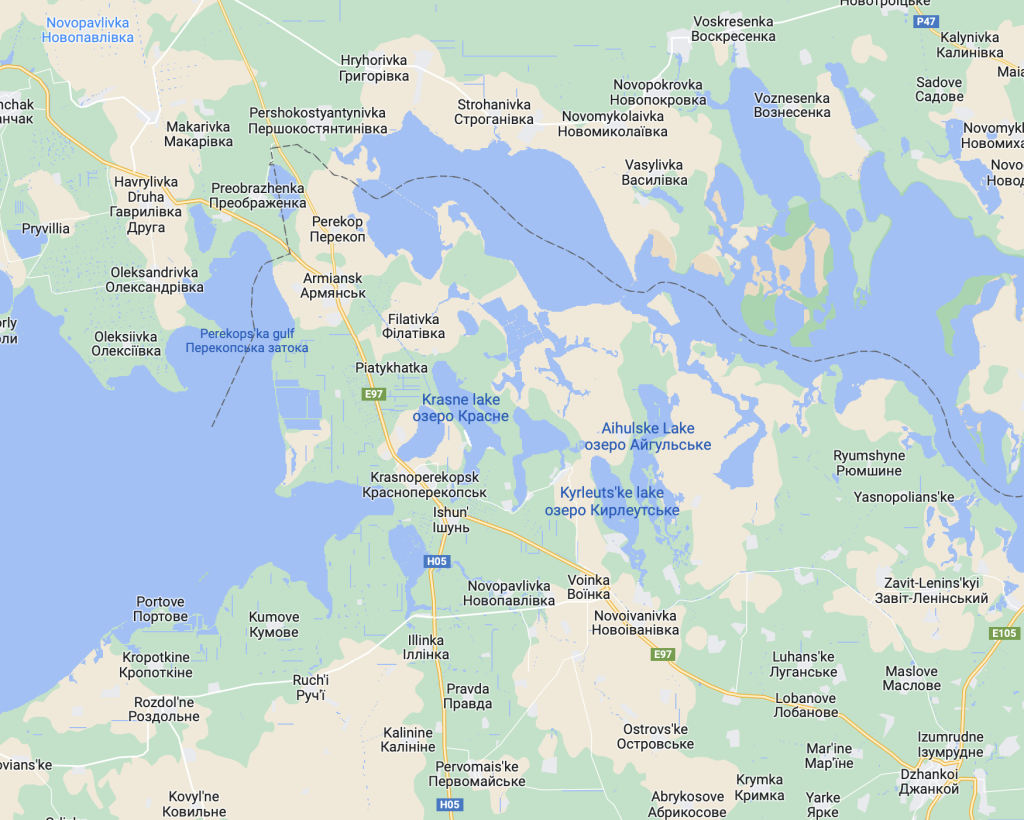

One is the strip of land on which the town of Armiansk is situated. That land corridor appears in the northwestern (upper left-hand) quadrant of the map below:

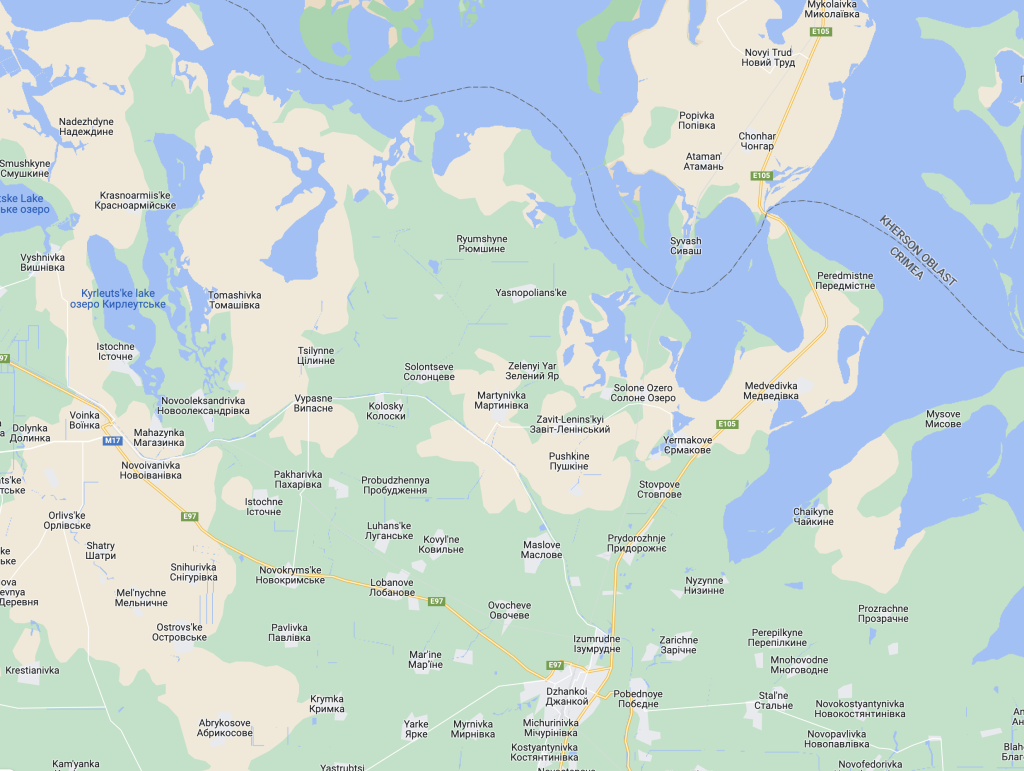

The second corridor connecting Kheron to Crimea lies to the northeast of Dzhankoi, on the E105 roadway. It is the narrow strip of land on which Peredmistne is situated and appears in the northeastern (upper right-hand) quadrant of this map.

The CBVC is situated in this second corridor, to the north of Peredmistne, and just south of the Crimea-Kherson border.

As we drove northward on the E105 through that narrow corridor, we saw multiple lines of trench-works and concrete, anti-tank obstacles on both sides of highway.

I do not profess to be a military expert, but I cannot imagine how Ukrainian forces could pierce this narrow corridor of heavily fortified territory .

Here, there is precious little room for attacking forces to manoeuvre. Moreover, Russian forces have established multiple defence lines. The land is flat and open, with virtually no tree cover. Also, it may well be that Russian forces have heavily mined some or all of the open fields in this area. Therefore, even if Ukrainian forces could reach the Crimea-Kherson border (which is highly doubtful), their prospects of penetrating into the Crimean peninsula in large numbers would be minuscule to non-existent.

In light of these realities, it is irresponsible for Zelensky’s government to define ‘victory’ for Ukraine to include the recovery of Crimea and, even worse, to issue regular assurances to the Ukrainian people that the recapture of Crimea is imminent. It is one thing to raise the morale of your people. It is quite another to deceive them about what is realistically possible. Even U.S. officials have publicly dismissed the claim that Ukraine can recover Crimea militarily.

By setting the bar of victory impossibly high, Zelensky is dooming the Ukrainian people to a prolonged war that can only end in defeat. Moreover, if by some miracle Ukrainian forces could achieve ‘victory’ as Zelensky has defined it, that ‘victory’ would likely bring perpetual instability to Ukraine, because a majority of Crimea’s residents are fiercely opposed to Ukrainian rule.

The Crimean Border Volunteer Camp

As we neared the CBVC and the Crimean border, the E105 became congested with Russian military vehicles.

Upon arriving at the CBVC, we discovered it to be a small facility. It is too close to the war zone to constitute a sanctuary for refugees. The purpose of the facility is to provide temporary relief from the war and to organize incoming refugees for rapid transfer to safer facilities further from the war zone (for example, facilities situated in Simferopol or Sebastopol).

When we visited the camp, there were only three refugees there: two young parents and their seven-year old daughter. They did not wish to be interviewed on camera. We learned that the family’s goal was to reach Poland, which has provided extensive military and economic support to Ukraine and has received a large number of Ukrainian refugees. The family had decided to travel to Poland through Crimea because they feared that, if they had attempted to enter Poland directly from Ukraine, Ukrainian forces would have apprehended the father at the border and would have forced him to serve in the Ukrainian military.

We spoke to six workers at CBVC. All of them were volunteers from diverse parts of the Russian Federation. They advised us that they do not discriminate between refugees who wish to travel to Russia and those who wish to travel to other European states, even if the governments of those states are hostile to Russia. The camp workers explained that, although most refugees they encounter wish to transit to Russia, they have encountered numerous male refugees who wish to transit into Western Europe through Crimea because they are afraid of being apprehended by Ukrainian forces at the Poland-Ukraine border.

In Ukraine, the number of military-aged men who are trying to avoid conscription appears to be significant.

I spoke for about thirty minutes with one of the CBVC volunteers. His name is Nicolai and he hails from Siberia. In 2022, before coming to CBVC, Nicolai volunteered as a humanitarian worker in Donetsk. There, he witnessed Ukrainian shelling of civilian areas, including a hospital. In my interview of Nicolai, he and I discussed his experiences at CBVC and Donetsk, and also discussed the International Criminal Court’s allegation that Russia’s government is separating Ukrainian children from their parents – an accusation which Nicolai described as “fake news”.

This is the video of my unedited discussion with Nicolai:

After I interviewed Nicolai, and as our team was loading our gear into Mikhail’s vehicle in preparation for our departure from the camp, Nicolai ran up to me and handed me an arm patch as a parting gift. His gift (pictured below) came as a pleasant surprise to me, because as much as I admire Che Guevara, I never mentioned Che to Nicolai.