By Natylie Baldwin, Covert Action Magazine, 5/5/23

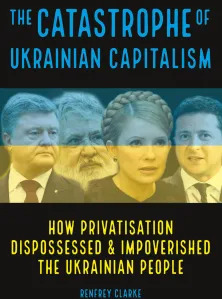

Renfrey Clarke is an Australian journalist. Throughout the 1990s he reported from Moscow for Green Left Weekly of Sydney. This past year, he published The Catastrophe of Ukrainian Capitalism: How Privatisation Dispossessed & Impoverished the Ukrainian People with Resistance Books.

In April, I had an email exchange with Clarke. Below is the transcript.

Natylie Baldwin: You point out in the beginning of your book that Ukraine’s economy had significantly declined by 2018 from its position at the end of the Soviet era in 1990. Can you explain what Ukraine’s prospects looked like in 1990? And what did they look like just prior to Russia’s invasion?

Renfrey Clarke: In researching this book I found a 1992 Deutsche Bank study arguing that, of all the countries into which the USSR had just been divided, it was Ukraine that had the best prospects for success. To most Western observers at the time, that would have seemed indisputable.

Ukraine had been one of the most industrially developed parts of the Soviet Union. It was among the key centres of Soviet metallurgy, of the space industry and of aircraft production. It had some of the world’s richest farmland, and its population was well-educated even by Western European standards.

Add in privatisation and the free market, the assumption went, and within a few years Ukraine would be an economic powerhouse, its population enjoying first-world levels of prosperity.

Fast-forward to 2021, the last year before Russia’s “Special Military Operation,” and the picture in Ukraine was fundamentally different. The country had been drastically de-developed, with large, advanced industries (aerospace, car manufacturing, shipbuilding) essentially shut down.

World Bank figures show that in constant dollars, Ukraine’s 2021 Gross Domestic Product was down from the 1990 level by 38 per cent. If we use the most charitable measure, per capita GDP at Purchasing Price Parity, the decline was still 21 per cent. That last figure compares with a corresponding increase for the world as a whole of 75 per cent.

To make some specific international comparisons, in 2021 the per capita GDP of Ukraine was roughly equal to the figures for Paraguay, Guatemala and Indonesia.

What went wrong? Western analysts have tended to focus on the effects of holdovers from the Soviet era, and in more recent times, on the impacts of Russian policies and actions. My book takes these factors up, but it’s obvious to me that much deeper issues are involved.

In my view, the ultimate reasons for Ukraine’s catastrophe lie in the capitalist system itself, and especially, in the economic roles and functions that the “centre” of the developed capitalist world imposes on the system’s less-developed periphery.

Quite simply, for Ukraine to take the “capitalist road” was the wrong choice.

NB: It seems as though Ukraine went through a process similar to that in Russia in the 1990s, when a group of oligarchs emerged to control much of the country’s wealth and assets. Can you describe how that process occurred?

RC: As a social layer, the oligarchy in both Ukraine and Russia has its origins in the Soviet society of the later perestroika period, from about 1988. In my view, the oligarchy arose from the fusion of three more or less distinct currents that by the final perestroika years had all managed to accumulate significant private capital hoards. These currents were senior executives of large state firms; well-placed state figures, including politicians, bureaucrats, judges, and prosecutors; and lastly, the criminal underworld, the mafia.

A 1988 Law on Cooperatives allowed individuals to form and run small private firms. Many structures of this kind, only nominally cooperatives, were promptly set up by top executives of large state enterprises, who used them to stow funds that had been bled off illicitly from enterprise finances. By the time Ukraine became independent in 1991, many senior figures in state firms were substantial private capitalists as well.

The new owners of capital needed politicians to make laws in their favour, and bureaucrats to make administrative decisions that were to their advantage. The capitalists also needed judges to rule in their favour when there were disputes, and prosecutors to turn a blind eye when, as happened routinely, the entrepreneurs functioned outside the law. To perform all these services, the politicians and officials charged bribes, which allowed them to amass their own capital and, in many cases, to found their own businesses.

Finally, there were the criminal networks that had always operated within Soviet society, but that now found their prospects multiplied. In the last years of the USSR, the rule of law became weak or non-existent. This created huge opportunities not just for theft and fraud, but also for criminal stand-over men. If you were a business operator and needed a contract enforced, the way you did it was by hiring a group of “young men with thick necks.”

To stay in business, private firms needed their “roof,” the protection racketeers who would defend them against rival shake-down artists—for an outsized share of the enterprise profits. At times the “roof” would be provided by the police themselves, for an appropriate payment.

This criminal activity produced nothing, and stifled productive investment. But it was enormously lucrative, and gave a start to more than a few post-Soviet business empires. The steel magnate Rinat Akhmetov, for many years Ukraine’s richest oligarch, was a miner’s son who began his career as a lieutenant to a Donetsk crime boss.

Within a few years from the late 1980s, the various streams of corrupt and criminal activity began merging into oligarchic clans centred on particular cities and economic sectors. When state enterprises began to be privatised in the 1990s, it was these clans that generally wound up with the assets.

I should say something about the business culture that arose from the last Soviet years, and that in Ukraine today remains sharply different from anything in the West. Few of the new business chiefs knew much about how capitalism was supposed to work, and the lessons in the business-school texts were mostly useless in any case.

The way you got rich was by paying bribes to tap into state revenues, or by cornering and liquidating value that had been created in the Soviet past. Asset ownership was exceedingly insecure—you never knew when you’d turn up at your office to find it full of the armed security guards of a business rival, who’d bribed a judge to permit a takeover. In these circumstances, productive investment was irrational behaviour…

Read full interview here.

This is a really interesting interview thank you. I think I remember someone talking about the shipbuilding industry so they moved to China instead.