By Stephen Bryen, Asia Times, 12/7/23

Pitching Congress with a proposal for more aid for Ukraine, US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin conjured up a threat from Russia.

Austin said that if Congress does not appropriate $61 billion in aid for Ukraine it is “very likely” US troops on the ground in Europe will be fighting Russia.

Republican senators – for various reasons, including especially a dispute over whether to tie the aid to US border security – walked out of the briefing after only twenty minutes.

The threat that Austin imagined is that Russia, after it finishes with Ukraine, will launch attacks in Europe. Objectively, though, there is no evidence that Russia threatens anyone in Europe.

That’s not to say there aren’t a lot of Russians who think their generals should be threatenng Europe. After all, Europe is providing massive military aid, intelligence and technical help to Ukraine in the war with Russia, along with training Ukrainian troops and helping Ukraine develop its war plans. Stocks of European weapons, meant for NATO defense, have been shipped to Kiev. Most of them won’t be replaced for decades, if ever.

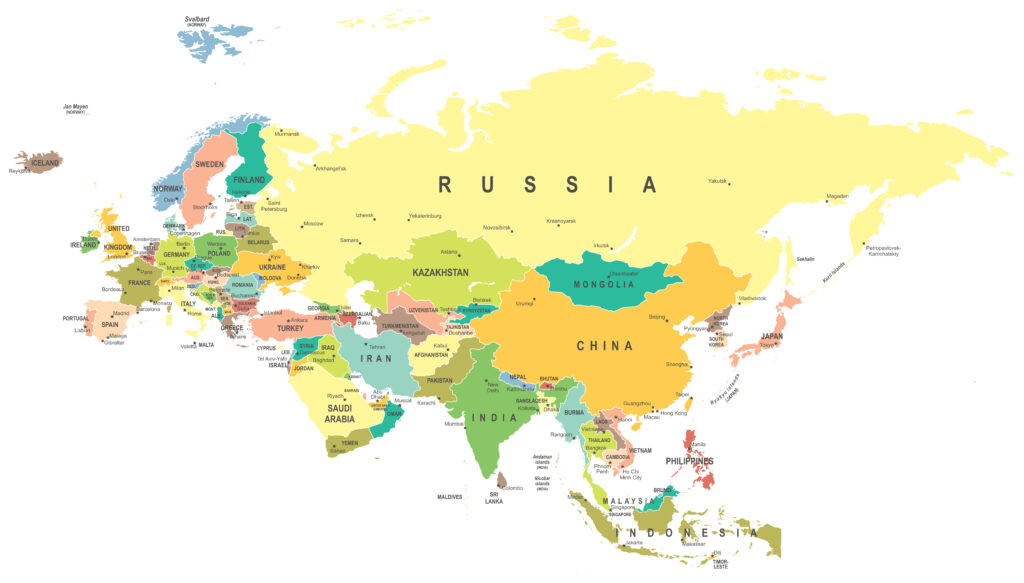

From Russia’s point of view the real land grabber is NATO. After all, despite Russia’s warnings and promises made to Russia that were blatantly violated, NATO expanded in the Balkans and in Eastern Europe. (The Russians were frequently assured, starting with a vow from former President Bill Clinton [it was the Bush I administration which first made the promise, not Clinton – NB], that NATO would not expand.)

Expansion has meant arming the new NATO members with top quality western weapons, building bases for NATO on their territories and threatening Russia directly.

One of the reasons Russia took over most of Eastern Europe at the end of World War II was to create a security buffer. That was not the only reason, of course; the Russians also were anxious to get hold of resources in these countries. One recalls that Russia suffered huge devastation and depopulation thanks to the Nazis and their allies.

None of this means Russia would not like to get back what it lost to NATO’s expansion after the collapse of the Soviet Union. And, yes, it is quite true that Russia’s “Special Military Operation” can be regarded as a land grab in Ukraine.

But there is little sign that Russia intends any expansion in Eastern Europe or the Baltic States and virtually no intelligence of any kind supporting the Austin invasion thesis. If there were any concrete intelligence you can safely bet the Biden administration would let Congress know (especially when it has its hands out for more money for the war).

There are three reasons for crediting the opposite hypothesis, namely that Russia has no intention of expanding outside of the Ukraine conflict area.

The first reason is behavioral. With NATO’s war stocks at an all time low, Russia could have taken advantage of this vulnerability and moved its forces against NATO targets – for example NATO operations in Poland or in the Balkans – but have not done so.

The Russians have exercised unprecedented restraint and even tolerated aggressive intelligence flights and NATO naval exercises in the Black Sea, an extraordinarily sensitive Russian security worry. The Black Sea is not only the back door to Ukraine, it is also a route to challenge Russia itself.

Russia even exercised restraint when Ukraine used drones to hit an airfield inside Russia where nuclear bombers are based. Two of these bombers were either damaged or destroyed. Such an attack needed intelligence support from NATO, primarily the US, and the Russians no doubt understood that quite well. Yet the Russians tolerated the attack to a degree and took no steps to widen the conflict.

There is some evidence that the attack on the Soltsy-2 airbase was launched by the Ukrainians from Estonia, as Ukrainian drones did not have the range to reach the airbase.

Other examples of Russian restraint include the sinking of Russia’s flagship Moskva with US help, multiple attempts to destroy the Kerch Strait bridge connecting Russia to Crimea and multiple attacks on Moscow, including an attempt to hit Putin’s Kremlin office in what Russia says was an attempt to assassinate Putin.

The second reason to view Russia as reluctant to expand the conflict is that doing so would be immensely costly. Russia has already learned just how expensive the Ukraine war is, even though it is finally winning the war after nearly two years of fighting. But a war in Europe would add US and European fighter aircraft and bombers to Russia’s misery – even if NATO ground forces would have significant problems, according to a RAND study.

The greatest cost for Russia is manpower and casualties from the war. Figuring out actual casualties is difficult, because the Ukrainians and Russians alike either don’t tell the truth or say nothing.

Yet the fact that Russia needs to step up its military recruiting – has even filled gaps with prisoners – says that the war has taken many lives. It also means that the war’s popularity in Russia may be threatened if the numbers of killed and wounded grow too high.

It is hard to believe Russia would crank up a bigger war, given the impact on manpower. Nor would the war keep the support of the Russian people, who know how to oppose a conflict when it starts to bite them at home. That’s what forced Russia to leave Afghanistan, starting the withdrawal in May 1988 and completing it in February 1989. (That wasn’t enough to save Gorbachev or prevent a coup attempt and it led to the disintegration of the USSR.

The third reason that speaks against Russia expanding the conflict is the unanticipated wild card of Western sanctions on Russia.

In effect, responding to Putin’s “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine, NATO and many other countries aligned with the United States or with the European Union imposed heavy sanctions on Russia. This drove Russia into the arms of China and forced Russia to rethink its future. Above all it meant a realignment of Russia’s resources, trade and monetary system away from Europe and the west.

This is a decisive new factor that changes the strategic roadmap for Russia. It directly undermines the argument that Russia has something to gain from any attack on Europe. The truth is that the Russians are less and less interested in Europe or the United States. One can safely say that the extra-legal Western sanctions were a major strategic blunder for NATO and its partners and friends, as well as for the EU.

Even if a peace deal is made with Ukraine and Europe and the US lifts sanctions on Russia, it is probably too late to recover from the damage done to any future ties. Russia won’t reject trade with the West, but it is likely to make business deals only on its own terms. It is unlikely Russia will again allow western companies to operate inside Russia, and the country will increasingly team with China for technology and weapons development. In short, the west filed for divorce and the Russians accepted the final decree.

The Austin argument is, for the above reasons, false and misleading.

When the Republicans walked out of the secret briefing staged for the Senate to try and sell them on supporting more money for Ukraine, many argued that the Biden administration’s arguments were stale and unconvincing. The Biden effort to intimidate the Senate simply didn’t work.

What will the Biden bunch come up with next?

Having spent seveeral years in EE during the Cold War, I disagree with some of your assertions: Russia and China have been joined at the hip since its earliest days and this alliance is not going to weaken any time soon.

“your”? NB didn’t write the article.

Natalie, maybe it would help if the old newspaper disclaimer boiler plate was posted below the banner; though I expect some will not take it at face value.

The views and opinions expressed [in each article/video] are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of [Natylie’s Place: Understanding Russia and/or Natylie Baldwin or the authors of other articles / videos appearing or linked to in this blog.]