Emphasis by bolding is mine. – Natylie

By Mark Galeotti, The Spectator, 2/29/24

Secret documents have been leaked that reveal Russian scenarios for war games involving simulated nuclear strikes. They shed light on Moscow’s military thinking and its nuclear planning in particular, but ultimately only reinforce one key factor: if nuclear weapons are ever used, it will be a wholly political move by Putin.

The impressive twenty-nine documents scooped by the Financial Times date back to the period of 2008 (when Vladimir Putin was technically just prime minister but still effectively in charge) to 2014 (after the sudden worsening in relations with the West following Ukraine’s Revolution of Dignity and the annexation of Crimea). Although this means that they are a little dated, they nonetheless chime with our understanding of Russian doctrine today. As a result, they give a useful sense not only of the circumstances in which Moscow might use nuclear weapons, but also the degree to which China — for all the mutual expressions of friendship — is still regarded as a potential threat by the Russian military.

They spell out a series of criteria for the use of tactical or non-strategic nuclear weapons (NSNW), with yields of “merely” Hiroshima-level, compared with the kind of larger warheads which could level whole cities. All of them, in keeping with the state nuclear policy adopted in 2020, allow for the first use of nuclear weapons as a response to a serious and material threat to the state. Quite what this means seems to range from a significant invasion onto Russian soil to the loss of 20 percent of the country’s nuclear missile submarines. Overall, their use is envisaged in situations where losses mean that Russians forces could “stop major enemy aggression” or a “critical situation for the state security of Russia.”

Although the nuclear threshold looks a little lower than we might have previously thought, we need to be cautious about drawing too concrete a set of conclusions from the war game scenarios — not least because of how old the plans are. It is essentially a given that major Russian exercises will include a simulated nuclear strike for training ground purposes. To this end, they may be massaged to ensure such an outcome.

Yet there are two specific sets of questions that the FT‘s scoop does raise. The first relates to Ukraine. Could, for example, a major Ukrainian incursion into territories Moscow claims to have annexed trigger a nuclear response? The honest answer is that — in theory — it could, as these are now considered Russians. However, we have to be clear that any use of NSNWs would be a political one: it will be Putin, not some doctrinal flow chart, that makes the decision.

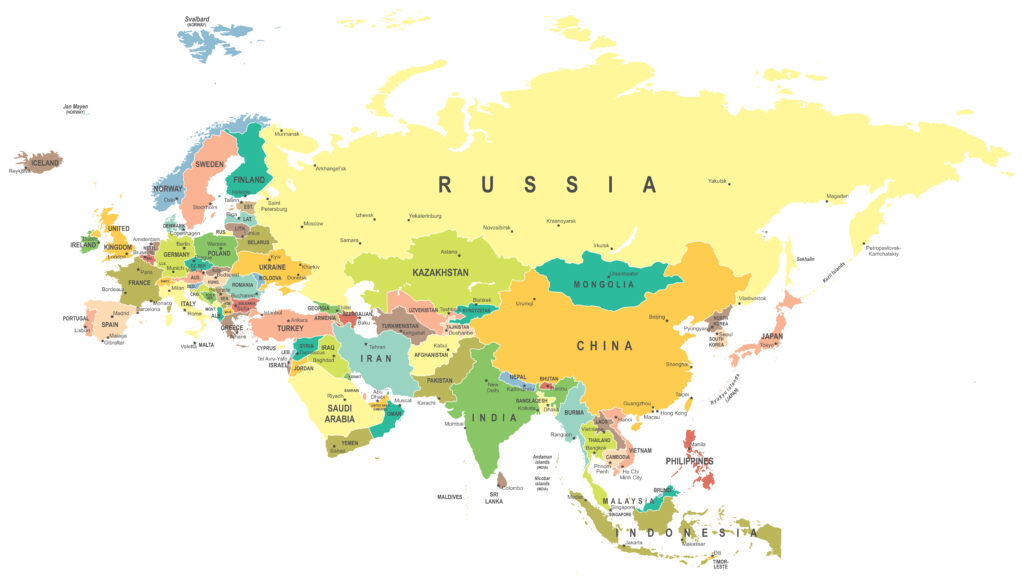

The documents are also interesting in the light they shed on Moscow’s relationship with Beijing. It should hardly be a surprise that the Russians wargame a clash with China. First of all, that’s what militaries do: prepare for even unlikely circumstances. Secondly, they’re not necessarily that unlikely, especially as nationalists in and outside the Chinese government periodically question the “unfair treaties” imposed on it in the nineteenth century, including the 1858 Treaty of Aigun and the 1860 Treaty of Peking. The latter, for example, saw some 390,000 square miles surrendered to Russia. Finally, there is a deep-seated suspicion of China within many of the security elite.

These documents post-date the 2001 Treaty of Good-Neighborliness, Friendship and Cooperation between China and Russia. In recent years, the Sino-Russian relationship has strengthened, but even so this is more than anything else because the enemy of my enemy is my strategic partner. It is a deeply pragmatic relationship, though. Beijing uses Moscow’s desperation for oil and gas sales to force down the price, while Russia’s security services have been stepping up their hunt for Chinese spies (and finding them).

There remain fears that Beijing might some day seek to take the under-populated Russian Far East for their land, their resources, and their historical importance. Even before the Ukraine invasion, there was no meaningful way Russia’s thinly-stretched forces in the Far Eastern Military District could stop such an attack, and thus it is no surprise that in the exercise notes, NSNWs are to be deployed “in the event the enemy deploys second-echelon units.”

Of course, both Moscow and Beijing have disputed the authenticity of these documents. However, they are not so much proof that Russian nuclear policy is more permissive than we had assumed but a reminder of the political aspect of their use. At sea, the Russians are more quickly willing to use NSNWs, not least because of the presumed lower risk for civilian “collateral damage.” On the eastern front, they are an essential equalizer when facing a more populous and rapidly-arming frenemy. In the west, they are an information weapon, a threat to brandish in the hope of scaring electorates into demanding Kyiv be forced into an ugly and unequal peace to avert potential escalation. The real unknown is quite what Putin thinks about using them in his Ukraine war, and that is not something we can find in any doctrines or documents, alas.