By James Carden, ACURA, 3/10/25

Ian Proud served in His Britannic Majesty’s Diplomatic Service from 1999 to 2023. He served as the Economic Counsellor at the British Embassy in Moscow from July 2014 to February 2019 and is the author of a trenchant memoir titled A Misfit in Moscow: How British diplomacy in Russia failed, 2014-2019.

He is also the author of the widely read Substack offering, The Peacemonger. His work also appears in Responsible Statecraft and The American Conservative, among other publications in the US and UK.

–James W. Carden

Carden: Ian, thanks for taking the time to talk. A lot’s been going on the past 72 hours. We had the Zelensky-Trump blow up, then you had Zelensky here with Keir Starmer, followed by the EU defense ministers meeting. Seems to me anyway, that if you’re not going to get Trump to go along with any of these plans for boots on the ground, then it is all for show…

Proud: So big picture: This is a strategic repositioning going on at the moment, where people are basically trying to get to an off-ramp out of Ukraine in a way that doesn’t make it appear that they have totally failed.

So there’s a lot of choreography going on at the moment, particularly on the UK side. I’ll come to that. But on Zelensky and Trump, I mean Zelensky is trying to create himself as some sort of icon. This is his thing, he wears T-shirts. I think it’s completely ridiculous.It stems from his entertainment background where he’s more focused on the image and the brand rather than the substance. I don’t really see him as a states-person. I see him as someone who hasn’t recognized that the Earth really isn’t flat, that things are changing, and that he actually needs to adapt.

I once compared him to Madonna, unfavorably. Madonna constantly changed her style and adapted. He hasn’t. And he’s saying what he’s been saying since the beginning of the war, and now he’s come up against President Trump. I mean, his first three to six months, I think he played quite well, apart from not signing in Istanbul. But since then, he’s been stuck and he’s increasingly centralized power upon himself, hasn’t listened to advice, and we’ve humored him. We’ve built him up as this icon of democracy. Which is amazing.

Carden: No one has reported on the fact that he has sanctioned and chargedhis predecessor [Petro] Poroshenko with high treason. Now, Biden, I guess, in his own way, tried to do that to Trump. And Trump called Zelensky a dictator, he was actually, in his Trumpian way, correct because he was supposed to hold elections a year ago.

Proud: He was, and people keep making these ridiculous comparisons to Winston Churchill which drives me nuts because during World War II, there was power sharing in the UK. Like, okay, elections were put on hold, but there was power sharing, all the main parties involved shared power. Churchill led it, but he had Labour ministers throughout—whereas Zelensky has centralized power upon himself.

Carden: You’re right. There was a specific effort at bipartisanship, as we call it. There’s none of that with Zelensky who has banned 11 opposition parties during his time in office. But he has this image….

Proud: As that narrative breaks down, they will say, well, when the war in Ukraine finishes, okay, maybe we’ll be able to have elections in six months. It will be so difficult. Well, we had elections less than two months after Victory over Europe Day following World War II, before indeed, the defeat of Japan.

Carden: One of the things that struck me is that Starmer seemed to be in quite a bit of political trouble up until very recently, but now he seems to be positioning himself as a kind of bridge between Europe and the US.

Proud: Essentially, since Lord Mandelson [now the UK’s Ambassador to the US] has arrived in Washington, the ambassador, and he’s not a Starmer ally, but he was chosen by Starmer for that job.

He wanted somebody who was from the Labour Party who would speak truth to power. Now, in the period running up to Lord Mandelson’s arrival in DC, Starmer was not really interested in foreign policy, and Lammy [David Lammy, the current UK foreign minister] is useless. They’ve been fed the policy by the deep state.

And in fairness to them, we’ve had nine foreign secretaries since 2014, and seven prime ministers. So what that means in practice, I think, for anybody in power, is that you are more reliant than normal on advice from the Blob.

And if you come in focused on the domestic agenda, fixing the country with the economic stuff, then you’re going to fall back on the Blob for easy answers on foreign policy. And what they did when they came in was just to, in the absence of ideas of their own, just adopt a more extreme version of what the Tories have been doing in Russia: Saying the same things, but tougher.

Tougher, which is total nonsense. And then Mandelson has come in and people are thinking about geo-economic issues right now, about trade wars and so on. And Mandelson, I think has said to Starmer, look, you’ve got two choices: You can show a point of difference with Trump and support Zelensky come what may and go against Trump, risk Trump’s ire and possible tariffs. Or you can actually align with the US and say, well, what we need more than anything else from our relationship is the acceleration of trade talks, which have been on hold really since Obama’s time, and an avoidance of tariffs. And we are going to throw Zelensky under the bus, but softly and over time in a way that it doesn’t look like we’re actually throwing them under the bus.

Carden: Maybe Trump, in a way, is doing Starmer a favor, since no one’s going to notice because Trump has just thrown him out the window in such a public fashion….

Proud: That’s true. Although at the same time, the Zelensky brand is much more powerful here than it is in the US. And so ditching Zelensky is not as easy a job here as it is in America.

Public opinion is pretty squarely behind, really, because the mainstream media just are completely aligned. All the political parties say exactly the same things. This is almost worse than Russia in terms of the avalanche of propaganda that we are fed.

Carden: That’s quite shocking though I did have a sense that was true, which is why I’m here. But one of the things I learned through my discussions this week was something that I was completely unaware of, which are “D notices” [they are officially called Defense and Security Media Advisory Notices] which are apparently warnings issued by the government to media organizations seen to be deviating from government policy.

Proud: I mean, this actually goes back to the Iraq war in 2003, and to 9/11, when Labour, much like Starmer’s doing now with Trump, wanted to align with George W. Bush. And it’s almost a repeat of what happened in 2001-2003, we wanted to be America’s best friend at a pivotal time in history. And Alistair Campbell famously sexed up the intelligence dossier to justify Britain’s involvement in the Second Iraq War.

But the point is that from that time, Number 10 started to exert a cast iron grip on the media narrative. And on one hand, they opened their doors to the media as never before for ‘on the record,’ ‘off the record,’ daily briefings. But the flip side of that was they were exerting control over what the media could say. So, for a period of now, 24 years, Number 10 has progressively been controlling the narrative. There is a relentless Number 10 media campaign to ensure that none of the mainstream media outlets step out of line from where the government is at. And if they’re called “D notices”, well, this is where the government says ‘These are our lines’—a bit like what the presidential administration in Moscow does.

Carden: So when were you in Moscow, in 2014? Were you there because they needed to staff up because of the craziness that was…

Proud: No, I chose to go.

Carden: Okay. So you were there at the very beginning of this terrible story that’s been going on in the Donbas?

Proud: Well, in fact, it precedes that because I organized theG8 Summit in Britain that Vladimir Putin attended. So I’m the only member of the current generation of people from the diplomatic service who’d actually seen Vladimir Putin on his last visit to the UK. And that prompted me to apply because Russia was due to take the G8 presidency in 2014.

And that drove my decision at a time when UK-Russia relations were in a much better, healthier shape than obviously where they are now, which is no shape at all.

It was clear to me right from the beginning, the Embassy in Kiev went totally native: Russia’s evil, we need to support the anti-terrorist operation. And they just totally bought into that narrative from the start. And indeed, the operation in London was on the same wavelength. And it was really, really difficult for the Ambassador in Moscow to get the Russian perspective heard in London.

Carden: So you were there during the Michael McFaul experiment?

Proud: Experiment. Yeah. Well, I mean, the latter end of it. I think he probably left just as I was arriving because he totally screwed up.

Carden: I assume your guy was more professional and knowledgeable about the region than…

Proud: Yeah, Tim Barrow. He is an astoundingly good diplomat—super talented guy who also served as Ambassador in Kiev. And he was going back and forth to London pretty much every week trying to bring a more nuanced perspective. And it was a constant struggle to introduce the Russian perspective into policy thinking.

Carden: In the States, even among people I know who know better, professors, journalists and the like, they go on TV and they say that the war has nothing to do with NATO. Do they trot out that line here?

Proud: You’ll find, particularly when you listen to people like Boris Johnson, that it’s all about, well, you can’t deny Ukraine a choice to join [NATO]. Well, no, you can’t. But you can’t deny Russia the right to say, well, actually, we’re not very happy about that.

Carden: NATO’s a military alliance, and we have every right to say to them: No…

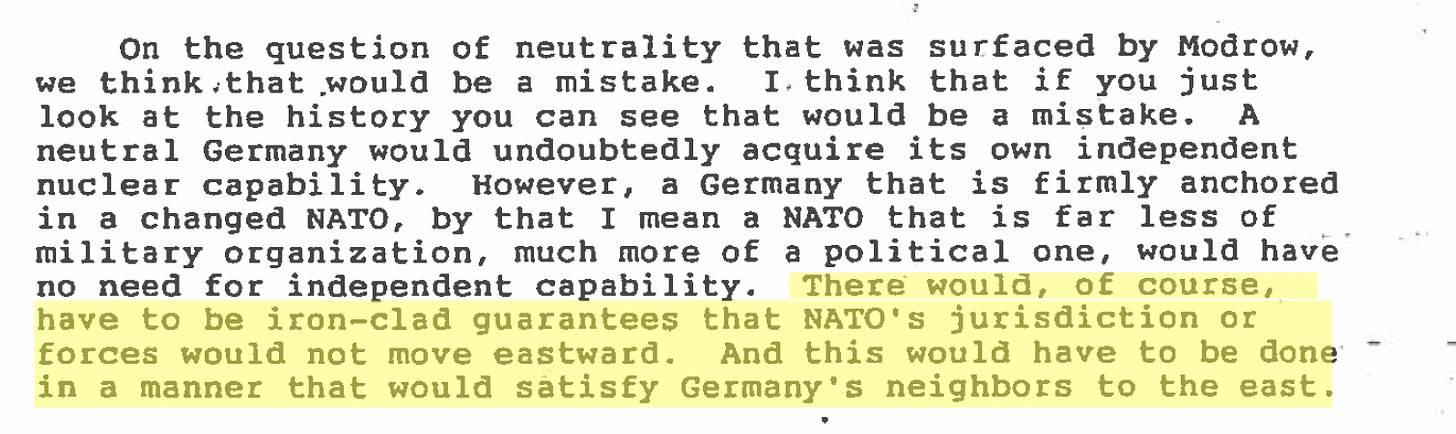

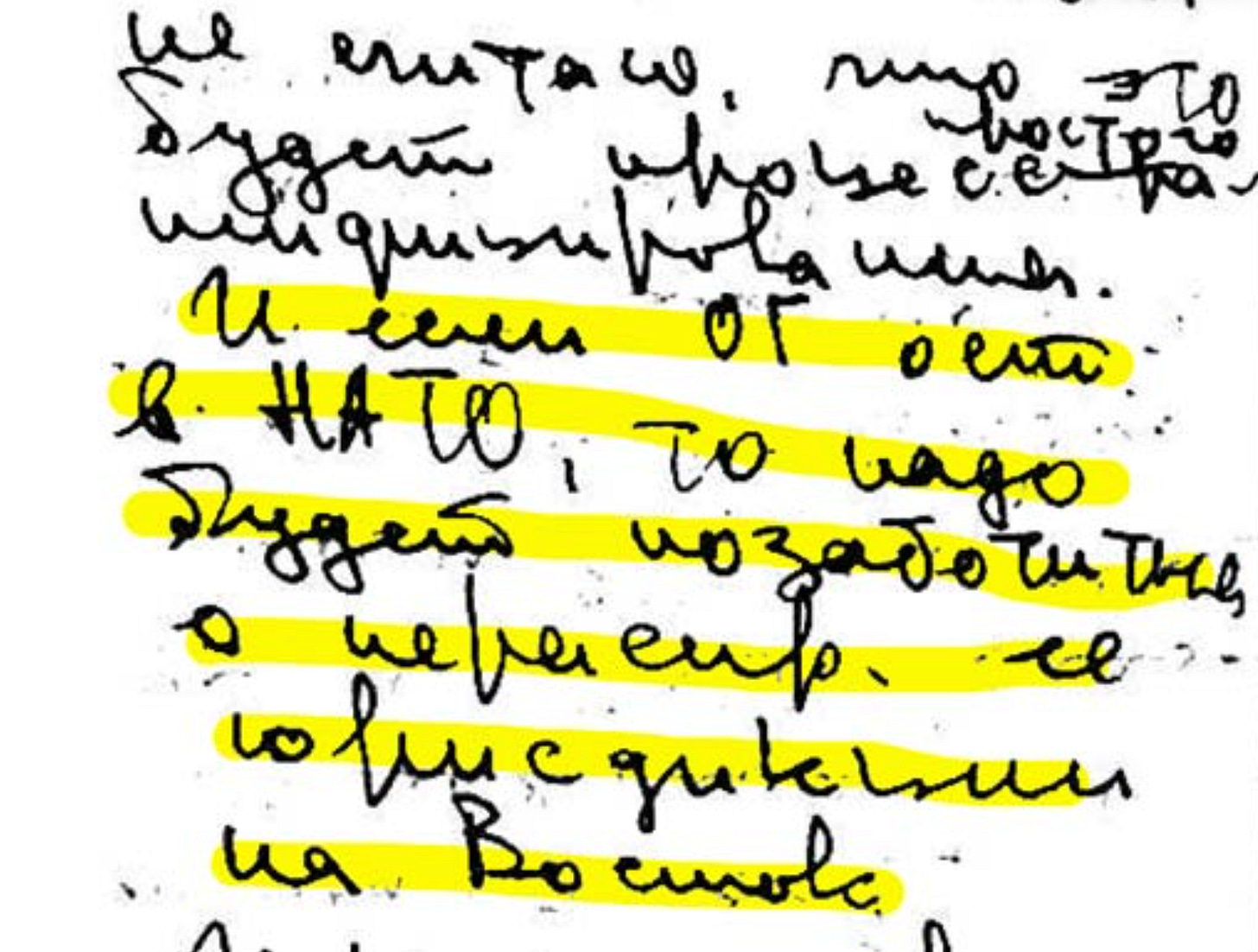

Proud: And the point about NATO is that actually Russia’s concerns about NATO had been clear since at least 2008. This wasn’t a surprise. And in fact, you could say right back to 2006 when the Balts joined NATO, Russia had concerns, but there was still quite good collaboration between Russia and NATO. I mean, NATO was still shipping weapons to Afghanistan via Russia and Uzbekistan…

Carden: Through the Northern Distribution Network…

Proud: Exactly, and even after the 2008 Bucharest summit, there was good NATO-Russia collaboration. But Putin in 2007 at the Munich conference and then in 2008 with [the war in Georgia], he’s saying, well, look guys, NATO is a problem for us. And he was ignored.

He was ignored. And unless we accept the fact that he was ignored, we’ll never get past this…

Carden: Whatever anyone thinks about Putin, that’s the point.

Proud: That’s the point. Everything has become personalized. It shouldn’t matter what you think of Putin, it’s irrelevant. It shouldn’t matter what you think of Zelensky. It’s irrelevant. You should look at the issues, the interests and decide on the basis of that.

Carden: Lavrov and Putin have always been admirably clear as to what their red lines are, crystal clear. There’s no mystery. And we still pretend like we don’t understand why they’re acting this way….

Proud: And the thing is, that is Russia’s only demand. When I lived in Moscow all signs were that Russia wanted to strengthen economic ties with us. They were always, always, always going to us saying, well, we actually want our relationship to be in a better shape than it is now. And we were saying, nooooo, after Crimea and the Donbas, obviously we can’t do that.

Carden: It’s ridiculous. Of course, now it’s gotten even crazier. There’s now this push among academics and some of the more warmongering journalists in the West to “decolonize” Russia….

Proud: More Ukrainian propaganda…

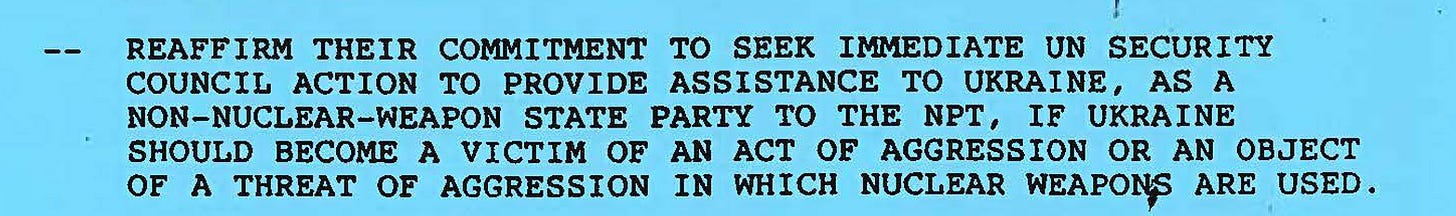

Carden: Let’s totally destabilize a country with over 1,500 strategic nuclear warheads. That’s a great idea….

Proud: And even Kaja Kallas, the supposed top diplomat from that titan of geopolitics, Estonia, has said that. It’s nonsense.

It is about bringing the grown-ups back into the conversation. The key aim for that 27th of February meeting between Trump and Starmer was to kind of shift the narrative—because of where the Labour party had been at in terms of criticizing Donald Trump in the past—a stupid thing to do, given the risk that that person could eventually again become the president of the United States.

There’s a huge amount of damage limitation that Starmer has to do now, having gotten off to such a bad start with Trump. But I think the ‘feel good’ vibes of a state visit is part of that package of putting Starmer in a better place.

You saw the way he went against Trump just before the Oval Office meeting, Hegseth said, Ukraine joining NATO is unrealistic, but Starmer said, Ukraine’s membership is irreversible. President Trump said, Zelensky is a dictator. Starmer replied Zelensky is a Democrat.

But after the 27th of February, that narrative has changed.

Starmer is actively avoiding saying anything which suggests any difference with President Trump. And that is a very significant shift in tone—because he’s been told that, actually, he can’t carry on just being the counterpoint to Trump.