By Stephen Bryen, Asia Times, 8/23/23

If the Ukraine war ended tomorrow, the United States still would need to send hundreds of billions in aid to that country. The bill includes continuation of military assistance, budget support for the Ukrainian government and reconstruction assistance.

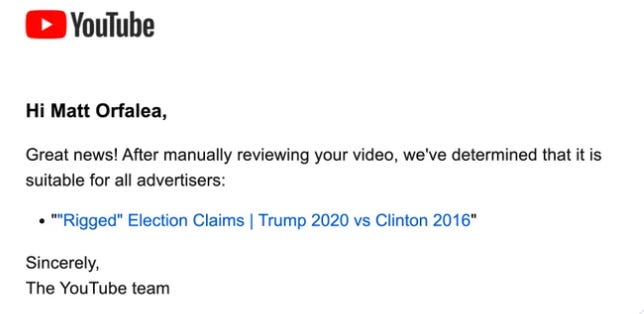

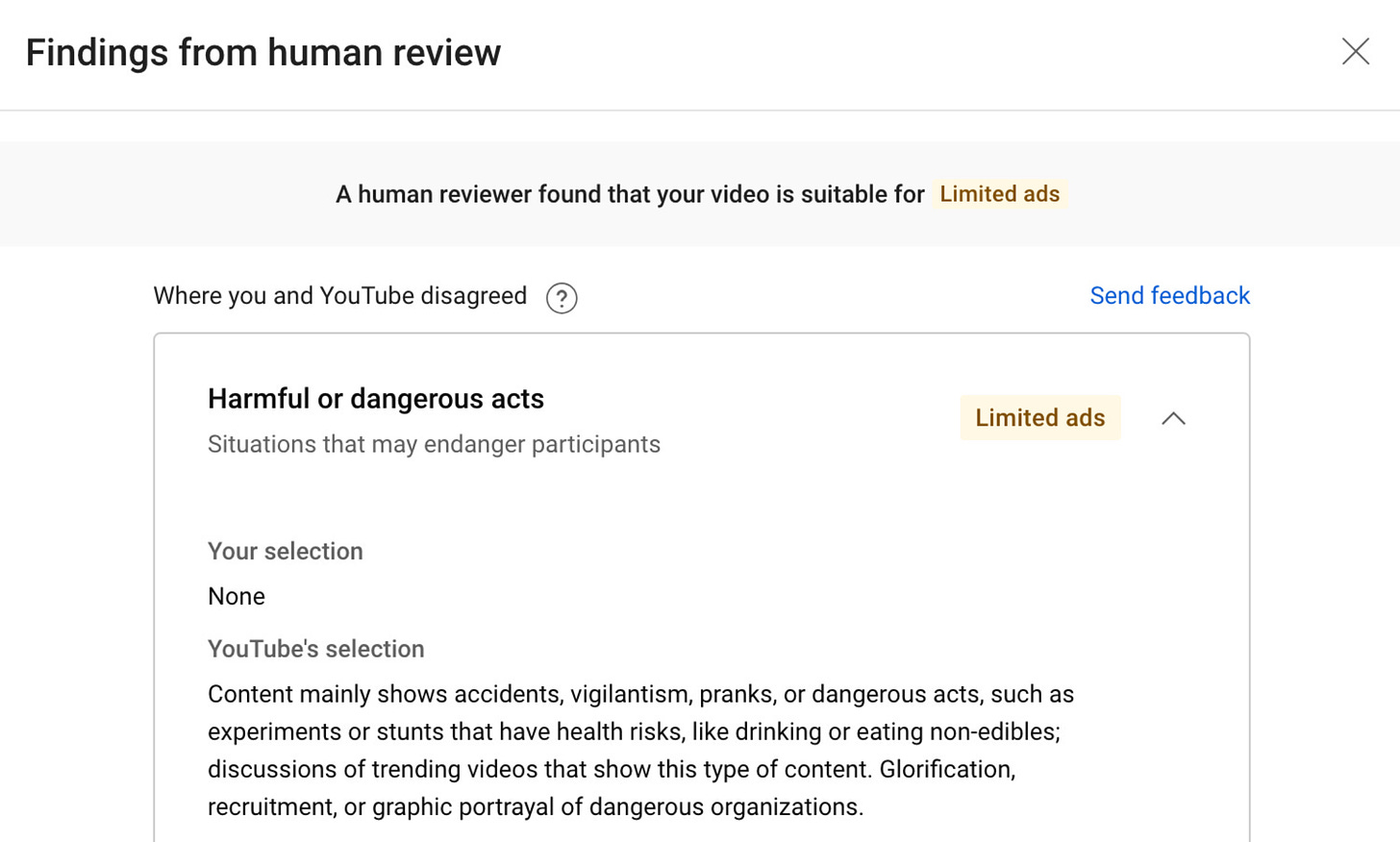

President Biden has just asked for another US$24 billion to support Ukraine, primarily for military equipment but also budget support ($7.3 billion). While Congress is increasingly skeptical about another huge chunk of money to fund an endless conflict, this is peanuts compared with what will be asked after the war ends.

The World Bank has done a revised estimate on reconstruction needs, based on data from the first year of the war (February 2022 to February 2023). The Bank says that Ukraine needs $411 billion for reconstruction over a ten-year period.

That estimate will need to be significantly increased to account for February to August 2023 and beyond. It would make sense to think that even if the war stopped tomorrow, reconstruction aid would come to $600 billion or more, or more than half a trillion dollars.

For purposes of comparison, the war in Iraq featured a reconstruction program of $60 billion. The US also spent $90 billion over twelve years to support Afghanistan (although the war continued in that country.)

There is no doubt that most of the US assistance to Afghanistan was probably stolen or went over to the Taliban. On top of that, billions’ worth of US war-fighting equipment was left in place and is now used by the Taliban.

In the case of Iraq, most of the aid was wasted thanks to bad management, corruption and poor planning.

The US and its allies will need to cough up $60 billion annually to support Ukraine, and expect that a lot of it will be stolen. It will have to keep the funding up for 10 years.

Consider that Germany has committed to support Ukraine “for as long as it takes” at $5 billion annually. But the German government in power is likely to be replaced soon, and that pledge is about as worthless as the Weimar mark.

Likewise, the UK economy is very dodgy, and finding serious money in future will prove a real challenge. The bottom line is that most of the money will have to come from Uncle Sam.

It may be that some Washington insiders are thinking that the best thing is to prolong the war as long as possible, because if the fighting continues the US just needs to provide military assistance and budget support for the government, but not reconstruction assistance.

In effect, that is the Biden administration policy. By continuing the war the Biden government thinks it can convince Congress to keep paying and they can keep Ukraine “alive” by forking over arms and money to pay salaries and for needed supplies.

But will Congress be willing to keep spending for an endless war? It is likely Congress will want to know where the money is going, how it is used, and how the US government accounts for its spending.

Most Americans oppose more aid to Ukraine. We are entering an election period with the first Republican presidential debates coming soon. Ukraine is sure to be an issue and some candidates, like Robert Kennedy Jr, who identifies for the time being as a Democrat, already are speaking out against supporting the war.

This could mean Biden will have a huge problem trying to get a skittish Congress, including his fellow Democrats, to sign up for more spending on a losing proposition.

It has long been understood that Ukraine is a corrupt country. Ukrainian politicians, including Zelensky, have offshored some of their wealth (Zelensky has a villa in Tuscany on the seashore in Forte dei Marmi which he bought before he entered politics and now rents to Russian clients at 12,000 euros a month).

President Biden’s son Hunter is embroiled in an investigation of payments and other activities centered partly on Ukraine’s Burisma energy holding company and in part on transactions in China. A Republican-dominated committee in the House of Representatives has sought to tie the president to the matters under investigation.

When the “big” reconstruction money starts flowing, assuming that happens, political and military officials in Ukraine will enthusiastically help the United States line their pockets.

Ukraine’s corruption was highly visible this month as President Zelensky fired all the military recruiters in the country because they were selling recruitment passes to young men seeking to avoid the war.

Ukraine will end up being the most costly operation ever carried out by the United States. The US Marshall Plan for European reconstruction after World War II cost the United States $13.3 billion. That amount, in 2023 dollars, would be $173 billion, roughly a third of what reconstruction would cost for Ukraine.

There will be a strong lobbying effort by some US companies that anticipate getting rich providing support to Ukraine (these in addition to the usual suspects in defense industries).

We have seen them before in the Iraq reconstruction exercise. This lobbying will provide bait to Democrats and Republicans who otherwise might walk away from the war. But will it be enough to go against the will of American voters?

Americans can rightly ask: What are we getting for these huge outlays that will seriously burden US taxpayers? The US policy on Ukraine is a disaster from many angles, but for sure one of them is the huge dollar cost in supporting this endless misadventure.