YouTube link here.

Is a Ukraine Peace Deal Possible? Quincy Institute debate between George Beebe & John Mearsheimer

YouTube link here.

YouTube link here.

YouTube link here. This was recorded earlier today.

Iran Prepared for an Existential War. How Much Are Trump and Israel Willing to Gamble?

By Jeremy Scahill & Murtaza Hussain, Drop Site News, 3/1/26

On Saturday, President Donald Trump went to TruthSocial to announce the U.S. and Israel had been successful in assassinating Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. “Khamenei, one of the most evil people in History, is dead,” Trump wrote. “He was unable to avoid our Intelligence and Highly Sophisticated Tracking Systems and, working closely with Israel, there was not a thing he, or the other leaders that have been killed along with him, could do.”

The New York Times followed with a breathless account published Sunday purporting to tell the secret story of how the CIA and Israel hunted down Khamenei, “tracking him for months” and “gaining more confidence about his locations and his patterns,” before pinpointing his location so he could be killed. “People briefed on the operation described it as a product of good intelligence and months of preparations,” the report claimed.

Khamenei’s secret location, it turned out, was simply his office.

The U.S. and Israel have consistently claimed Khamenei was in hiding. “This is basically just fabricated drama to make Trump look bigger and more dramatic than he really is,” a senior Iranian official told Drop Site. He spoke on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak about internal matters.

Iran’s Supreme National Security Council “personally recommended to [Khamenei] that he relocate, change his workplace, and even adjust his living arrangements for safety reasons,” the Iranian official said. “But [Khamenei] had a completely different perspective on moving—he insisted on keeping things as normal and ordinary as possible, without seeking extra security measures or standing out in any way.”

For breaking news updates, follow Drop Site News on X.

Ali Larijani, the chair of Iran’s Supreme National Security Council said Iranian officials anticipated that the U.S. and Israel would target Khamenei. “They decided to strike him first. This analysis was also circulating among military circles—that they were pursuing exactly this objective,” he told Iranian state TV after Iran confirmed Khamenei was killed.

“This event is an extraordinarily bitter one for us,” Larijani added. “America and the Zionists, through this act, have effectively created a situation for Iran—for the Iranian people—that we must say: You have burned the heart of the Iranian people. We will burn your hearts in return.”

As of Sunday morning, the Iranian Red Crescent and state-linked media have reported preliminary casualty figures of over 200 people killed and more than 740 injured across Iran, though the actual toll is expected to be significantly higher. One strike on a girls’ elementary school in Minab killed 165, according to the state-run IRNA news agency.

Within hours of the U.S.-Israeli bombing, Iran began launching barrages of ballistic missiles at Israel in attacks that have so far killed at least 11 people and injured several hundred. On Sunday morning, an Iranian missile struck a building near Jerusalem, in an attack that is estimated to have killed at least nine people in a bomb shelter.

“The Islamic Republic of Iran considers bloodshed and revenge against the perpetrators and commanders of this crime as its legitimate duty and right, and will fulfill this great responsibility and duty with all its might,” Pezeshkian said Sunday in a statement carried on state TV.

Iran has also unleashed a series of sustained missile and drone attacks against U.S. military facilities across the Persian Gulf, striking the United Arab Emirates, Bahrain, Saudi Arabia, and Qatar, as well as targets in Jordan. The UAE reported three deaths and 58 minor injuries in Iranian strikes, with most of those impacted believed to be foreign workers. Dubai International Airport, the world’s busiest airline hub, was also damaged and partially shut down after an unidentified projectile struck one of its concourses. Two were also killed in Iraq and one in Kuwait.

The attacks have also drawn the first acknowledged U.S. military casualties of the war. In a statement early Sunday, U.S. Central Command announced that three American service members had been killed and five others seriously wounded during “Operation Epic Fury,” adding that several other additional personnel had sustained minor shrapnel injuries. The soldiers killed had been deployed to a base in Kuwait supporting the operation, U.S. officials told NBC News.

Iranian officials have said their initial response to the U.S.-Israeli bombing, while unprecedented in scope, did not represent the full force of Tehran’s potential retaliatory strikes.

The Saturday strikes on Khamenei’s office wiped out the top echelon of Iran’s political and military structure and killed several of the late Supreme Leader’s family members. Iran, which has spent decades investing in a horizontal leadership structure to defend against this type of attack, announced a new leadership structure. Along with President Masoud Pezeshkian, Iran’s new interim leadership council includes Gholam-Hossein Mohseni-Ejei, the head of Iran’s judiciary, and Ayatollah Ali Arafi, a prominent member of Iran’s Guardian Council and Assembly of Experts—the body that is ultimately responsible for choosing the country’s Supreme Leader.

The White House said President Trump intends to speak with what a U.S. official called the “new potential leadership” of Iran in the coming days and Trump has suggested the war may be shorter in duration than he initially projected. “They want to talk, and I have agreed to talk, so I will be talking to them. They should have done it sooner. They should have given what was very practical and easy to do sooner. They waited too long,” Trump told The Atlantic. “They could have made a deal. They should’ve done it sooner. They played too cute.”

For now, Trump said in a post on Truth Social, “heavy” bombing would continue “uninterrupted throughout the week or, as long as necessary.”

In a pre-recorded message on Sunday afternoon, Trump said, “I once again urge the Revolutionary Guard, the Iranian military, police to lay down your arms and receive full immunity or face certain death. It will be certain death. Won’t be pretty. I call upon all Iranian patriots who yearn for freedom to seize this moment.”

Likewise, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu said Israel would expand its strikes. “In the coming days, we will strike thousands of targets of the terrorist regime,” Netanyahu said in a video posted on social media. “We will create the conditions for the brave people of Iran to free themselves from the chains of tyranny.”

Trump said he still believes there will be an uprising in Iran spurred by the U.S.-Israeli bombings and assassinations. “I think it’s gonna happen,” Trump told the Atlantic.

“Everyone said that if Ali Khamenei is killed the people will come into the streets to overthrow the regime, and so far that has not happened. Some people have cheered, but overall the system is quite resilient,” said Sina Azodi, director of Middle East studies at Georgetown University. “One thing the Israelis have tried for the past two years is decapitating the top echelon of their enemy and expecting them to implode tomorrow. That works well against non-state actors, but not against a state actor that is quite resilient, has a constitution and other structures in place, and that in its early years already had to go through the experience of total war and leadership assassinations.”

Hooman Majd, an Iranian-American political analyst who served as an advisor to former Iranian President Mohammed Katami, said Iran has been preparing for major U.S.-Israeli attacks since the 12-day war last June, during which more than 1,000 Iranians were killed, including senior military commanders. “Their military leadership is quite deep in terms of both the regular army, the IRGC, and the Navy. They have an ability to sustain a war, perhaps even longer than the U.S. wants to,” Majd told Drop Site. “There will come a point at which Trump may decide Trump is the one who wants the off-ramp, not Iran.”

Watch Drop Site’s full conversation with Majd here.

Majd said that if Iran decided to start targeting oil infrastructure in the Persian Gulf or completely shut off access to the Strait of Hormuz, the economic consequences would be significant. “A financial hit on America and Western Europe is something that nobody wants for a long period of time, certainly not Trump,” he said. “So there’s going to be an advantage for Trump to have [an off ramp]. But if he really believes that Iran is then going to come in and say, ‘Enough, we give up, whatever you want, we’ll do,’ that’s very unlikely.”

Iran, meanwhile, has said it remains open to diplomacy and has denounced the U.S. “deception” in the purported negotiations that preceded the bombings that began Saturday morning. Technical talks were scheduled for Monday in Vienna. Oman’s Foreign Minister, Badr Al Busaidi, the chief mediator of the talks between Iran and the U.S., said Sunday he had spoken with Iran’s Foreign Minister Abbas Araghchi. In a statement, Al Busaidi called for a ceasefire and said that Araghchi told him Iran was open “to any serious efforts that contribute to stopping the escalation and returning to stability.”

In an appearance Sunday on ABC’s This Week, Araghchi was asked by host George Stephanopoulos if a diplomatic resolution was still possible. “You answer this question,” Araghchi shot back. “We negotiated with the United States twice in the past 12 months. And in both cases, they attacked us in the middle of negotiation. And that has become a very bitter experience for us.”

Dr. Foad Izadi, a professor at the University of Tehran, said that Iranian forces still have not used their most powerful weapons systems, including its hypersonic and long-range ballistic missiles, in retaliatory strikes against Israel and U.S. bases and vessels in the region. If meaningful steps toward a ceasefire or a return to diplomatic talks do not emerge soon, he said, Iran is likely to intensify its military responses.

“[Iranian leaders] are getting this idea that you either use it or lose it. Iran has some capabilities and the other side is hitting these capabilities, so the sense is that Iran should use these capabilities as long as they remain available,” said Izadi, a prominent supporter of the Iranian government, in an interview with Drop Site. “They have to basically measure how much they can use, when they can use it, keeping in mind that they may not be able to access these stockpiles if they wait too long. But when you lose senior commanders, then sometimes making decisions on these issues becomes more difficult.”

The Gulf states have issued strong denunciations of “Iranian aggression” against them, while avoiding explicit demands for an end to the U.S. attacks that are being launched with the use of military and intelligence facilities on their soil.

“To the countries of the region: We are not seeking to attack you,” said Larijani, one of the central figures directing Iran’s current strategy. “When the bases located in your country are used against us, and when the United States carries out operations in the region relying on these forces, then we will target those bases. For these bases are not part of the land of those countries; rather, they are American soil,” he wrote on X.

But Iran has not only struck U.S. military facilities. It has also hit civilian airports in Kuwait, Bahrain, Abu Dhabi, and Dubai, as well as hotels and other buildings in the UAE and Bahrain. “We have begun targeting their military bases. They evacuated their bases and moved into hotels, turning civilians into human shields,” Araghchi charged in an interview with Al Jazeera. “We are trying to target only military personnel and facilities assisting U.S. operations against Iran.”

On Sunday, an Iranian strike also hit a port in Oman, the central mediator in the recent negotiations between Iran and the US. Araghchi said the strike was not intended as an attack on Oman and indicated that it was the result of pre-selected targets developed before the war began. “We have already told our Armed Forces to be careful about the targets that they choose,” he told Al Jazeera. “Our military units are now, in fact, independent and somehow isolated, and they are acting based on general instructions given to them in advance.”

The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia summoned the Iranian ambassador on Saturday and issued a statement condemning what it described as “cowardly Iranian attacks” targeting its territory. In a Sunday interview with CNN, United Arab Emirates Minister of State for International Cooperation Reem Al-Hashimy conveyed a similar combative stance, saying that the UAE won’t “sit idly by.” The UAE also said it had closed its embassy in Tehran and withdrawn its ambassador and diplomatic mission.

In an extraordinary meeting held via video conference on Sunday, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) condemned “treacherous Iranian attacks” on GCC countries and Jordan and stated that it will take “all necessary measures to defend its security and stability,” including the option to “respond to the aggression.” The GCC said that attacks happened despite “repeated assurances that their territories would not be used to launch any attack” on Iran and urged for decisive action from the UN Security Council, “noting that the stability of the Gulf region is not only a regional concern but also a cornerstone of global economic stability and maritime navigation.”

Araghchi said that Iran’s Arab neighbors “should be angry at the United States and Israel,” adding, “They should not pressure us to stop this war; they should pressure the other side.”

Analysts have suggested that some of the targets hit by Iran in the opening phase of the war were selected because Iranian intelligence believed they housed Israeli intelligence and defense companies or personnel. The U.S. embassy in Bahrain evacuated government personnel from hotels and issued a warning for citizens to avoid hotels in the country after an Iranian strike on the Crowne Plaza Hotel in Manama.

“Right after the 12-day war, with the threat of a new regional conflict looming, Iran’s security and military agencies jointly put together a target bank that included potential strikes on American and Israeli personnel and forces if things escalated into a full-blown regional war,” the senior Iranian official told Drop Site. “The fact that they’ve now pinpointed the residences/locations of some of these forces has really caught the Americans and Israelis off guard. And yeah, the precision and targeting of these attacks are getting sharper and more focused by the day.” There has been no independent confirmation that any of the sites hit by Iran housed Israeli intelligence facilities or personnel.

“The UAE is host to a lot of Israeli intelligence companies, arms companies, and Iran considers those offices legitimate targets because they’re Israeli targets,” Izadi said. “The UAE government has allowed Israelis to basically have an unofficial base in different parts of UAE. Part of the Israeli operation against Iran is run out of the UAE. So Iran has been monitoring these places.”

On Sunday, the Israeli Broadcasting Authority reported that an Iranian drone struck an apartment inhabited by Israelis in Abu Dhabi near the Israeli embassy. The UAE is one of the only Muslim countries in the world to have normalized relations with Israel and officials from both countries often publicly celebrate their close ties.

Amid a wave of attacks on targets in the UAE including iconic buildings like the Burj al-Arab hotel, which was reportedly struck by a drone, multiple fires visible from satellite imagery also broke out at one of the berths at Jebel Ali Port after debris from what local authorities claimed was as an “aerial interception” struck the area. Jebel Ali is the largest container shipping port in the Middle East and a critical node in the Emirati economy. DP World, which operates the facility, announced that it was suspending operations at the port temporarily in response to the attack.

The leaders of France, Germany and the UK issued a joint statement Sunday that appeared to indicate they may get involved directly with the U.S.-Israeli war. “We will take steps to defend our interests and those of our allies in the region, potentially through enabling necessary and proportionate defensive action to destroy Iran’s capability to fire missiles and drones at their source,” they wrote. “We have agreed to work together with the US and allies in the region on this matter.“

Faced with an existential war, Iran has long signaled it could retaliate by striking the global economy—including by hitting oil facilities around the Persian Gulf. In addition to the attacks on Jebel Ali, at least two ships, including an oil tanker, in the strategically vital Strait of Hormuz were also hit by projectiles over the past 24 hours. The Iranian government has warned ships not to attempt to cross the strait, through which roughly 20% of global oil and gas production flows. As of Sunday, over 200 ships, including at least 150 oil and gas tankers, are estimated to have dropped anchor outside the waterway, while commercial traffic has plunged 70%. Oil prices have already risen by over 10% to over $80 a barrel and could rise above $100 in the event of further escalation.

“Iran’s strategy and only real option is to continue attacking and increase the costs on the Americans and U.S. allies. Part of that strategy of increasing costs means attacking the GCC countries but also hitting U.S. bases in the region. We have now seen the three Americans killed and the Iranians know that Americans are sensitive to casualties including in a midterm election year,” said Azodi. “For Iran, an ideal scenario might be to fight for three to four weeks after which there is no clear winner at the end—they are trying to increase pressure in every way. They cannot win the war but they can absorb a lot of punishment and can force it to stop.”

Jawa Ahmad, Drop Site’s Middle East research fellow, contributed to this report.

***

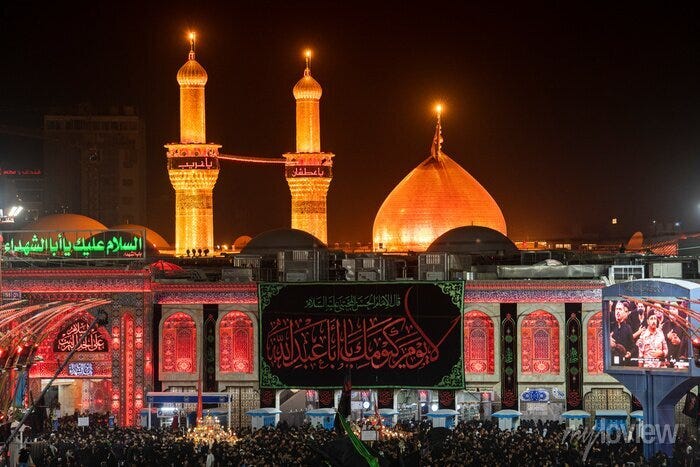

War Without Collapse: The Power of Shiʿa Islam, Martyrdom and the Iranian Nation

By Kautilya The Contemplator, Substack, 2/28/26

The war that erupted against Iran on February 28, 2026, is from Tehran’s perspective, an existential struggle. The American-Israeli objective has been stated explicitly: dismantle the command structure, fracture elite cohesion and accelerate political collapse of the Iranian state from above.

For Iran, the stakes are civilizational. The conflict is framed not as a contest over policy, but as a battle for sovereignty, independence and historical continuity. The memory of foreign interventions – whether in the form of the 1953 coup, support for Iraq during the 1980–1988 war, or successive sanctions regimes – shapes how the present moment is interpreted. In that historical context, the current campaign is seen not as a discrete military episode, but as the latest chapter in a long struggle over who determines Iran’s political destiny.

The cost has already been immense. Reports indicate that senior members of Iran’s political and military leadership were killed in the opening wave of strikes, notably the defense minister Amir Nasirzadeh and the head of the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC) Mohammed Pakpour. Most consequential is the now confirmed death by Iranian state media of the Supreme Leader, Ayatollah Ali Khamenei. In conventional strategic logic, such decapitation is intended to disorient the state, weaken morale and trigger internal fragmentation. Leadership removal is assumed to create paralysis. US President Donald Trump, in his Truth Social post of February 28, announcing the death of Khamenei, stated that “This is the single greatest chance for the Iranian people to take back their Country.”

Yet, this assumption rests on a profound misunderstanding. Iran is not merely a modern nation-state with a centralized bureaucracy. It is also the historical heartland of Shiʿa Islam – a tradition in which the death of a leader can generate consolidation rather than collapse. The West often interprets martyrdom as tragic loss. In Shiʿa political theology, martyrdom carries an entirely different resonance. It is sanctified sacrifice. It is moral vindication. It is the ultimate testimony to righteousness in the face of tyranny. This difference in moral grammar matters enormously in wartime.

In such a framework, the killing of leaders by foreign powers does not necessarily delegitimize the political order. It can instead sacralize it. Loss becomes proof of injustice inflicted. Death becomes evidence of steadfastness. The fallen are absorbed into a sacred narrative that stretches back nearly fourteen centuries. This is the force that external strategists routinely underestimate.

To understand why this war is unlikely to break Iran as a political community, one must first understand the power of Shiʿa Islam in Persian history and the central role martyrdom has played in shaping Iranian identity. Only then does it become clear that what appears externally as decapitation may internally become consecration.

At the same time, one must caution that this religious dimension is not the only factor shaping Iran’s resilience. There are other structural factors such as elite cohesion, security control and institutional depth that matter. However, religious ideology is a force that external strategists consistently underestimate in Iran. And in wartime, it can profoundly alter how loss is processed, how legitimacy is reinforced and how political continuity is maintained.

The central event of Shiʿa Islam is the martyrdom of Imam Husayn ibn Ali at the Battle of Karbala (present day Iraq) in 680 CE. In Shiʿa tradition, Husayn’s death was not a mere battlefield tragedy. It was a cosmic confrontation between justice and tyranny. His refusal to submit to illegitimate authority became the archetype of righteous resistance.

For Shiʿa communities, history is not cyclical but moral. Karbala is re-enacted ritually every year during Ashura. In Iran, millions participate in mourning processions, passion plays (taʿziyeh) and acts of collective remembrance. These rituals do not simply commemorate the past. They socialize each generation into a worldview in which suffering, sacrifice and endurance under oppression are spiritually ennobling.

This matters profoundly in wartime. A society steeped in the narrative of Karbala does not experience loss the way secular strategic theory assumes. Casualties can be framed as martyrs. Leadership decapitation can be reframed as continuity with Imam Husayn’s path. External violence can be woven into an ancient story in which injustice ultimately fails and righteousness endures. No airstrike can bomb that narrative out of existence.

The decisive historical moment in which Shiʿism fused with Iranian statehood came in the early 16th century under the Safavid dynasty. Shah Ismail I declared Twelver Shiʿism (Ithnā ‘Asharīyah) the official religion of the Persian realm. This was not merely theological. It was geopolitical.

By distinguishing Iran from its Sunni Ottoman rivals, the Safavids created a religious boundary that reinforced territorial sovereignty. Shiʿism became a civilizational marker of “Iranianness.” Over time, Persian language, imperial memory and Shiʿa doctrine intertwined.

This synthesis endured dynastic change. It survived invasions, internal upheaval and imperial decline. By the modern period, Shiʿism was not simply a creed. It was a pillar of national consciousness.

Thus, when modern Iran faces foreign pressure, it does not interpret events solely in contemporary political terms. It perceives them through centuries of state-religion integration. The defense of sovereignty becomes inseparable from the defense of sacred history.

The 1979 Iranian Revolution drew heavily upon Shiʿa symbolism. Ayatollah Khomeini cast opposition to the Shah not as a conventional political movement but as a re-enactment of Husayn’s stand against Yazid. Martyrdom imagery suffused revolutionary rhetoric.

During the Iran–Iraq War (1980–1988), this symbolism intensified. Young volunteers were encouraged to see the battlefield as Karbala. The fallen were not casualties. They were shuhada, or martyrs. Murals of martyrs adorned cities and funeral processions became mass political rituals reinforcing solidarity.

The war itself – launched by Saddam Hussein but supported materially by Western and regional powers – was perceived as an existential assault on the revolution. Instead of collapsing under pressure, Iran consolidated. Institutions hardened and a siege mentality deepened.

The lesson internalized by the Iranian state was clear in that external aggression does not automatically produce fragmentation. It can produce cohesion, especially when framed as sacred defense.

Western strategic thought often assumes that targeted killing weakens adversaries by demoralizing followers. In highly secular political cultures, that assumption may hold. However, in Shiʿa political theology, martyrdom is an accelerant. When a leader like Ali Khamenei is killed, the narrative does not necessarily end. It intensifies.

This dynamic was visible after the assassination of the IRGC General Qasem Soleimani in 2020. Rather than sparking immediate regime instability, his death triggered massive funeral processions and reinforced anti-American sentiment across segments of Iranian society. Soleimani was recast as a defender of the nation and the faith. His image became ubiquitous.

When a Supreme Leader is killed by foreign powers, the symbolic resonance will be even greater. The event will be framed as proof of longstanding hostility toward Iran’s independence. The leader’s death will be sacralized, not trivialized. In such an environment, external force risks strengthening precisely what it aims to shatter.

External observers consistently assume that Iran’s political system is personality-driven and therefore vulnerable to decapitation. In reality, the Islamic Republic has institutionalized succession mechanisms through the Assembly of Experts. The Supreme Leader’s role is embedded within a constitutional framework that anticipates mortality.

At 86, Khamenei’s age alone would have necessitated contingency planning. Iranian elites have long understood the inevitability of transition. The idea that leadership change equals systemic collapse misunderstands both the theological and institutional architecture of the state. Shiʿa doctrine, after all, developed during centuries in which the rightful Imam was believed to be in occultation. Authority structures evolved precisely because the ultimate spiritual leader was absent.

Political continuity amid leadership absence is not alien to Shiʿa thought. It is foundational to it. Indeed, following the reported killing of senior commanders, Brigadier-General Ahmad Vahidi has already been named the new IRGC commander, signaling rapid institutional continuity rather than paralysis. Iranian state media has also indicated that a new Supreme Leader will be announced shortly.

Thus, the killing of a leader in the Islamic Republic does not create a vacuum. It could instead activate pre-existing succession pathways and re-legitimize the system through ritual mourning, institutional reaffirmation and the sacralization of continuity. In a political culture shaped by Karbala, loss does not automatically produce fragmentation. It can produce consolidation.

Iranian nationalism is not reducible to religion. It draws upon pre-Islamic imperial memory of the Achaemenids, Parthians, Sassanians and a deep literary tradition. However, Shiʿism became the vessel through which much of that historical memory was preserved and politicized.

When contemporary Western powers apply military pressure, they enter a historical landscape already saturated with memories of intrusion. Shiʿa martyrdom narratives fuse seamlessly with nationalist grievances. The result is not a simple regime-versus-people dichotomy. It is a layered identity in which faith, history and sovereignty overlap.

In conventional military terms, strategic depth refers to geography and redundancy. In Iran’s case, there is also ideological depth. Martyrdom ideology ensures that losses do not automatically translate into demoralization. Instead, they can generate mobilization. Each fallen figure becomes part of an expanding pantheon of resistance.

This ideological depth complicates coercive strategies. Bombing may destroy assets. It may even kill leaders. However, it risks feeding the very narrative that sustains long-term defiance.

Shiʿa Islam’s theology of martyrdom, fused with Persian state identity and modern revolutionary memory, forms an unbreakable thread in Iranian political culture. Leadership succession mechanisms provide institutional continuity. Ritual mourning practices convert loss into unity. Historical memory reframes external assault as validation of long-held suspicions.

No US–Israeli war would operate in a vacuum. It would unfold within this deeply sedimented context in which attempts at coercion risk reinforcing cohesion.

To assume that killing a leader or launching a massive air campaign would shatter Iran is to misunderstand the very foundations of its national identity. The power of Shiʿa Islam in Persian history has been precisely the transformation of tragedy into endurance, of death into continuity.

Empires have come and gone across the Iranian plateau. Dynasties have risen and fallen. Yet, the narrative of Karbala endures. In the end, wars test not only military capacity but civilizational depth. Iran’s depth lies not only in missiles or mountains, but in memory – and memory, especially sacred memory, is extraordinarily difficult to break.

If you’ve found this analysis valuable, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber. Your support directly enables me to devote more time to deep research and long-form writing of this kind, free from algorithms and click-driven incentives.

By Ian Proud, Substack, 2/14/26

Since the war started, voices in the alternative media have said that Ukraine cannot win a war against Russia. Indeed, John Mearsheimer has been saying this since 2014.

Four years into this devastating war, those voices feel at one and the same time both vindicated and unheard. Ukraine is losing yet western leaders in Europe appear bent on continuing the fight.

Nothing is illustrative of this more than Kaja Kallas’ ridiculous comment of 10 February that Russia should agree to pre-conditions to end the war, which included future restrictions on the size of Russia’s army.

Comments such as this suggest western figures like Kallas still believe in the prospect of a strategic victory against Russia, such that Russia would have to settle for peace as the defeated party. Or they are in denial, and/or they are lying to their citizens. I’d argue that it is a mixture of the second and third.

When I say losing, I don’t mean losing in the narrow military sense. Russia’s territorial gains over the winter period have been slow and marginal. Indeed, western commentators often point to this as a sign that, given its size advantage, Russia is in fact losing the war, because if it really was powerful, it would have defeated Ukraine long ago.

And on the surface, it might be easy to understand why some European citizens accept this line, not least as they are bombarded with it by western mainstream media on a constant basis.

However, most people also, at the same time, agree that drone warfare has made rapid territorial gains costly in terms of lost men and materiel. There is a lot of evidence to suggest that since the second part of 2023, after Ukraine’s failed summer counter-offensive, Russia has attacked in small unit formations to infiltrate and encircle positions.

Having taken heavy losses at the start of the war using tactics that might have been conventional twenty years ago, Russia’s armed forces had to adapt and did so quickly. Likewise, Russia’s military industrial complex has also been quicker to shift production into newer types of low cost, easy build military technology, like drones and glide bombs, together with standard munitions that western providers have been unable to match in terms of scale.

And despite the regular propaganda about Russian military losses in the tens of thousands each month, the data from the periodic body swaps between both sides suggest that Ukraine has been losing far more men in the fight than Russia. And I mean, at a ratio far greater than ten to one.

Some western pundits claim that, well, Russia is advancing so it is collecting its dead as it moves forward. But those same pundits are the ones who also claim that Russia is barely moving forward at all. In a different breath, you might also hear them claim that Russia is about to invade Estonia at any moment.

Of course, the propaganda war works in both directions, from the western media and, of course, from Russian. I take the view that discussion of the microscopic daily shifts in control along the line of contact is a huge distraction.

The reality of who is winning, or not winning, this war is in any case not about a slowly changing front line. Wars are won by economies not armies.

Those western pundits who also tell you that Russia will run out of money tomorrow – it really won’t – never talk about the fact that Ukraine is functionally bankrupt and totally dependent on financial gifts which the EU itself has to borrow, in order to provide. War fighting for Ukraine has become a lucrative pyramid scheme, with Zelensky promising people like Von der Leyen that it is a sold investment that will eventually deliver a return, until the day the war ends, when EU citizens will ask whether all their tax money disappeared to.

Russia’s debt stands at 16% of its GDP, its reserves over $730 billion, its yearly trade surplus still healthy, even if it has narrowed over the past year.

Russia can afford to carry on the fight for a lot longer.

Ukraine cannot.

And Europe cannot.

And that is the point.

The Europeans know they can’t afford the war. Ukraine absolutely cannot afford the war, even if Zelensky is happy to see the money keep flowing in. Putin knows the Europeans and Ukraine can’t afford the war. In these circumstances, Russia can insist that Ukraine withdraws from the remainder of Donetsk unilaterally without having to fight for it, on the basis that the alternative is simply to continue fighting.

He can afford to maintain a low attritional fight along the length of the frontline, which minimises Russian casualties and maximises Ukraine’s expenditure of armaments that Europe has to pay for.

That constant financial drain of war fighting is sowing increasing political discord across Europe, from Germany, to France, Britain and, of course, Central Europe.

Putin gets two benefits for the price of one. Europe causing itself economic self-harm while at the same time going into political meltdown.

That is why western leaders cannot admit that they have lost the war because they have been telling their voters from the very beginning that Ukraine would definitely win.

At the start of the war, had NATO decided to back up its effort by force, to facilitate Ukrainian accession against Russia’s expressed objection, then the war might have ended very differently.

NATO would simply not have been able to mobilise a ground operation of sufficient size quickly enough to force Russia back from the initial territorial advances that it had made in February and March of 2022. That means, the skirmishes at least for the first month would have largely been in the form of air and sea assets, including the use of missiles.

There is nothing in NATO doctrine to suggest that the west would have taken the fight to Russia, given the obvious risk of nuclear catastrophe.

While it is pointless to speculate now, my view is that a short, hot war between NATO and Russia would have led to short-term losses of lives and materiel on both sides that forced a negotiated quick settlement.

Europe avoided that route because of the risk of nuclear escalation and the great shame of the war is that our leaders were nonetheless willing to encourage Zelensky to fight to the last Ukrainian, wrecking our prosperity in the process.

Who will want to vote for Merz, Macron, Tusk, Starmer and all these other tinpot statesmen when it becomes clear that they have royally screwed the people of Europe for a stupid proxy war in Ukraine that was unwinnable?

What will Kaja Kallas do for a job when everyone in Europe can see that she’s a dangerous warmonger who did absolutely nothing for the right reason, and who failed at everything?

Zelensky is wondering where he can flee to when his number’s up, my bet would be Miami.

So if you are watching the front line every day you need to step back from the canvas.

There is still a chance that European pressure on Russia will prevail, which makes this whole endeavour a massive gamble with poor odds.

More likely, when the war ends, Putin will reengage with Europe but from a position of power not weakness.

That is the real battle going on here.