This video cannot be embedded but Ritter’s analysis on his YouTube channel is worth watching. It starts at about the 3 minute mark.

Link here.

This video cannot be embedded but Ritter’s analysis on his YouTube channel is worth watching. It starts at about the 3 minute mark.

Link here.

The Postil, 9/1/22

The Postil (TP): You have just published your latest book on the war in Ukraine—Operation Z, published by Max Milo. Please tell us a little about it—what led you to write this book and what do you wish to convey to readers?

Jacques Baud (JB): The aim of this book is to show how the misinformation propagated by our media has contributed to push Ukraine in the wrong direction. I wrote it under the motto “from the way we understand crises derives the way we solve them.”

By hiding many aspects of this conflict, the Western media has presented us with a caricatural and artificial image of the situation, which has resulted in the polarization of minds. This has led to a widespread mindset that makes any attempt to negotiate virtually impossible.

The one-sided and biased representation provided by mainstream media is not intended to help us solve the problem, but to promote hatred of Russia. Thus, the exclusion of disabled athletes, cats, even Russian trees from competitions, the dismissal of conductors, the de-platforming of Russian artists, such as Dostoyevsky, or even the renaming of paintings aims at excluding the Russian population from society! In France, bank accounts of individuals with Russian-sounding names were even blocked. Social networks Facebook and Twitter have systematically blocked the disclosure of Ukrainian crimes under the pretext of “hate speech” but allow the call for violence against Russians.

None of these actions had any effect on the conflict, except to stimulate hatred and violence against the Russians in our countries. This manipulation is so bad that we would rather see Ukrainians die than to seek a diplomatic solution. As Republican Senator Lindsey Graham recently said, it is a matter of letting the Ukrainians fight to the last man.

It is commonly assumed that journalists work according to standards of quality and ethics to inform us in the most honest way possible. These standards are set by the Munich Charter of 1971. While writing my book I found out that no French-speaking mainstream media in Europe respects this charter as far as Russia and China are concerned. In fact, they shamelessly support an immoral policy towards Ukraine, described by Andrés Manuel López Obrador, president of Mexico, as “We provide the weapons, you provide the corpses!”

To highlight this misinformation, I wanted to show that information allowing to provide a realistic picture of the situation was available as early as February, but that our media did not relay it to the public. My goal was to show this contradiction.

In order to avoid becoming a propagandist myself in favor of one side or the other, I have relied exclusively on Western, Ukrainian (from Kiev) and Russian opposition sources. I have not taken any information from the Russian media.

TP: It is commonly said in the West that this war has “proven” that the Russian army is feeble and that its equipment is useless. Are these assertions true?

JB: No. After more than six months of war, it can be said that the Russian army is effective and efficient, and that the quality of its command & control far exceeds what we see in the West. But our perception is influenced by a reporting that is focused on the Ukrainian side, and by distortions of reality.

Firstly, there is the reality on the ground. It should be remembered that what the media call “Russians” is in fact a Russian-speaking coalition, composed of professional Russian fighters and soldiers of the popular militias of Donbass. The operations in the Donbass are mainly carried out by these militias, who fight on “their” terrain, in towns and villages they know and where they have friends and family. They are therefore advancing cautiously for themselves, but also to avoid civilian casualties. Thus, despite the claims of western propaganda, the coalition enjoys a very good popular support in the areas it occupies.

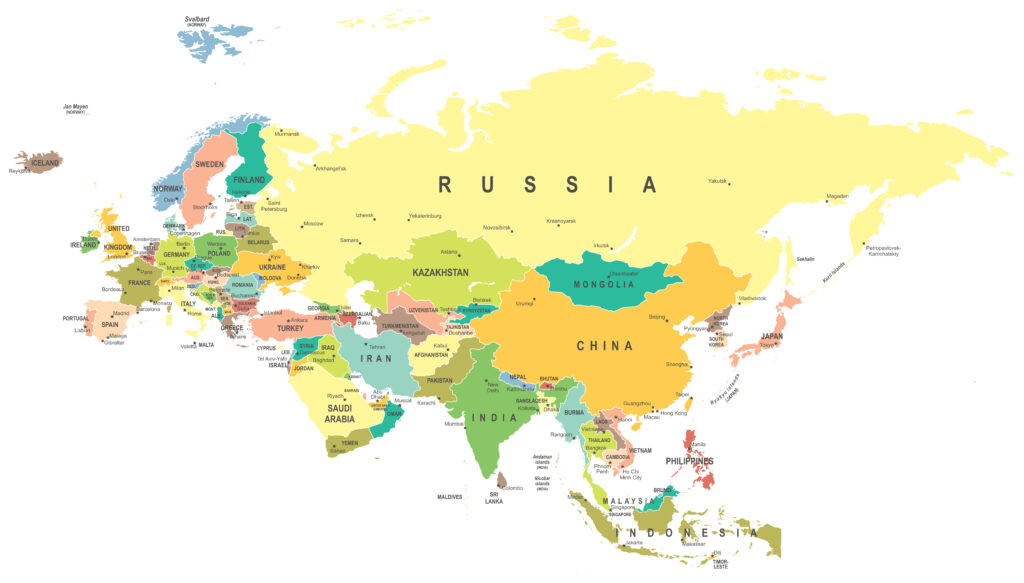

Then, just looking at a map, you can see that the Donbass is a region with a lot of built-up and inhabited areas, which means an advantage for the defender and a reduced speed of progress for the attacker in all circumstances.

Secondly, there is the way our media portray the evolution of the conflict. Ukraine is a huge country and small-scale maps hardly show the differences from one day to another. Moreover, each side has its own perception of the progress of the enemy. If we take the example of the situation on March 25, 2022, we can see that the map of the French daily newspaper Ouest-France (a) shows almost no advance of Russia, as does the Swiss RTS site (b). The map of the Russian website RIAFAN (c) may be propaganda, but if we compare it with the map of the French Military Intelligence Directorate (DRM) (d), we see that the Russian media is probably closer to the truth. All these maps were published on the same day, but the French newspaper and the Swiss state media did not choose to use the DRM map and preferred to use a Ukrainian map. This illustrates that our media work like propaganda outlets.

Thirdly, our “experts” have themselves determined the objectives of the Russian offensive. By claiming that Russia wanted to take over Ukraine and its resources, to take over Kiev in two days, etc., our experts have literally invented and attributed to the Russians objectives that Putin never mentioned. In May 2022, Claude Wild, the Swiss ambassador in Kiev, declared on RTS that the Russians had “lost the battle for Kiev.” But in reality, there was never a “battle for Kiev.” It is obviously easy to claim that the Russians did not reach their objectives—if they never tried to reach them!

Fourthly, the West and Ukraine have created a misleading picture of their adversary. In France, Switzerland and Belgium, none of the military experts on television have any knowledge of military operations and how the Russians conduct theirs. Their “expertise” comes from the rumours from the war in Afghanistan or Syria, which are often merely Western propaganda. These experts have literally falsified the presentation of Russian operations.

Thus, the objectives announced as early as February 24 by Russia were the “demilitarization” and “denazification” of the threat to the populations of Donbass. These objectives are related to the neutralization of capabilities, not the seizure of land or resources. To put it bluntly, in theory, to achieve their goals the Russians do not need to advance—it would be enough if Ukrainians themselves would come and get killed.

In other words, our politicians and media have pushed Ukraine to defend the terrain like in France during the First World War. They pushed Ukrainian troops to defend every square meter of ground in “last stand” situations. Ironically, the West has only made the Russians’ job easier.

In fact, as with the war on terror, Westerners see the enemy as they would like him to be, not as he is. As Sun Tzu said 2,500 years ago, this is the best recipe for losing a war.

One example is the so-called “hybrid war” that Russia is allegedly waging against the West. In June 2014, as the West tried to explain Russia’s (imaginary) intervention in the Donbass conflict, Russia expert Mark Galeotti “revealed” the existence of a doctrine that would illustrate the Russian concept of hybrid warfare. Known as the “Gerasimov Doctrine,” it has never really been defined by the West as to what it consists of and how it could ensure military success. But it is used to explain how Russia wages war in Donbass without sending troops there and why Ukraine consistently loses its battles against the rebels. In 2018, realizing that he was wrong, Galeotti apologized—courageously and intelligently—in an article titled, “I’m Sorry for Creating the Gerasimov Doctrine” published in Foreign Policy magazine.

Despite this, and without knowing what it meant, our media and politicians continued to pretend that Russia was waging a hybrid war against Ukraine and the West. In other words, we imagined a type of war that does not exist and we prepared Ukraine for it. This is also what explains the challenge for Ukraine to have a coherent strategy to counter Russian operations.

The West does not want to see the situation as it really is. The Russian-speaking coalition has launched its offensive with an overall strength inferior to that of the Ukrainians in a ratio of 1-2:1. To be successful when you are outnumbered, you must create local and temporary superiorities by quickly moving your forces on the battlefield.

This is what the Russians call “operational art” (operativnoe iskoustvo). This notion is poorly understood in the West. The term “operational” used in NATO has two translations in Russian: “operative” (which refers to a command level) and “operational” (which defines a condition). It is the art of maneuvering military formations, much like a chess game, in order to defeat a superior opponent.

For example, the operation around Kiev was not intended to “deceive” the Ukrainians (and the West) about their intentions, but to force the Ukrainian army to keep large forces around the capital and thus “pin them down.” In technical terms, this is what is called a “shaping operation.” Contrary to the analysis of some “experts,” it was not a “deception operation,” which would have been conceived very differently and would have involved much larger forces. The aim was to prevent a reinforcement of the main body of the Ukrainian forces in the Donbass.

The main lesson of this war at this stage confirms what we know since the Second World War: the Russians master the operational art.

TP: Questions about Russia’s military raises the obvious question—how good is Ukraine’s military today? And more importantly, why do we not hear so much about the Ukrainian army?

JB: The Ukrainian servicemen are certainly brave soldiers who perform their duty conscientiously and courageously. But my personal experience shows that in almost every crisis, the problem is at the head. The inability to understand the opponent and his logic and to have a clear picture of the actual situation is the main reason for failures.

Since the beginning of the Russian offensive, we can distinguish two ways of conducting the war. On the Ukrainian side, the war is waged in the political and informational spaces, while on the Russian side the war is waged in the physical and operational space. The two sides are not fighting in the same spaces. This is a situation that I described in 2003 in my book, La guerre asymétrique ou la défaite du vainqueur (Asymmetric War, or the Defeat of the Winner). The trouble is that at the end of the day, the reality of the terrain prevails.

On the Russian side, decisions are made by the military, while on the Ukrainian side, Zelensky is omnipresent and the central element in the conduct of the war. He makes operational decisions, apparently often against the military’s advice. This explains the rising tensions between Zelensky and the military. According to Ukrainian media, Zelensky could dismiss General Valery Zoluzhny by appointing him Minister of Defence.

The Ukrainian army has been extensively trained by American, British and Canadian officers since 2014. The trouble is that for over 20 years, Westerners have been fighting armed groups and scattered adversaries and engaged entire armies against individuals. They fight wars at the tactical level and somehow have lost the ability to fight at the strategic and operative levels. This explains partly why Ukraine is waging its war at this level.

But there is a more conceptual dimension. Zelensky and the West see war as a numerical and technological balance of forces. This is why, since 2014, the Ukrainians have never tried to seduce the rebels and they now think that the solution will come from the weapons supplied by the West. The West provided Ukraine with a few dozen M777 guns and HIMARS and MLRS missile launchers, while Ukraine had several thousand equivalent artillery pieces in February. The Russian concept of “correlation of forces,” takes into account many more factors and is more holistic than the Western approach. That is why the Russians are winning.

To comply with ill-considered policies, our media have constructed a virtual reality that gives Russia the bad role. For those who observe the course of the crisis carefully, we could almost say they presented Russia as a “mirror image” of the situation in Ukraine. Thus, when the talk about Ukrainian losses began, Western communication turned to Russian losses (with figures given by Ukraine).

The so-called “counter-offensives” proclaimed by Ukraine and the West in Kharkov and Kherson in April-May were merely “counter-attacks.” The difference between the two is that counter-offensive is an operational notion, while counter-attack is a tactical notion, which is much more limited in scope. These counterattacks were possible because the density of Russian troops in these sectors was then 1 Battle Group (BTG) per 20 km of front. By comparison, in the Donbass sector, which was the primary focus, the Russian coalition had 1-3 BTG per km. As for the great August offensive on Kherson, which was supposed to take over the south of the country, it seems to have been nothing but a myth to maintain Western support.

Today, we see that the claimed Ukrainian successes were in fact failures. The human and material losses that were attributed to Russia were in fact more in line with those of Ukraine. In mid-June, David Arakhamia, Zelensky’s chief negotiator and close adviser, spoke of 200 to 500 deaths per day, and he mentioned casualties (dead, wounded, captured, deserters) of 1,000 men per day. If we add to this the renewed demands for arms by Zelensky, we can see that the idea of a victory for Ukraine appears quite an illusion.

Because Russia’s economy was thought to be comparable to Italy’s, it was assumed that it would be equally vulnerable. Thus, the West—and the Ukrainians—thought that economic sanctions and political isolation of Russia would quickly cause its collapse, without passing through a military defeat. Indeed, this is what we understand from the interview of Oleksei Arestovich, Zelensky’s advisor and spokesman, in March 2019. This also explains why Zelensky did not sound the alarm in early 2022, as he says in his interview with the Washington Post. I think he knew that Russia would respond to the offensive Ukraine was preparing in the Donbass (which is why the bulk of his troops were in that area) and thought that sanctions would quickly lead to Russia’s collapse and defeat. This is what Bruno Le Maire, the French Minister of the Economy, had “predicted.” Clearly, the Westerners have made decisions without knowing their opponent.

As Arestovich said, the idea was that the defeat of Russia would be Ukraine’s entry ticket to NATO. So, the Ukrainians were pushed to prepare an offensive in the Donbass in order to make Russia react, and thus obtain an easy defeat through devastating sanctions. This is cynical and shows how much the West—led by the Americans—has misused Ukraine for its own objectives.

The result is that the Ukrainians did not seek Ukraine’s victory, but Russia’s defeat. This is very different and explains the Western narrative from the first days of the Russian offensive, which prophesied this defeat.

But the reality is that the sanctions did not work as expected, and Ukraine found itself dragged into combats that it had provoked, but for which it was not prepared to fight for so long.

This is why, from the outset, the Western narrative presented a mismatch between media reported and the reality on the ground. This had a perverse effect: it encouraged Ukraine to repeat its mistakes and prevented it from improving its conduct of operations. Under the pretext of fighting Vladimir Putin, we pushed Ukraine to sacrifice thousands of human lives unnecessarily.

From the beginning, it was obvious that the Ukrainians were consistently repeating their mistakes (and even the same mistakes as in 2014-2015), and soldiers were dying on the battlefield. For his part, Volodymyr Zelensky called for more and more sanctions, including the most absurd ones, because he was led to believe that they were decisive.

I am not the only one to have noticed these mistakes, and Western countries could certainly have stopped this disaster. But their leaders, excited by the (fanciful) reports of Russian losses and thinking they were paving the way for regime change, added sanctions to sanctions, turning down any possibility of negotiation. As the French Minister of Economy Bruno Le Maire said, the objective was to provoke the collapse of the Russian economy and make the Russian people suffer. This is a form of state terrorism: the idea is to make the population suffer in order to push it into revolting against its leaders (here, Putin). I am not making this up. This mechanism is detailed by Richard Nephew, head of sanctions at the State Department under Obama and currently Coordinator on Global Anti-Corruption, in his book entitled, The Art of Sanctions. Ironically, this is exactly the same logic that the Islamic State invoked to explain its attacks in France in 2015-2016. France probably does not encourage terrorism—but it does practice it.

The mainstream media do not present the war as it is, but as they would like it to be. This is pure wishful thinking. The apparent public support for the Ukrainian authorities, despite huge losses (some mention 70,000-80,000 fatalities), is achieved by banning the opposition, a ruthless hunt for officials who disagree with the government line, and “mirror” propaganda that attributes to the Russians the same failures as the Ukrainians. All this with the conscious support of the West.

TP: What should we make of the explosion at the Saki airbase in the Crimea?

JB: I do not know the details of the current security situation in Crimea. . We know that before February there were cells of volunteer fighters of Praviy Sektor (a neo-Nazi militia) in Crimea, ready to carry out terrorist-type attacks. Have these cells been neutralized? I don’t know; but one can assume so, since there is apparently very little sabotage activity in Crimea. Having said that, let us not forget that Ukrainians and Russians have lived together for many decades and there are certainly pro-Kiev individuals in the areas taken by the Russians. It is therefore realistic to think that there could be sleeper cells in these areas.

More likely it is a campaign conducted by the Ukrainian security service (SBU) in the territories occupied by the Russian-speaking coalition. This is a terrorist campaign targeting pro-Russian Ukrainian personalities and officials. It follows major changes in the leadership of the SBU, in Kiev, and in the regions, including Lvov, Ternopol since July. It is probably in the context of this same campaign that Darya Dugina was assassinated on August 21. The objective of this new campaign could be to convey the illusion that there is an ongoing resistance in the areas taken by the Russians and thus revive Western aid, which is starting to fatigue.

These sabotage activities do not really have an operational impact and seem more related to a psychological operation. It may be that these are actions like the one on Snake Island at the beginning of May, intended to demonstrate to the international public that Ukraine is acting.

What the incidents in Crimea indirectly show is that the popular resistance claimed by the West in February does not exist. It is most likely the action of Ukrainian and Western (probably British) clandestine operatives. Beyond the tactical actions, this shows the inability of the Ukrainians to activate a significant resistance movement in the areas seized by the Russian-speaking coalition.

TP: Zelensky has famously said, “Crimea is Ukrainian and we will never give it up.” Is this rhetoric, or is there a plan to attack Crimea? Are there Ukrainian operatives inside Crimea?

JB: First of all, Zelensky changes his opinion very often. In March 2022, he made a proposal to Russia, stating that he was ready to discuss a recognition of Russian sovereignty over the peninsula. It was upon the intervention of the European Union and Boris Johnson on 2 April and on 9 April that he withdrew his proposal, despite Russia’s favorable interest.

It is necessary to recall some historical facts. The cession of Crimea to Ukraine in 1954 was never formally validated by the parliaments of the USSR, Russia and Ukraine during the communist era. Moreover, the Crimean people agreed to be subject to the authority of Moscow and no longer of Kiev as early as January 1991. In other words, Crimea was independent from Kiev even before Ukraine became independent from Moscow in December 1991.

In July, Aleksei Reznikov, the Ukrainian Minister of Defense, spoke loudly of a major counter-offensive on Kherson involving one million men to restore Ukraine’s territorial integrity. In reality, Ukraine has not managed to gather the troops, armor and air cover needed for this far-fetched offensive. Sabotage actions in Crimea may be a substitute for this “counter-offensive.” They seem to be more of a communication exercise than a real military action. These actions seem to be aimed rather at reassuring Western countries which are questioning the relevance of their unconditional support to Ukraine.

TP: Would you tell us about the situation around the Zaporizhzhia nuclear facility?

JB: In Energodar, the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant (ZNPP), has been the target of several attacks by artillery, which Ukrainians and Russians attribute to the opposing side.

What we know is that the Russian coalition forces have occupied the ZNPP site since the beginning of March. The objective at that time was to secure the ZNPP quickly, in order to prevent it from being caught up in the fighting and thus avoid a nuclear incident. The Ukrainian personnel who were in charge of it have remained on site and continue to work under the supervision of the Ukrainian company Energoatom and the Ukrainian nuclear safety agency (SNRIU). There is therefore no fighting around the plant.

It is hard to see why the Russians would shell a nuclear plant that is under their control. This allegation is even more peculiar since the Ukrainians themselves state that there are Russian troops in the premises of the site. According to a French “expert,” the Russians would attack the power plant they control to cut off the electricity flowing to Ukraine. Not only would there be simpler ways to cut off the electricity to Ukraine (a switch, perhaps?), but Russia has not stopped the electricity supply to the Ukrainians since March. Moreover, I remind you that Russia has not stopped the flow of natural gas to Ukraine and has continued to pay Ukraine the transit fees for gas to Europe. It is Zelensky who decided to shut down the Soyuz pipeline in May.

Moreover, it should be remembered that the Russians are in an area where the population is generally favorable to them and it is hard to understand why they would take the risk of a nuclear contamination of the region.

In reality, the Ukrainians have more credible motives than the Russians that may explain such attacks against the ZNPP. , which are not mutually exclusive: an alternative to the big counter-offensive on Kherson, which they are not able to implement, and to prevent the planned referendums in the region. Further, Zelensky’s calls for demilitarizing the area of the power plant and even returning it to Ukraine would be a political and operational success for him. One might even imagine that they seek to deliberately provoke a nuclear incident in order to create a “no man’s land” and thus render the area unusable for the Russians.

By bombing the plant, Ukraine could also be trying to pressure the West to intervene in the conflict, under the pretext that Russia is seeking to disconnect the plant from the Ukrainian power grid before the fall. This suicidal behavior—as stated by UN Secretary General António Guterres—would be in line with the war waged by Ukraine since 2014.

There is strong evidence that the attacks on Energodar are Ukrainian. The fragments of projectiles fired at the site from the other side of the Dnieper are of Western origin. It seems that they come from British BRIMSTONE missiles, which are precision missiles, whose use is monitored by the British. Apparently, the West is aware of the Ukrainian attacks on the ZNPP. This might explain why Ukraine is not very supportive of an international commission of inquiry and why Western countries are putting unrealistic conditions for sending investigators from the IAEA, an agency that has not shown much integrity so far.

TP: It is reported that Zelensky is freeing criminals to fight in this war? Does this mean that Ukraine’s army is not as strong as commonly assumed?

JB: Zelensky faces the same problem as the authorities that emerged from Euromaidan in 2014. At that time, the military did not want to fight because they did not want to confront their Russian-speaking compatriots. According to a report by the British Home Office, reservists overwhelmingly refuse to attend recruitment sessions . In October-November 2017, 70% of conscripts do not show up for recall . Suicide has become a problem. According to the chief Ukrainian military prosecutor Anatoly Matios, after four years of war in the Donbass, 615 servicemen had committed suicide. Desertions have increased and reached up to 30% of the forces in certain operational areas, often in favor of the rebels.

For this reason, it became necessary to integrate more motivated, highly politicized, ultra-nationalistic and fanatical fighters into the armed forces to fight in the Donbass. Many of them are neo-Nazis. It is to eliminate these fanatical fighters that Vladimir Putin has mentioned the objective of “denazification.”

Today, the problem is slightly different. The Russians have attacked Ukraine and the Ukrainian soldiers are not a priori opposed to fighting them. But they realize that the orders they receive are not consistent with the situation on the battlefield. They understood that the decisions affecting them are not linked to military factors, but to political considerations. Ukrainian units are mutinying en masse and are increasingly refusing to fight. They say they feel abandoned by their commanders and that they are given missions without the necessary resources to execute them.

That’s why it becomes necessary to send men who are ready for anything. Because they are condemned, they can be kept under pressure. This is the same principle as Marshal Konstantin Rokossovki, who was sentenced to death by Stalin, but was released from prison in 1941 to fight against the Germans. His death sentence was lifted only after Stalin’s death in 1956.

In order to overshadow the use of criminals in the armed forces, the Russians are accused of doing the same thing. The Ukrainians and the Westerners consistently use “mirror” propaganda. As in all recent conflicts, Western influence has not led to a moralization of the conflict.

TP: Everyone speaks of how corrupt Putin is? But what about Zelensky? Is he the “heroic saint” that we are all told to admire?

JB: In October 2021, the Pandora Papers showed that Ukraine and Zelensky were the most corrupt in Europe and practiced tax evasion on a large scale. Interestingly, these documents were apparently published with the help of an American intelligence agency, and Vladimir Putin is not mentioned. More precisely, the documents mention individuals ” associated ” with him, who are said to have links with undisclosed assets, which could belong to a woman, who is believed to have had a child with him.

Yet, when our media are reporting on these documents, they routinely put a picture of Vladimir Putin, but not of Volodymyr Zelensky.

I am not in a position to assess how corrupt Zelensky is. But there is no doubt that the Ukrainian society and its governance are. I contributed modestly to a NATO “Building Integrity” program in Ukraine and discovered that none of the contributing countries had any illusions about its effectiveness, and all saw the program as a kind of “window dressing” to justify Western support.

It is unlikely that the billions paid by the West to Ukraine will reach the Ukrainian people. A recent CBS News report stated that only 30-40% of the weapons supplied by the West make it to the battlefield. The rest enriches mafias and other corrupt people. Apparently, some high-tech Western weapons have been sold to the Russians, such as the French CAESAR system and presumably the American HIMARS. The CBS News report was censored to avoid undermining Western aid, but the fact remains that the US refused to supply MQ-1C drones to Ukraine for this reason.

Ukraine is a rich country, yet today it is the only country in the former USSR with a lower GDP than it had at the collapse of the Soviet Union. The problem is therefore not Zelensky himself, but the whole system, which is deeply corrupted, and which the West maintains for the sole purpose of fighting Russia.

Zelensky was elected in April 2019 on the program of reaching an agreement with Russia. But nobody let him carry out his program. The Germans and the French deliberately prevented him from implementing the Minsk agreements. The transcript of the telephone conversation of 20 February 2022 between Emmanuel Macron and Vladimir Putin shows that France deliberately kept Ukraine away from the solution. Moreover, in Ukraine, far right and neo-Nazi political forces have publicly threatened him with death. Dmitry Yarosh, commander of the Ukrainian Volunteer Army, declared in May 2019 that Zelensky would be hanged if he carried out his program. In other words, Zelensky is trapped between his idea of reaching an agreement with Russia and the demands of the West. Moreover, the West realizes that its strategy of war through sanctions has failed. As the economic and social problems increase, the West will find it harder to back down without losing face. A way out for Britain, the US, the EU, or France would be to remove Zelensky. That is why, with the deteriorating situation in Ukraine, I think Zelensky starts to realize that his life is threatened.

At the end of the day, Zelensky is a poor guy, because his best enemies are those on whom he depends: the Western world.

TP: There are many videos (gruesome ones) on social media of Ukrainian soldiers engaging in serious war crimes? Why is there a “blind spot” in the West for such atrocities?

JB: First of all, we must be clear: in every war, every belligerent commit war crimes. Military personnel who deliberately commit such crimes dishonor their uniform and must be punished.

The problem arises when war crimes are part of a plan or result from orders given by the higher command. This was the case when the Netherlands let its military allow the Srebrenica massacre in 1995; the torture in Afghanistan by Canadian and British troops, not to mention the countless violations of international humanitarian law by the United States in Afghanistan, Iraq, Guantanamo and elsewhere with the complicity of Poland, Lithuania or Estonia. If these are Western values, then Ukraine is in the right school.

In Ukraine, political crime has become commonplace, with the complicity of the West. Thus, those who are in favor of a negotiation are eliminated. This is the case of Denis Kireyev, one of the Ukrainian negotiators, assassinated on March 5 by the Ukrainian security service (SBU) because he was considered too favorable to Russia and as a traitor. The same thing happened to Dmitry Demyanenko, an officer of the SBU, who was assassinated on March 10, also because he was too favorable to an agreement with Russia. Remember that this is a country that considers that receiving or giving Russian humanitarian aid is “collaborationism.”

On 16 March 2022, a journalist on TV channel Ukraine 24 referred to the Nazi war criminal Adolf Eichmann and called for the massacre of Russian-speaking children. On 21 March, the military doctor Gennadiy Druzenko declared on the same channel that he had ordered his doctors to castrate Russian prisoners of war. On social networks, these statements quickly became propaganda for the Russians and the two Ukrainians apologized for having said so, but not for the substance. Ukrainian crimes were beginning to be revealed on social networks, and on 27 March Zelensky feared that this would jeopardize Western support. This was followed—rather opportunely—by the Bucha massacre on 3 April, the circumstances of which remain unclear.

Britain, which then had the chairmanship of the UN Security Council, refused three times the Russian request to set up an international commission of enquiry into the crimes of Bucha. Ukrainian socialist MP Ilya Kiva revealed on Telegram that the Bucha tragedy was planned by the British MI6 special services and implemented by the SBU.

The fundamental problem is that the Ukrainians have replaced the “operational art” with brutality. Since 2014, in order to fight the autonomists, the Ukrainian government has never tried to apply strategies based on “hearts & minds,” which the British used in the 1950s-1960s in South-East Asia, which were much less brutal but much more effective and long-lasting. Kiev preferred to conduct an Anti-Terrorist Operation (ATO) in the Donbass and to use the same strategies as the Americans in Iraq and Afghanistan. Fighting terrorists authorizes all kinds of brutality. It is the lack of a holistic approach to the conflict that led to the failure of the West in Afghanistan, Iraq and Mali.

Counter-Insurgency Operation (COIN) requires a more sophisticated and holistic approach. But NATO is incapable of developing such strategies as I have seen first-hand in Afghanistan. The war in Donbass has been brutal for 8 years and has resulted in the death of 10,000 Ukrainian citizens plus 4,000 Ukrainian military personnel. By comparison, in 30 years, the conflict in Northern Ireland resulted in 3,700 deaths. To justify this brutality, the Ukrainians had to invent the myth of a Russian intervention in Donbass.

The problem is that the philosophy of the new Maidan leaders was to have a racially pure Ukraine. In other words, the unity of the Ukrainian people was not to be achieved through the integration of communities, but through the exclusion of communities of “inferior races.” An idea that would no doubt have pleased the grandfathers of Ursula von der Leyen and Chrystia Freeland! This explains why Ukrainians have little empathy for the country’s Russian, Magyar and Romanian-speaking minorities. This in turn explains why Hungary and Romania do not want their territories to be used for the supply of arms to Ukraine.

This is why shooting at their own citizens to intimidate them is not a problem for the Ukrainians. This explains the spraying of thousands of PFM-1 (“butterfly”) anti-personnel mines, which look like toys, on the Russian-speaking city of Donetsk in July 2022. This type of mine is used by a defender, not an attacker in its main area of operation. Moreover, in this area, the Donbass militias are fighting “at home,” with populations they know personally.

I think that war crimes have been committed on both sides, but that their media coverage has been very different. Our media have reported extensively about crimes (true or false) attributed to Russia. On the other hand, they have been extremely silent about Ukrainian crimes. We do not know the whole truth about the Bucha massacre, but the available evidence supports the hypothesis that Ukraine staged the event to cover up its own crimes. By keeping these crimes quiet, our media have been complicit with them and have created a sense of impunity that has encouraged the Ukrainians to commit further crimes.

TP: Latvia wants the West (America) to designate Russia a “terrorist state.” What do you make of this? Does this mean that the war is actually over, and Russia has won?

JB: The Estonian and Latvian demands are in response to Zelensky’s call to designate Russia as a terrorist state. Interestingly, they come at the same time a Ukrainian terrorist campaign is being unleashed in Crimea, the occupied zone of Ukraine and the rest of Russian territory. It is also interesting that Estonia was apparently complicit in the attack on Darya Dugina in August 2022.

It seems that Ukrainians communicate in a mirror image of the crimes they commit or the problems they have, in order to hide them. For example, in late May 2022, as the Azovstal surrender in Mariupol showed neo-Nazi fighters, they began to allege that there are neo-Nazis in the Russian army. In August 2022, when Kiev was carrying out actions of a terrorist nature against the Energodar power plant in Crimea and on Russian territory, Zelensky called for Russia to be considered a terrorist state.

In fact, Zelensky continues to believe that he can only solve his problem by defeating Russia and that this defeat depends on sanctions against Russia. Declaring Russia a terrorist state would lead to further isolation. That is why he is making this appeal. This shows that the label “terrorist” is more political than operational, and that those who make such proposals do not have a very clear vision of the problem. The problem is that it has implications for international relations. This is why the US State Department is concerned that Zelensky’s request will be implemented by Congress.

TP: One of the sadder outcomes of this Ukraine-Russia conflict is how the West has shown the worst of itself. Where do you think we will go from here? More of the same, or will there be changes that will have to be made in regards to NATO, neutral countries which are no longer neutral, and the way the West seeks to “govern” the world?

JB: This crisis reveals several things. First, that NATO and the European Union are only instruments of US foreign policy. These institutions no longer act in the interests of their members, but in the interests of the US. The sanctions adopted under American pressure are backfiring on Europe, which is the big loser in this whole crisis: it suffers its own sanctions and has to deal with the tensions resulting from its own decisions.

The decisions taken by Western governments reveal a generation of leaders who are young and inexperienced (such as Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin); ignorant, yet thinking they are smart (such as French President Emmanuel Macron); doctrinaire (such as European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen); and fanatical (such as the leaders of the Baltic States). They all share some of the same weaknesses, not least of which is their inability to manage a complex crisis.

When the head is unable to understand the complexity of a crisis, we respond with guts and dogmatism. This is what we see happening in Europe. The Eastern European countries, especially the Baltic States and Poland, have shown themselves to be loyal servants of American policy. They have also shown immature, confrontational, and short-sighted governance. These are countries that have never integrated Western values, that continue to celebrate the forces of the Third Reich and discriminate against their own Russian-speaking population.

I am not even mentioning the European Union, which has been vehemently opposed to any diplomatic solution and has only added fuel to the fire.

The more you are involved in a conflict, the more you are involved in its outcome. If you win, all is well. But if the conflict is a failure, you will bear the burden. This is what has happened to the United States in recent conflicts and what is happening in Ukraine. The defeat of Ukraine is becoming the defeat of the West.

Another big loser in this conflict is clearly Switzerland. Its neutral status has suddenly lost all credibility. Early August, Switzerland and Ukraine concluded an agreement that would allow the Swiss embassy in Moscow to offer protection to Ukrainian citizens in Russia. However, in order to enter into force, it has to be recognized by Russia. Quite logically, Russia refused and declared that “Switzerland had unfortunately lost its status as a neutral state and could not act as an intermediary or representative.”

This is a very serious development because neutrality is not simply a unilateral declaration. It must be accepted and recognized by all to be effective. Yet Switzerland not only aligned itself with the Western countries but was even more extreme than them. It can be said that in a few weeks, Switzerland has ruined a policy that has been recognized for almost 170 years. This is a problem for Switzerland, but it may also be a problem for other countries. A neutral state can offer a way out of a crisis. Today, Western countries are looking for a way out that would allow them to get closer to Russia in the perspective of an energy crisis without losing face. Turkey has taken on this role, but it is limited, as it is part of NATO.

The West has created an Iron Curtain 2.0 that will affect international relations for years to come. The West’s lack of strategic vision is astonishing. While NATO is aligning itself with US foreign policy and reorienting itself towards China, Western strategy has only strengthened the Moscow-Beijing axis.

TP: What do you think this war ultimately means for Europe, the US and China?

JB: In order to answer this question, we first must answer another question: “Why is this conflict more condemnable and sanctionable than previous conflicts started by the West?”

After the disasters of Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya and Mali, the rest of the world expected the West to help resolve this crisis with common sense. The West responded in exactly the opposite way to these expectations. Not only has no one been able to explain why this conflict was more reprehensible than previous ones, but the difference in treatment between Russia and the United States has shown that more importance is attached to the aggressor than to the victims. Efforts to bring about the collapse of Russia contrast with the total impunity of countries that have lied to the UN Security Council, practiced torture, caused the deaths of over a million people and created 37 million refugees.

This difference in treatment went unnoticed in the West. But the “rest of the world” has understood that we have moved from a “law-based international order” to a “rules-based international order” determined by the West.

On a more material level, the confiscation of Venezuelan gold by the British in 2020, of Afghanistan’s sovereign funds in 2021, and then of Russia’s sovereign funds in 2022 by the US, has raised the mistrust of the West’s allies. This shows that the non-Western world is no longer protected by law and depends on the goodwill of the West.

This conflict is probably the starting point for a new world order. The world is not going to change all at once, but the conflict has raised the attention of the rest of the world. For when we say that the “international community” condemns Russia, we are in fact talking about 18% of the world’s population.

Some actors traditionally close to the West are gradually moving away from it. On 15 July 2022, Joe Biden visited Mohammed bin Salman (MbS) with two objectives: to prevent Saudi Arabia from moving closer to Russia and China, and to ask him to increase its oil production. But four days earlier, MbS made an official request to become a member of the BRICS, and a week later, on 21 July, MbS called Vladimir Putin to confirm that he would stand by the OPEC+ decision. In other words: no oil production increase. It was a slap in the face of the West and of its most powerful representative.

Saudi Arabia has now decided to accept Chinese currency as payment for its oil. This is a major event, which tends to indicate a loss of confidence in the dollar. The consequences are potentially huge. The petrodollar was established by the US in the 1970s to finance its deficit. By forcing other countries to buy dollars, it allows the US to print dollars without being caught in an inflationary loop. Thanks to the petrodollar, the US economy—which is essentially a consumer economy—is supported by the economies of other countries around the world. The demise of the petrodollar could have disastrous consequences for the US economy, as former Republican Senator Ron Paul puts it.

In addition, the sanctions have brought China and Russia, both targeted by the West, closer together. This has accelerated the formation of a Eurasian bloc and strengthened the position of both countries in the world. India, which the US has scorned as a “second-class” partner of the “Quad,” has moved closer to Russia and China, despite disputes with the latter.

Today, China is the main provider of infrastructure in the Third World. In particular, its way of interacting with African countries is more in line with the expectations of these countries. Collaboration with former colonial powers such as France and American imperialist paternalism are no longer welcome. For example, the Central African Republic and Mali have asked France to leave their countries and have turned to Russia.

At the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) summit, the US proudly announced a $150 million contribution to “strengthen its position in the broader geopolitical competition with China.” But in November 2021, President Xi Jinping offered $1.5 billion to the same countries to fight the pandemic and promote economic recovery. By using its money to wage war, the US has no money left to forge and consolidate alliances.

The West’s loss of influence stems from the fact that it continues to treat the “rest of the world” like “little children” and neglects the usefulness of good diplomacy.

The war in Ukraine is not the trigger for these phenomena, which started a few years ago, but it is most certainly an eye-opener and accelerator.

TP: The western media has been pushing that Putin may be seriously ill. If Putin suddenly dies, would this make any difference at all to the war?

JB: It seems that Vladimir Putin is a unique medical case in the world: he has stomach cancer, leukemia, an unknown but incurable and terminal phase disease, and is reportedly already dead. Yet in July 2022, at the Aspen Security Forum, CIA Director William Burns said that Putin was “too healthy” and that there was “no information to suggest that he is in poor health.” This shows how those who claim to be journalists work!

This is wishful thinking and, on the higher end of the spectrum, it echoes the calls for terrorism and the physical elimination of Vladimir Putin.

The West has personalized Russian politics through Putin, because he is the one who promoted the reconstruction of Russia after the Yeltsin years. Americans like to be champions when there are no competitors and see others as enemies. This is the case with Germany, Europe, Russia and China.

But our “experts” know little about Russian politics. For in reality, Vladimir Putin is more of a “dove” in the Russian political landscape. Given the climate that we have created with Russia, it would not be impossible that his disappearance would lead to the emergence of more aggressive forces. We should not forget that countries like Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland or Georgia have never developed European democratic values. They still have discriminatory policies towards their ethnic Russians that are far from European values, and they behave like immature agents provocateurs. I think that if Putin were to disappear for some reason, the conflicts with these countries would take on a new dimension.

TP: How unified is Russia presently? Has the war created a more serious opposition than what previously existed within Russia?

JB: No, on the contrary. The American and European leaders have a poor understanding of their enemy: the Russian people are very patriotic and cohesive. Western obsession to ” punish ” the Russian people has only brought them closer to their leaders. In fact, by seeking to divide Russian society in an effort to overthrow the government, Western sanctions—including the dumbest ones—have confirmed what the Kremlin has been saying for years: that the West has a profound hatred of Russians. What was once said to be a lie is now confirmed in Russian opinion. The consequence is that the people’s trust in the government has grown stronger.

The approval ratings given by the Levada Centre (considered by the Russian authorities as a “foreign agent”) show that public opinion has tightened around Vladimir Putin and the Russian government. In January 2022, Vladimir Putin’s approval rating was 69% and the government’s was 53%. Today, Putin’s approval rating has been stable at around 83% since March, and the government’s is at 71%. In January, 29% did not approve of Vladimir Putin’s decisions, in July it was only 15%.

According to the Levada Centre, even the Russian operation in Ukraine enjoys a majority of favorable opinions. In March, 81% of Russians were in favor of the operation; this figure dropped to 74%, probably due to the impact of sanctions at the end of March, and then it went back up. In July 2022, the operation had 76% popular support.

The problem is that our journalists have neither culture nor journalistic discipline and they replace them with their own beliefs. It is a form of conspiracy that aims to create a false reality based on what one believes and not on the facts. For example, few know (or want to know) that Aleksey Navalny said he would not return Crimea to Ukraine. The West’s actions have completely wiped out the opposition, not because of “Putin’s repression,” but because in Russia, resistance to foreign interference and the West’s deep contempt for Russians is a bipartisan cause. Exactly like the hatred of Russians in the West. This is why personalities like Aleksey Navalny, who never had a very high popularity, have completely disappeared from the popular media landscape.

Moreover, even if the sanctions have had a negative impact on the Russian economy, the way the government has handled things since 2014 shows a great mastery of economic mechanisms and a great realism in assessing the situation. There is a rise in prices in Russia, but it is much lower than in Europe, and while Western economies are raising their key interest rates, Russia is lowering its own.

The Russian journalist Marina Ovsyannikova has been exemplified as an expression of the opposition in Russia. Her case is interesting because, as usual, we do not say everything.

On 14 March 2022, she provoked international applause by interrupting the Russian First Channel news program with a poster calling for ending the war in Ukraine. She was arrested and fined $280.

In May, the German newspaper Die Welt offered her a job in Germany, but in Berlin, pro-Ukrainian activists demonstrated to get the newspaper to end its collaboration with her. The media outlet Politico even suggested that she might be an agent of the Kremlin!

As a result, in June 2022, she left Germany to live in Odessa, her hometown. But instead of being grateful, the Ukrainians put her on the Mirotvorets blacklist where she is accused of treason, “participation in the Kremlin’s special information and propaganda operations” and “complicity with the invaders.”

The Mirotvorets website is a “hit list” for politicians, journalists or personalities who do not share the opinion of the Ukrainian government. Several of the people on the list have been murdered. In October 2019, the UN requested the closure of the site, but this was refused by the Rada. It should be noted that none of our mainstream media has condemned this practice, which is very far from the values they claim to defend. In other words, our media support these practices that used to be attributed to South American regimes.

Ovsyannikova then returned to Russia, where she demonstrated against the war, calling Putin a “killer,” and was arrested by the police and placed under house arrest for three months. At this point, our media protested.

It is worth noting that Russian journalist Darya Dugina, the victim of a bomb attack in Moscow on 21 August 2022, was on the Mirotvorets list and her file was marked “liquidated.” Of course, no Western media mentioned that she was targeted by the Mirotvorets website, which is considered to be linked to the SBU, as this would tend to support Russia’s accusations.

German journalist Alina Lipp, whose revelations about Ukrainian and Western crimes in the Donbass are disturbing, has been placed on the website Mirotvorets. Moreover, Alina Lipp was sentenced in absentia to three years in prison by a German court for claiming that Russian troops had “liberated” areas in Ukraine and thus “glorified criminal activities.” As can be seen, the German authorities are functioning like the neo-Nazi elements in Ukraine. Today’s politicians are a credit to their grandparents!

One can conclude that even if there are some people who oppose the war, Russian public opinion is overwhelmingly behind its government. Western sanctions have only strengthened the credibility of the Russian president.

Ultimately, my point is not to take the same approach as our media and replace the hatred of Russia with that of Ukraine. On the contrary, it is to show that the world is not either black or white and that Western countries have taken the situation too far. Those who are compassionate about Ukraine should have pushed our governments to implement the agreed political solutions in 2014 and 2015. They haven’t done anything and are now pushing Ukraine to fight. But we are no longer in 2021. Today, we have to accept the consequences of our non-decisions and help Ukraine to recover. But this must not be done at the expense of its Russian-speaking population, as we have done until now, but with the Russian-speaking people, in an inclusive manner. If I look at the media in France, Switzerland and Belgium, we are still very far from the goal.

TP: Thank you so very much, Mr. Baud, for this most enlightening discussion.

I’m aware that there’s a great deal of interpretation involved in some of these write-ups on Russian public opinion polls and surveys, but I do think it’s important to pay attention to measures of Russian opinion and this is what can be found right now in English. – Natylie

By Denis Volkov and Andrei Kolesnikov, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 9/7/22

When Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine on February 24, Western governments, including the United States, immediately condemned what they described as “Vladimir Putin’s war.”1 Surely, this formulation was no accident. It was aimed, first and foremost, at drawing a distinction between the actions of the Kremlin and the attitudes of ordinary Russians. There was optimism that ordinary Russians would not countenance a war against a neighboring country.2 But hopes of Russian grassroots opposition to the war were swiftly dashed. Indeed, public opinion polls have consistently shown overwhelming support (70 percent or higher) for what Moscow calls its “special military operation” in Ukraine. Contrary to expectations, Putin’s popularity has also seen a boost, similar to what happened in the immediate wake of the 2014 annexation of Crimea.

Partly in response to these indicators, figures like Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy have called for a visa ban for all Russian passport holders, with an exception for people whose safety is at risk or who are vulnerable to political persecution.3 According to Zelenskyy, “[T]he most important sanctions are to close the borders—because the Russians are taking away someone else’s land” and Russians should “live in their own world until they change their philosophy.” He added, “The population picked this government and they’re not fighting it, not arguing with it, not shouting at it.” Such sentiments are echoed in calls by some European politicians, such as Finnish Prime Minister Sanna Marin, for an EU ban on tourist visas. “It’s not right that at the same time as Russia is waging an aggressive, brutal war of aggression in Europe, Russians can live a normal life, travel in Europe, be tourists. It’s not right,” Marin said in mid-August.4

At the same time, a careful reading of popular Russian attitudes toward the war reveals important nuances that all too often are overlooked. First and foremost is the fact that rather than consolidating Russian society, the conflict has exacerbated existing divisions on a diverse array of issues, including support for the regime. Put another way, the impression that Putin now has the full support of the Russian public is simply incorrect. A more careful reading of sociological data, including conversations with focus group participants and quantitative research, presents a far more complex picture of Russian society.

Note: This paper is based on sociological research and opinion polling carried out across Russia by the Levada Center from February to August 2022, as well as on the findings of eight Levada-convened focus groups that were held from March to May 2022 in Moscow and in three regional centers.

The general picture of public opinion in Russia can be understood in rather simple terms. All across Russia since February 24, old friends have fallen out; parents and children are no longer on speaking terms; long-married couples no longer trust each another; and teachers and students are denouncing each other. Opinions are becoming polarized. Over time, polarized opinions are becoming radicalized. All of that points to growing conflict within Russian society.

Opinion polls consistently show that the majority of respondents support the actions of the Russian Armed Forces in Ukraine. The scale of that support changed little over the first four months of the war.5 But the collection of people who express support for what Moscow calls the “special operation” and for Putin himself is not at all homogenous. (As a rule, Putin supporters tend to support the military campaign.) In June 2022, 47 percent of Russians “definitely supported” the actions of the Russian military, while another 28 percent said they “mostly supported” them.

The former can be put into the category of assured or unconditional support. The judgment of these respondents is the most dogmatic: they are more willing to portray the war as what they call a “preemptive blow,” “an unavoidable measure,” or a form of “defense against [the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO)].” These people tend not to question news reports or narratives that are the bread and butter of Russian state media coverage of the war. They express the highest level of support for Putin and a sense of pride over what is happening in Ukraine. In focus group discussions, they pointedly call what is happening in Ukraine “the special operation.” This term makes sense to them because, as various participants outlined: “It’s not like we are taking anything [that isn’t ours]”; “We’re liberating [Ukraine] from Nazis and fascists”; or “That’s what Vladimir Vladimirovich [Putin] called it, and I trust him.”

In the second group, that is, those who “mostly support” Russia’s actions in Ukraine, the level of support is less resolute. There is more doubt over whether what is going on is right or not and the basis for the Kremlin’s actions. Compared with the group offering unconditional support, people in the second group were twice as likely to express feelings of anxiety, fear, and horror about what is going on. They are also far less likely to express pride. For them, the “special operation” is motivated above all by the desire to protect what Russians describe as Ukraine’s Russian-speaking population. Support for the Russian government’s actions is somewhat lower in this group. The convictions of this group are generally less clearly defined, and they are inclined to simply follow the dominant public opinion and official line. It’s likely that some of these respondents say that they support Russian soldiers out of fear of adverse consequences for themselves. But the number of such individuals should not be exaggerated (see figure 1).

Respondents’ motivations for supporting the “special operation” are quite diverse. In the focus groups there were expressions of jingoistic aggression (mostly from men aged 45–50) such as: “Russia has been fighting since the moment it was founded . . . We watched and we waited for how many years? Eight! And why, what for? . . . It’s better to strike first and assert your independence.” Other participants said, “War is the locomotive of history. We have never invaded anyone; we’ve only ever defended our borders. Why didn’t we do it eight years ago? It wasn’t the right time!” Some respondents, especially women and younger people, engaged in a form of self-persuasion, claiming, for example: “There was no choice,” or “No, you can’t be in favor of war. Our soldiers are being killed there, and Ukrainian soldiers too, and civilians, and children. But what other choice was there? Who can say what other choice there was? Negotiate with them? It was too late!”

Another widespread form of support came from people who are largely indifferent to the situation but who support the government’s actions because they believe the government knows best. Members of this grouping said things like: “The people who are worried are those who have relatives and loved ones [in Ukraine]. For everyone else, who doesn’t have anyone there, they see it as normal.” “I prefer to remain neutral, because I’m not a politician or a soldier and I don’t know what’s really happening.” “I’m a pensioner, we don’t have any say in things . . . I hope it will all be over soon and there will be peace.”

For such people, the least uncomfortable option is to join the mainstream point of view, since that doesn’t force them to think for themselves. It’s not comfortable for such respondents to portray themselves as being outside the realm of the country’s dominant thinking on current affairs. That attitude, in turn, fosters a tendency to block out negative information and difficult news stories. To this group, everything that is being reported about murder, destruction, and looting must be a provocation by the Ukrainians, fake news, or exaggerated information. Such respondents are ready to believe that Putin really didn’t have any other option but to launch a “special operation” to head off an attack on Russia itself.

This sort of conformism does leave room for a certain degree of doubt, but people’s desire to remain in their psychological comfort zone prevails: Russians can’t be on the bad side; they can only be on the good side.

Another aspect of this kind of passive conformism is a predetermined submission to decisions taken by one’s superiors. The type of obedience is dictated not only by passivity, but also by the fear of being fired or even repressed. This may not be the only reason for a respondent’s stated position; after all, there are usually diverse factors at play, but fear is sometimes one of them.

Among the active conformists, there were respondents who were prepared to get up off the sofa and take part in the war themselves. But they were certainly the minority, and often, that participation consisted of denouncing those whom Putin calls national traitors or a fifth column. Such attitudes have become a widespread phenomenon.

The high levels of support for the actions of the Russian military and the surge in approval ratings for the Russian leadership have provoked frequent discussions inside Russia and abroad over the reliability of Russian polls. Many critics argue that pressure on dissent and the introduction of new criminal penalties for charges of “discrediting the armed forces” and other offenses mean that people are more scared and less willing to take part in opinion polls than they may have once been. However, research by the Levada Center to measure the response rate (as per the recommendations of the American Association for Public Opinion Research) does not back up this hypothesis.6 The frequency of responses, communication, and refusal to respond to Levada Center polls are broadly similar to what they were back in January 2021.7 In other words, Levada experts have not found corroborating evidence that Russian respondents have become more reluctant to answer sociologists’ questions since the start of the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The authors are, of course, mindful that the general atmosphere in Russia has grown increasingly repressive over the past decade. Either way, additional research does not back up assertions that people who do not approve of the country’s leadership are more likely to refuse to take part in a poll or that polls only represent people who are prepared to engage and answer questions.8

As for polling experiments that appear to show a lower level of support for the “special operation,”9 the results cannot always be interpreted unambiguously. Researchers who carried out a series of similar experiments looking at mass support for Putin in Russia from 2015 to 2021 warn against the unequivocal interpretation of their results.10

It’s also worth noting that the overall patterns of people’s attitudes to what is happening today are entirely in keeping with the results of polls carried out at the end of 2021 and start of 2022.11 By the start of February, two thirds of the public already supported the Russian regime and its Ukraine policy in one way or another. That support grew as the conflict escalated, with most Russians laying the blame for that escalation on the West. The portions of Russian society that expressed support or opposition were more or less clearly formed, and their composition has not changed significantly. It’s also worthwhile recalling that in 2014, many observers also refused to believe public opinion polls showing high figures of support for the Russian political regime following the annexation of Crimea.12 Over time, the expression “the post-Crimea consensus” became commonplace in analysis about post-2014 shifts in Russian public opinion. Few experts today dispute the existence of such a shift.

There are two key beliefs that allow respondents to remain convinced that the Russian leadership and military are taking the right action: first, that the Russian-speaking population in Ukraine was under threat and second, that responsibility for what is happening lies entirely with Russia’s adversaries. The majority of those who support the “special operation” explain their position in terms of protecting the Russian-speaking population of Ukraine’s Donbas region. A deadly threat to “our people,” “compatriots,” “brothers,” “Russian-speakers,” and “Russians” is reason enough in the eyes of the majority to justify military intervention in a neighboring country, even though the prevailing wisdom in Russian society under normal circumstances would be not to interfere. In such circumstances, the extreme nature of the situation seems to have justified or even required actions that in normal life would seem impossible and unacceptable. Eight years ago, the majority of respondents justified the annexation of Crimea by Russia and support for separatist fighters in the Donbas in a similar way.13

The readiness of Russian public opinion for such measures to be taken in an extreme situation was already being observed at the end of 2021 and start of 2022, when respondents were increasingly saying, “We don’t want war, but we’re being dragged into one,” or “We’re being provoked: we’ll have to respond and help the Donbas.”14

Another key source of support for the Russian military is the conviction of most Russians that the United States and NATO are responsible for escalating the conflict in the Donbas. Even in mid-February 2022, 60 percent of respondents expressed this belief, a number that was up 10 percentage points from November 2021.15

Only a very small percentage of respondents were prepared to blame the Russian side. Most focus group respondents, especially among the older generation, had no doubt that the West, led by the United States, had long been trying to bring Russia to its knees and surround it with military bases. Some said: “I don’t want there to be a war, but it can’t be avoided because the United States has come right up to Russia.” “The world has forgotten that in recent years, the United States has bombed more than twenty countries: for some reason it’s Russia that’s the bad guy and the aggressor.” “America does what it likes regardless of what others think; it drops bombs wherever it likes.” And, “A fight was inevitable. They planned to send Ukrainian troops, with massive support from NATO countries, into the territory of the DNR and LNR [Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics] and possibly, in [the] future, even into Russian territory.”

Currently, about 20 percent of Russians say they do not agree with Russia’s actions in Ukraine, up from 14 percent in March. These respondents refer to what is happening as “war” and “Russian aggression.” They are more likely to be young, residents of Moscow or other large cities, and consumers of news from the internet. At the same time, people in this category (similar to the first two categories discussed) were still more likely than not to support the “special operation.” The only category of people in which the majority opposed the “operation” were those who are opposition-minded in general and, specifically, do not approve of the actions of Putin, the Russian government, or the State Duma. This same section of Russian society voted against the constitutional amendments in 2020, supported anti-Putin opposition figures, and attended anti-regime protests in early 2021. They are also more likely to have vacationed in Europe or to hold more positive views of the West in general.

When explaining their position, such people said first and foremost that it was unacceptable that people were dying.16 People in the focus groups said: “Many innocent civilians are dying, and I don’t believe that’s right.” “I can’t help but be moved by other people’s grief . . . I’m a citizen of the country that is, as they say, carrying out the special operation, and I am an unwilling accomplice.” “I feel sorry for the children.” And “It’s impossible to support war.”

Another reason often cited for opposing events in Ukraine was the negative socioeconomic impact in Russia. Respondents noted: “People are losing their jobs . . . Sanctions have been introduced, [and] the economy is collapsing.” “Everything we had dreamed of came crashing down in one moment. Our entire lives, everything we had fought for, all of our plans . . . Prices are increasing. You can’t buy dollars, or the goods we are accustomed to.” And “We should be focusing right now on our domestic problems: the economy, socioeconomic reforms. There’s more than enough to deal with at home!” Others worried that their sons and grandsons could be sent to Ukraine to fight.

Despite the high level of support for both the “special operation” and the Russian regime overall, it is notable that there are now more dissenters in Russia today than there were in 2014. Eight years ago, no more than 10 percent spoke out against the annexation of Crimea (compared to 20 percent who disagree with the government actions in Ukraine in 2022). In 2014, only 11–12 percent of people said they were dissatisfied with Putin. Furthermore, in 2014, there were mass progovernment demonstrations organized by the government in support of its actions in Ukraine. Such gatherings were attended at their peak by tens of thousands of people, according to conservative estimates.17 But nothing of the sort is being staged today. So what has changed?

In recent months, there has been a significant decline in public support for participating in any type of protest, surely in response to a raft of restrictive measures imposed by the Russian government. Today, just 9–10 percent of respondents say they are prepared to attend a protest, less than half of the level only six months ago.18 Taking part in unsanctioned protests is now punishable by hefty fines and prison sentences for repeat offenses. Incitement of others to take part in unsanctioned protests and “the discrediting of the Russian Armed Forces” have also been criminalized.19 In addition, a nationwide ban on holding mass events introduced during the coronavirus pandemic has not yet been lifted.20 This restriction has been cited by officials for refusing to grant permission for anti-war rallies.21

Focus group participants said: “They have really clamped down on everything. There can be no more mass protests now.” “Protests are pointless, and people have realized that.” “There’s no point, they won’t achieve anything. Everyone wants to live well, and no one wants to take to the streets; they could go to jail or lose their job. People are scared.” And, “I went to a rally, and what happened? Did it change anything? Yes it did: I was fired!”

Yet even in these circumstances, despite such bans and threats of retaliation, some protests continue. According to human rights activists, 16,000 people were detained across 200 Russian cities for taking part in anti-war protests between the launch of the invasion on February 24 and the middle of July.22 While such numbers remain small in aggregate terms, they are testimony to the fact that parts of a minority segment of Russian society remains prepared to risk their well-being in order to express disagreement with their government.

The approval ratings of state institutions had already improved as of the end of last year amid mounting tensions along the Russian-Ukrainian border. But when hostilities broke out, support for the Russian authorities immediately shot up. That spike in March was reminiscent of the one seen after the annexation of Crimea back in 2014. In March 2014, government approval ratings rose from 69 percent to 80 percent. In March 2022, the increase was from 71 percent to 83 percent.23 This boost benefited all government institutions, including increased support for the ruling United Russia party.24 As in 2014, there was also a parallel spike in optimism over the state of affairs in Russia and the country’s future development.25 By the end of April, opinion polls were showing that more respondents felt “pride in their people.”26 The shock from the initial spike in inflation was beginning to wear off by the end of the spring, and people had already started adapting to the new situation.

These systematic surges of support in Russian public opinion demonstrate that overall, support for the regime and support for the “special operation” are largely the same thing. Nearly 90 percent of Putin supporters approve of the “special operation.” That figure is three times lower among Russians who are critical of Putin.

There are also differences between the current mood and that in 2014 (see figure 2). Today’s ratings surge is not accompanied by the euphoria that surrounded the Crimea annexation. In 2014, the dominant emotions among Russians were positive: pride in their country, a feeling that a historic injustice had been reversed, and joy over the prowess of the Russian military. Only 3 percent of respondents in 2014 mentioned feeling concerned or fearful.27 Today is clearly a time of mixed emotions. Even in March 2022, when the feeling of “pride in Russia” prevailed among respondents, especially among the group showing unconditional support for the “special operation,” about a third of Russians—including many supporters of the Russian campaign—were experiencing “anxiety and fear.” Still, those feelings of fear did not affect the level of support for the country’s leadership.28

Support for the authorities was as diverse as it was for the “special operation.” In March 2022, about 45 percent of people “definitely approved” of Putin’s actions as president: twice as many as in January. Almost as many (38 percent) “mostly approved” of him, with numerous reservations.29

For example, focus group respondents said, “Overall, I don’t agree with everything . . . My pension is small . . . but Putin’s policies are correct, because everywhere around us, there is intrigue against Russia” and “Right now we have to [approve]: you can’t oppose them when there is a war on!”

From their words, it can be concluded that international tensions, the growing pressure on Russia from Western countries, and the introduction of Western sanctions are encouraging the majority of the population to rally around the country’s leadership. This is precisely what happened back in 2014–2015.

People’s attitudes to what is happening in Ukraine depend on which sources they rely on for news and information. This factor carries more weight than the region where the respondent lives or even whether they have relatives in Ukraine.

There were many examples in the focus groups of respondents viewing events through a pro-Russian lens, despite having relatives or acquaintances on the other side of the border. Respondents described how “my work colleague’s mother is in Ukraine and sends her daughter something nearly every day about what [bad people] we are, that we are bombing their homes, and so on,” and “my niece lives in Kyiv; my brother did military service there, got married, and stayed there . . . I’m in favor of the launch of this operation.”

International tensions have had a significant impact on long-term trends involving popular trust in the accuracy of news information from different types of media outlets.30 In March 2022, there was a sharp increase (10 percentage points up from responses at the end of 2021) in people’s trust in television, which most Russians perceive as a source of “official information.” In recent years, viewership of and trust in television news had been decreasing steadily. There was also a simultaneous decrease (7–8 percentage points) in the level of trust in internet news sources, which had in recent years been growing steadily. Similar trends also occurred in 2014, when trust in official Russian media grew against the backdrop of the conflict.31