Link here.

Alexander Mercouris and Alex Christoforou discuss the Ukrainian counteroffensive in Kherson, September 2nd.

Oliver Boyd’s written summary is here.

By James Carden, Asia Times, 8/27/22

On August 23, it was reported that the US will be sending yet another multibillion-dollar aid package to Ukraine. This time it’s $3 billion in “security assistance” including six additional National Advanced Surface-to-Air Missile Systems (NASAMS); laser-guided rocket systems (Raytheon’s M982 Excalibur); 245,000 rounds of 155mm artillery ammunition; and 65,000 rounds of 120mm mortar ammunition.

That would bring total US lethal and non-lethal aid to Ukraine to $57 billion since the war began six months ago.

America’s seemingly unconditional support for Kiev’s maximalist war aims, which include the recapture and reincorporation of Crimea and the Donbas, leave one with the distinct impression that the West’s policy is evolving toward one of unconditional surrender on the part of Moscow – or, better yet from the perspective of Washington, regime change.

This seems especially true when one takes into account the US-led sanctions regime that has sought to collapse the ruble and crush the Russian economy. Indeed, the US and its NATO allies seem to be pushing the current proxy war between Russia and the West into a total one.

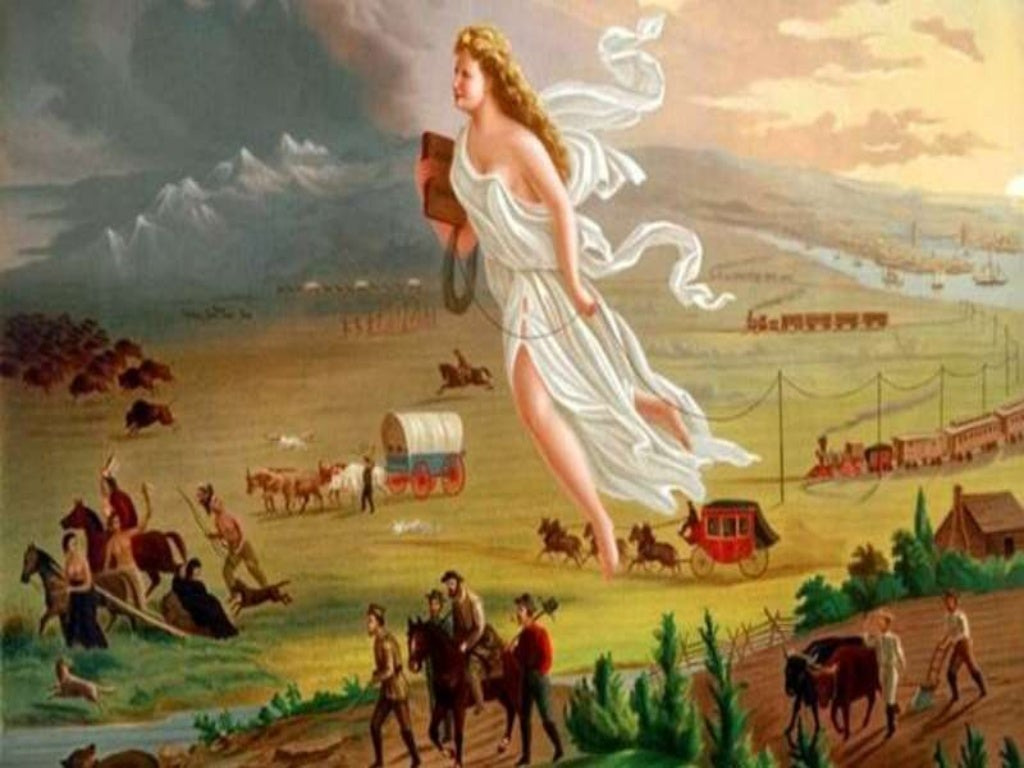

Kiev’s maximalist war aims have won easy US support in part because maximalism has long been a feature of American foreign policy.

Writing in the late 1990s, columnist William Pfaff noted that “the overall conception of American foreign policy in modern times ultimately derived from a Protestant conception of the United States as the secular agent of God’s redemptive action.”

Both Pfaff and the scholar-diplomat George F Kennan have criticized Woodrow Wilson’s maximalist conception of America’s involvement in the First World War. Pfaff described Wilson’s identification of the Great War as “the war to end war” as a “goal of such moral absolutism as to abolish the possibility of compromise.”

Kennan was of a similar cast of mind. Writing a half a century before Pfaff, in 1951, he noted that as World War I progressed, it “did not bring reasonableness, or humility, or the spirit of compromise to warring peoples. As hostilities ran their course, hatred congealed, one’s own propaganda came to be believed, moderate people were shouted down and brought into disrepute, and war aims hardened and became more extreme all around.”

Worryingly, the rhetoric of American leaders has become saturated with the language of maximalism. Recall that in March, President Joe Biden publicly called for a change of regime in Moscow, telling an audience in Poland, “For God’s sake, this man [Vladimir Putin] cannot remain in power.”

Biden and his national-security team have repeatedly warned the American people that, in the president’s words, “We need to steel ourselves for the long fight ahead.”

Biden’s undersecretary for policy at the Pentagon, Colin Kahl, said the new aid package was “aimed at getting Ukraine what they’re going to need in the medium to long term…. It is relevant to the ability of Ukraine to defend itself and deter further aggression a year from now, two years from now.” Note the expectation here is that the war will continue a year or two into the future.

Kiev’s maximalism is pushing the US, bit by bit, up the escalatory ladder. As Kennan noted, “A war fought in the name of high moral principle finds no early end short of some form of total domination.”

Though he did not live to see the hysteria that marks the current moment, Pfaff, who passed away in 2015, observed that Wilson’s legacy among the American foreign-policy elite was secure. And this troubled him.

“It is hard to explain,” he wrote, “why Wilson’s fundamentally sentimental, megalomaniacal, and unhistorical vision of world democracy organized on the American example and led by the United States should continue today to set the general course of American foreign policy under both Democrats and Republicans, and inspire enthusiasm for American global hegemony among policymakers and analysts.”

The unthinking maximalists of the US foreign-policy establishment discount the escalatory risks that Biden’s rhetoric and the billions of dollars in lethal aid carry in large part because of the messianism that has imbued the American foreign-policy tradition for much of the past century.

They play down, even outright dismiss, even the possibility of diplomacy with Moscow, all the while certain in the rightness of their crusade.

We’ve been here before.

James W Carden is a former adviser to the US-Russia Bilateral Presidential Commission at the US Department of State.

Link here.

By Prof. Walter Moss, History News Network, 8/28/22

Bolding for emphasis is mine. – Natylie

Who and what to believe about…. You furnish the ending. The question could be asked of almost any topic. The January 6 storming of the capitol building. The FBI seizure of boxes of documents from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago mansion. Global warming. The Inflation Reduction Act. As historians, one of our main tasks is to give students and other pursuers of history some guidance in terms of using various historical sources. How do we know which sources are more reliable than others? In our terribly polarized political world, it is terribly important to know which sources, and not just historical ones, are trustworthy. You don’t trust Fox News? Why not? What criteria are you using to make your judgment?

I have been led to these ruminations by reading about the ongoing Ukrainian war, mainly (but not exclusively) on Johnson’s Russia List (JRL), which daily contains the most diverse articles on that war (and can be emailed to you). The suffering caused by that conflict is immense. First, there are the Ukrainians, who are victimized by deaths, the destruction of all sorts of buildings including hospitals and schools, and displacements (often making them refugees). Then there are the world’s hungry, who cannot get sufficient food because of the disruption of exports of Ukrainian grain and other agricultural products. Western countries are expending large sums of money to help the Ukrainians, and their citizens will pay for this at the same time as they are hurting because of a reduction of Russian oil and gas exports and inflation, at least partly heightened by the war. Nor should Russian citizens be forgotten, and not only soldiers who are dying in Ukraine. Because of Western sanctions, a reduction of Western goods and services, and a strengthening of Putin’s powers (at least for now), the everyday life of some Russians has grown worse, but not nearly so bad as to threaten Putin’s regime.

But primarily whose fault is all this? Articles appearing daily on JRL (usually 20-25) and elsewhere offer differing opinions, including those blaming mainly Putin or Ukraine and/or NATO countries. In today’s Internet world–and that’s how I access JRL–too often people read and agree whatever material confirms their biases.

The first place to start then is to look inward and realize that we all have our biases. We may not think of them as such, but that may depend on how we define “bias.” In this essay, I’ll adhere closely to the viewpoint of the website AllSides, which suggests that it is a “particular tendency, trend, inclination, feeling, or opinion” that affects our judgment. Further, the site adds, “Some sort of standpoint or bias is an inherent and innate feature of the human mind—something that literally cannot be ‘escaped’ or ‘shelved.’ Preferences, inclinations, and partialities help us to filter information, order our psyches and navigate the world.”

That may be true, but rather than just read or hear material that confirms our biases, we should prioritize truth-seeking. This is especially true for historians. As I wrote previously on this site, “‘Tell the truth’ should be as central to our mission, as ‘First, do no harm’ is to doctors and nurses.”

Okay then, but how can we counter our biases and move closer to truth? Primarily, we should try to balance them off by looking at contrary views. If we are inclined to a liberal viewpoint consider a conservative one. If we tend to be anti-Russian, then look at some pro-Russian sources. And, of course, vice versa. In one of President Obama’s best, and still very relevant, speeches, he told University of Michigan graduates in 2010, “If you’re somebody who only reads the editorial page of The New York Times, try glancing at the page of The Wall Street Journal once in a while…. It may make your blood boil; your mind may not be changed. But the practice of listening to opposing views is essential for effective citizenship.”

Looking at opposing views and trying to really understand them is also necessary for “strategic empathy,” which is “the skill of stepping out of our own heads and into the minds of others. It is what allows us to pinpoint what truly drives and constrains the other side.” Achieving such empathy is important for historians, but also extremely helpful in attempting to transition from war to peace.

Although the above may be good general advice, the question still remains: how do we specifically apply it to the present war in Ukraine? To answer that let’s start with examining the JRL contents (roughly some 250 selections) from mid-August (10th-20th).

The diversity is indeed impressive. Articles from major Western media sources like The New York Times and The Washington Post, which are generally critical of “Putin’s war,” oppose the viewpoint of JRL’s repostings from Russian government-controlled sources such as TASS and RT. There are also many other repostings of Western and Russian views that vary widely. Although not just parroting Putin’s justification for the invasion, almost all of the opinions coming from Russian groups or individuals–like Russia in Global Affairs, the Valdai Discussion Club, and The Russian International Affairs Council–are more critical of Ukrainian/Western policies than of those of Russia. Western sources tend to be more varied. While some generally favor Ukrainian/Western responses to the Russian invasion, others are more varied, with some being quite critical.

Western sources include some U.S. media from both the left and right, as well as many British papers and magazines (e.g., The Economist, Guardian, Financial Times, The Spectator), plus media organizations like Reuters News Agency and the BBC. Occasionally, an article from other NATO countries, such as from Germany’s Der Spiegel or Latvia’s Meduza (a Russian- and English-language independent Russian news website), will also appear on JRL.

Less frequently materials come from neither Russia nor the West. There are some, but not many, from Ukraine itself, for example the Kyiv Post, and a few from India and the Middle Eastern site Al Jazeera.

Still other selections come from websites that are more difficult to classify. For example, there is that of Moon of Alabama, which once declared, “The New York Times continues its shameless pro-Ukrainian propaganda campaign that is deceiving its readers.” Then there is that of Awful Avalanche, a blog by a self-proclaimed Russian Marxist. Occasionally, even one of my own pieces on Russia or Ukraine, first posted on HNN or the LA Progressive, will also be reposted on JRL.

In addition to the various sources that Johnson reposts, we are daily bombarded by other media news and opinions regarding Ukraine. Earlier I mentioned the Website AllSides. It provides bias evaluations on over 14,000 sources. Media Bias / Fact Check also evaluates media sites, as does Biasly. Thus, readers can gain some insight into many, but not all, of the biases of the media sources they access.

In addition to knowing the general biases of most sources and how to spot such slants, there are several specific approaches we can take to news regarding the Russian-Ukrainian war. First, be wary of any source that presents an overly simplistic view of the conflict. In previous HNN essays (see, e.g., here and here) I have written of “Putin’s fear and distrust of NATO expansion in eastern Europe” and mentioned the opinion of some experts that “talk of bringing Ukraine into NATO has been . . . irresponsible.” But, more recently, I have also indicated that “none of that justifies the Russian invasion of Ukraine and the innumerable tragedies that it has caused.” Thus, no justification, but the West have given Putin reason to be suspicious regarding NATO expansion.

Second, ask yourself how any proposed policies or actions are going to help end the invasion of Ukrainian territory. About two months ago Gerard Toal wrote an article entitled “The West must help Ukraine to end this terrible war.” Five years ago, I reviewed his Near Abroad: Putin, the West, and the Contest over Ukraine and the Caucasus. I considered it an excellent introduction to its subject. In his more recent article, he pleads for Western supporters of Ukraine to take a realistic view of the conflict:

“Not wanting to hear unwelcome realities is also an affliction of some international supporters of Ukraine. Everyone wants Ukraine to win. Few specify in detail what that really means, and how many Ukrainians they are willing to sacrifice for their idea of victory. Casting the Ukrainian struggle in heroic terms, they have favoured what is desirable over what is probable, what is ideal over what is realistic. With so many losing their lives, that is reprehensible.”

Third, be especially realistic about what actions Putin is likely to take. Angela Stent, author of Putin’s World: Russia Against the West and with the Rest (2019), has stated that “he is not going to give up on his goal of subordinating Ukraine…. This is something that’s driven him for years, something he’s obsessed with.” On the other hand, another expert on Putin, Fiona Hill, pointed out several months ago that “we don’t know how much longer this is going to go on, but we should . . . get this resolved as soon as possible,” both through diplomatic and military means. Regarding the latter, she adds that “the more that the Russian military action can be blunted,” the greater likelihood that Putin might be willing to accept some sort of diplomatic solution. A previous book on Putin, which she co-authored, stated that “Putin is a pragmatist, not an ideologue.” And despite his possessing strong and sometimes skewed views on Ukraine and the West, that still seems to be true.

We may not be able to predict exactly what Putin will do in various possible future scenarios, but considering any likely responses from him can also not be ignored.

Walter G. Moss is a professor emeritus of history at Eastern Michigan University, a Contributing Editor of HNN, and author of A History of Russia. 2 vols.

By Scott Ritter, Consortium News, 9/1/22

Six months into Russia’s “Special Military Operation,” fact-challenged reporting that constitutes Western media’s approach to covering the conflict in Ukraine has become apparent to any discerning audience. Less understood is why anyone would sacrifice their integrity to participate in such a travesty. The story of William Arkin is a case in point.

On March 30 (a little more than a month into the war), Arkin penned an article which began with the following sentence: “Russia’s armed forces are reaching a state of exhaustion, stalemated on the battlefield and unable to make additional gains, while Ukraine is slowly pushing them back, continuing to inflict destruction on the invaders.”

Arkin went on to quote a “high-level officer of the Defense Intelligence Agency,” who spoke on condition of anonymity, who declared that “The war in Ukraine is over.”

A little less than three months later, on June 14, Arkin wrote a piece for Newsweek with the headline: “Russia Is Losing the Ukraine War. Don’t Be Fooled by What Happened in Severodonetsk.”

Apparently neither Arkin nor his editorial bosses at Newsweek felt any need to explain how Russia could be losing the war twice.

Anyone who has been following what I’ve been writing and saying since the beginning of Russia’s “Special Military Operation” in Ukraine knows I hold the exact opposite view. Russia, I maintain, is winning the Ukraine conflict, in decisive fashion.

But I don’t write for Newsweek.

William Arkin does.

Arkin proclaims that Russia is losing though it had, at the time the article was published, just taken the strategic city of Severdonetsk, killing and capturing thousands of Ukrainian forces, and rendering thousands more combat ineffective since they had to abandon their equipment to flee for their lives. (Russia has since captured all of the territory encompassing the Lugansk People’s Republic, including the city of Lysychansk, inflicting thousands of additional casualties on the Ukrainian military.)

“The Russian army’s so-called victory,” Arkin proclaimed at the time, “is the latest installment in its humiliating military display and comes with a crushing human cost.”

The humiliating display instead is Arkin’s lack of acumen in conducting an independent assessment of the military situation on the ground in Ukraine.

This was again reinforced last week when Arkin penned another article in which he helps disseminate the outlandish claims of his Pentagon sources.

“[F]rom late February through August, with only a moderate infusion of weapons from the West, some supportive declarations from Western leaders and a smattering of ‘We Stand with Ukraine’ signs on U.S. lawns,” Arkin writes, Ukraine has been able to “hold at bay the mighty Russian military,” something apparently none thought it could do.

Ignore the jaw-dropping contention by Arkin that the tens of billions of dollars in military assistance provided by the U.S. and its NATO and European allies constitutes but “a moderate infusion of weapons.” No, don’t ignore it — focus on it. This is the signature style of Arkin and his Pentagon handlers, a sort of Orwellian double-speak where one can rest assured whatever bold statement is made, the truth is the exact opposite.

Arkin quotes “U.S. intelligence officials who have been watching the war,” writing that “Russian troops have had to contend with bad battlefield leaders, inferior weapons and an unworkable supply chain.”

Anyone who has been tracking the events in Ukraine might have thought that this was the situation as it applies to the Ukrainian military. Not so, says Arkin and his source. Moreover, it is not Ukraine’s President Volodymyr Zelensky who has been interfering with his Ministry of Defense, but Russian President Vladimir Putin with his. These same Russian troops, Arkin declares, have “also been hobbled by Putin himself,” who has “ignored, overruled and fired his own generals.”

This is baseless fiction, written by a man who seems determined to cement himself in the annals of the Russian-Ukraine conflict as an unabashed Ukraine partisan and vehicle for Pentagon information warriors. Arkin’s narrative of the war to date is so far removed from the factual record it belongs in The Onion.

What Arkin writes cannot even be called propaganda, because for propaganda to be effective it needs to be both believable at the moment of consumption, and able to sustain a narrative over time. Arkin’s work fulfills neither criterion.

His Sources

Like most erstwhile journalists covering the conflict for western media outlets, Arkin appears to be a prisoner to his sources, which in this case are a combination of anonymous U.S. defense intelligence personnel and pro-Ukrainian propagandists.

I used the term “erstwhile” in describing Western journalists because normal journalistic standards dictate that one seeks to report a story — any story — from a position of dispassionate neutrality, drawing on sources which reflect all sides of the story.

There is nothing wrong about drawing conclusions from such reporting, even assigning weight when it comes to which aspects of the coverage are deemed more credible than others. But before such conclusions can be made, foundational reporting needs to take place. Simply parroting what you’re being told from sources exclusively drawn from one part of the story is stenography.

In the interests of full disclosure, Arkin and I were colleagues for a brief period in late 1998-early 1999, when we were both contracted to NBC News as “on air talent” to talk about the situation in Iraq. Arkin apparently did not hold my analysis in high regard then. I have no idea what he thinks today — Consortium News has reached out for an answer, but as of publication has not received a reply.

Arkin did not respond to an invitation to debate me on Ukraine on a weekly podcast I do with Jeff Norman.

I’ll let our respective track records speak for themselves, especially when it comes to Iraq and the threat posed by weapons of mass destruction. Arkin says he is “proud to say that I also was one of the few to report that there weren’t any WMD in Iraq and remember fondly presenting that conclusion to an incredulous NBC editorial board.”

I’m pretty sure I was saying something similar to an equally incredulous Congress and to the entire mainstream U.S. media (NBC included), as well as the international press corps.

Congratulations, Bill — we once were on the same page.

But no more.

Arkin’s Achievements

Arkin is no run-of-the mill journalist. He’s a smart guy. He got accepted to New York University, although he dropped out to join the Army, claiming NYU “wasn’t for me.” While stationed in Berlin, he completed his undergraduate studies, getting a bachelor’s degree in government and politics. After leaving the Army he got a master’s degree in National Security Studies from Georgetown University.

For the next 40 years, Arkin worked for numerous employers, specializing in nuclear issues and military affairs, before landing his current gig as Newsweeks‘ senior editor for intelligence.

For The Washington Post in 2010, after a two-year investigation, he wrote a ground-breaking story with Dana Priest about the vast and until then little-understood explosive growth of the national security state post 9/11.

Arkin then showed integrity when he resigned from MSNBC and NBC News in 2019. His reasons for leaving, spelled out here, include how he was “especially disheartened to watch NBC and much of the rest of the news media somehow become a defender of Washington and the system.”

In March this year he wrote a startling story that questioned the dominant Western reporting that Russia was committing repeated war crimes by wantonly slaughtering huge numbers of civilians just for the hell of it. [https://www.newsweek.com/putins-bombers-could-devastate-ukraine-hes-holding-back-heres-why-1690494]

“As destructive as the Ukraine war is, Russia is causing less damage and killing fewer civilians than it could, U.S. intelligence experts say. Russia’s conduct in the brutal war tells a different story than the widely accepted view that Vladimir Putin is intent on demolishing Ukraine and inflicting maximum civilian damage,” he wrote.

The article corroborated what Russia had been saying all along, which until that point was dismissed in the West as propaganda.

So how does Arkin transition from debunking Ukrainian and Western propaganda about Moscow deliberately killing huge numbers of civilians, to embracing the fanciful notion that Russia is losing the war? (Further underscoring Arkin’s assessment of Russia’s battlefield performance is the uninterrupted string of battlefield successes by Russia in the Donbass since that June article was published, further undermining his argument.)

It’s not a lack of education that has led Arkin down the path so many of his colleagues in mainstream media have stumbled down; there is no doubting the man is not only well educated, but also innately intelligent, something that doesn’t necessarily follow the other.

Military ‘Expertise’

Arkin can be said to be a victim of his own CV, which is light on relevant military experience for someone selling himself as an expert in military affairs based on his time in the U.S. Army.

Arkin purports to be one of the foremost military analysts of our times, a man whose track record in military affairs dates to his time as a junior enlisted soldier in the U.S. Army where, from 1974 to 1978, he served in occupied West Berlin as an intelligence analyst working for the Deputy Chief of Staff Intelligence (DCSI), U.S. Commander Berlin (USCOB).

On his WordPress page, Arkin writes that in the army he “rose to be senior intelligence analyst for the Berlin military occupation authorities and served under civilian cover as part of a number of clandestine human and technical intelligence collection efforts.”

In Berlin, Arkin adds in his LinkIn bio, “I worked on a number of clandestine projects and was an analyst of Soviet and East German activities in East Germany.”

He was not just any military analyst, mind you, but someone who, according to himself, “was once one of the world’s leading experts on two military forces that don’t even exist anymore.” I worked closely with military officers who were in fact the foremost experts on both the Soviet and East German militaries during the time Arkin served. This Newsweek senior editor has engaged in more than a little self-promotion.

That someone of the rank of specialist or sergeant (I have no idea what rank Arkin achieved, but four years’ time in service is a self-limiting reality when it comes to advancement) being the “senior intelligence analyst” in all of Berlin on matters pertaining to the Soviet military is patently absurd; Berlin was home to numerous specialized intelligence units and organizations, any one of which would have been staffed with personnel far more senior and, as such, experienced, in intelligence analysis on the Soviet and East German target than Arkin. Simply put, Arkin was not, nor has he ever been, one of the world’s leading experts on the Soviet military.

Not even close.

Arkin was never involved in combat arms, nor did he serve in combat. Without that experience he cannot understand the military realities of war — logistics, communications, maneuvering, fire support, etc. Berlin was, from everything I’ve heard, a fascinating place to serve — but it wasn’t combat.

Not even close.

As Arkin has no combat experience, his military analysis is held hostage to his sources within the Defense Intelligence Agency who pass along such cutting-edge insights as the notion that Russia is suffering ten casualties for every Ukrainian soldier lost since the Donbass offensive began in April.

Arkin seemed unaware of documents alleged to have been leaked from the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense, dated April 21, which state that Ukraine had, as of the date, suffered 191,000 combined killed and wounded. According to Arkin’s math, this would mean Russia has suffered nearly 2 million casualties of its own.

Despite the absurdity, Arkin keeps parroting what his Defense Intelligence Agency sources tell him.

He repeats, without hesitation, his intelligence source’s assessment of Ukraine’s “greater morale and motivation, better training and leadership, superior knowledge and use of the terrain, better maintained and more reliable equipment, and even greater accuracy.”

It doesn’t matter that literally every assertion made by Arkin’s intelligence source is demonstrably false. If Arkin knew about artillery (the ongoing conflict between Russia and Ukraine is primarily an extended artillery duel), he would understand the concepts of probability of hit and probability of kill, and how the volume of artillery fired increases both.

He might then understand how absurd it is to think that an artillery duel where one side fires 6,000 rounds and the other 60,000 rounds could produce an outcome where the side firing 10 times fewer rounds achieves a 10-fold advantage in lethality.

Any expert on Soviet/Russian military affairs would have known that artillery was going to be a major factor in any large-scale combat operation involving Russian forces. By way of example, three days before the Russian operation began, I tweeted (when I could still tweet):

“If you haven’t done a schedule of fires for at least three artillery battalions in the field using live rounds while maneuvering, I’m probably not interested in your military opinion about Ukraine.”

Arkin, to the best of my knowledge, has never done a schedule of fires for multiple battalions of artillery. His apparent lack of knowledge of artillery shows when he repeats verbatim the dreck fed him by his intelligence sources.

Arkin’s has to be aware that NBC News reported about the deliberate declassification and release by the U.S. intelligence community of intelligence information that intelligence officials knew was not true. And yet, Arkin still relies on these types of sources to provide the fodder for his headline-grabbing tales. The question of Arkin’s motives in writing such stories now remains.

That someone with Arkin’s background would allow a lifetime of diligent work to be squandered by serving as little more than a shill for U.S. intelligence is one thing. That media outlets like Newsweek keep printing it is another. Together, these twin phenomena represent what I call “The Arkin Effect,” which is nothing less than the total debasement of journalism in the U.S. when it comes to Russia’s war in Ukraine.

Six months into Russia’s “Special Military Operation”, most military analysts admit that Russia enjoys the upper hand on the battlefield, despite the billions of dollars in military aid that has been sent to Ukraine by the U.S. and its European allies.

But not Bill Arkin and his employers at Newsweek. They seem to be content with serving as the Defense Intelligence Agency’s stenographers, putting out stories which have not, and will not, stand the test of time.