By Oliver Boyd-Barrett, Substack, 12/1/24

The Economy

Russia’s new military budget for 2025-2027 commits 13.5 trillion rubles (32.5 of the total budget; equivalent to $145 billion) per year to the war.

This will doubtless run the risk of overheating the economy, especially given manpower shortages for the defense industries, and adding further pressure on interest rates that now exceed 21%, and on inflation which is around 8%. This is in the context of a troubling fall in the international value of the ruble (7% depreciation in the past seven days, now on a par with its value in the opening phase of the SMO in 2022), in part connected to a fall in the price of Russian oil and gas. This is likely the result of a recent US imposition of sanctions on Gazprom Bank. That the US delayed so long targeting the Gazprom Bank is indicative of the importance to the West of continuing Russian trade in oil and gas. But at this time, it would appear, the US needs more than anything else to inflict pain on Russia, regardless of the accompanying pain to the West.

All this, it should be emphasized, is occurring in a context of (1) a healthy GNP that until the Central Bank’s recent measures to apply the brakes, was increasing at an annual rate of almost 4%; (2) generously increasing wages and benefits to military personnel and their families; (3) a doubling over the past year in the rate of increase of the real value of household wealth; (4) a reinvestment into the Russian economy of flows of money that had previously been exported and of the profits of former Western corporations that were formerly siphoned off to the West; (5) rapidly expanding markets for Russian energy and other goods in China, India and other countries of the Global South.

Further, none of the problems outlined above should be regarded as insuperable. Many are natural to the ebb and flow of all economic cycles. Russian industry and agriculture overall are very strong. Many if not most of the weaknesses that resulted from Western sanctions and the departure of Western corporations have been overcome in whole or in part, as just mentioned, by the enhancement of Russian trade with China and India and other countries of the Global South and by sophisticated work-arounds to avoid Western sanctions.

Further still, the West is divided by an economically crippled Europe, ever more impoverished by the transfer of its wealth in weapons, money and, soon, human lives, to Ukraine, and ever more economically dependent on the US for markets and supplies and for its fanatical continuation of the war. The US grows stronger as a result of this imbalance but not so much that the upward trajectory of its approximately $35.5 trillion debt load is significantly off-set any time in the forseeable future, helping to explain why, somewhat pathetically, Trump now threatens the BRICS (representing the Global South or, better still, the Global Majority) with sanctions if they try to topple the dollar as hegemonic currency.

Extending but Not Breaking Russia

Russia’s increased military budget will be sufficient, in conditions in which it has proven superiority over the West in both nuclear and non-nuclear (but nuclear-comparable, as in the case of the Oreshnik) weapons, to (1) continue its advances on Ukrainian territory (even as Ukraine prepares a new offensive in Zapporizhzhia, and possibly on Belgorod and Bryansk); (2) head off Western attempts to stage a “Maidan” style coup d’etat (or the “Ukrainization of a Causcasian State”) against the recently elected government of pro-Russian prime minister Irakli Kobakhidze in Georgia, where street protests in Tbilisi constitute the latest Western-financed splurge of “pro-democratic” violence and coercion); (3) halt the progress of a Turkish-Israeli-Western backed jihadist offensive from Idlib on Aleppo and Hama in Syria; (4) head off anticipated Western provocations against the government of Belarus in Minsk during the lead-up to presidential elections that are scheduled for 26 January 2025; and (5) counter Ukrainian designs on pro-Russian Transnistria in an attempt to seize its Russian military assets and to support Moldavan aspirations to EU and NATO membership.

Fog Lifts in Syria

The situation in Syria as of the afternoon of December 1st, California time, offers greater clarity as to purpose as well as stabilization of the jihadi threat. The overall purpose and the reason why this offensive shows signs of careful, secret planning and organization, is that Western and Israeli sponsors of violent jihadism see in Syria a strategic weapon with which to hold down Russia and Iran.

Turkiye’s principal interest, however, is somewhat different. I would suggest that it is to use jihadi forces for which it has long been responsible for containing in the northwest of Syria (centered in Idlib province, whose goverance has now been taken over by the former Qaeda affiliated HTS in conjunction with the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army [SNA]) to (1) force a reluctant Syrian President Assad into settling the conflict between Turkey and Syria in such a way that both parties can undermine the establishment of a US-protected Kurdish enclave; (2) update and preserve on a more permanent basis the buffer zone along Turkey’s long border with Syria; and (3) re-settle Syrian refugees in southern Turkiye back to Syria.

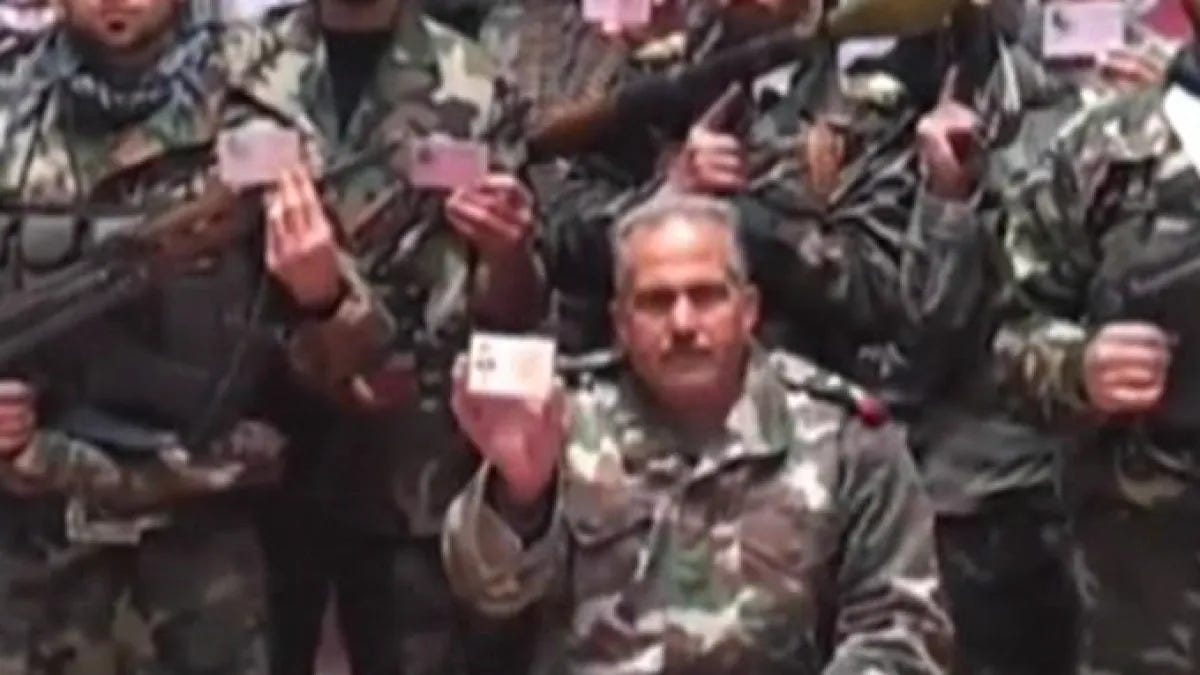

The overall size of the SNA-HTS army has been estimated at 15,000. Modest. Yet it was strong enough to take the Syrian army completely by surprise in and around Aleppo, the second largest Syrian city and its most important industrial base. This represents a very major, an unspeakable, fiasco for the Syrian army and for the Damascus government.

Fortunately, it does not, however, represent a collapse of the Syrian army as was at first feared. With the help of Russian aerial bombing, the supply of Russian drones, and the deployment, it is reported, of up to 5,000 Russian Wagner soldiers, the Syrian army forces appear to have halted the SNA-HTS advance in Hama. Earlier reports suggest that an uprising in Daraa has been suppressed and that an attempted coup d’etat in Damascus has come to nothing. The whereabouts of Assad are something of a mystery and some reports have suggested that he is in Russia. There were consultations with Moscow and Assad before the most recent events.

Russian Interests

Russia, therefore, has clearly demonstrated its determination to support Damascus. It has many incentives to do so (1) it has naval, air force and army facilities in Syria; (2) it is a very long-standing ally of Syria; (3) it needs good relations with Syria in order to prepare for a likely upcoming regional, conceivably even a world war, starting with a conflagration between Russian ally Iran, and Israel, a conflict that Israel seems to lust for even as pro-Western elements in Tehran pathetically cling to fantasies about a sanctions-busting deal with Trump.

At home, the Kremlin faces considerable skeptcism among civilians as to the benefits of yet another foreign military adventure. In short, I would conclude that Russian support for Syria is dependable; its support for Assad – and not for the first time – hangs in the balance.

While Turkiye is assumed by most commentators to have played a major part in the invasion, this has not prevented Moscow from proposing a resuscitation of the Astana accord of 2017 whereby Russia, Turkiye and Iran consult together on policy with respect to Syria. Given that Russia is not, therefore, breaking off relations with Turkiye, – no matter how mecurial, even treacherous and unpredictable is the behavior of Erdogan – suggests that it is interpreting Erdogan’s motivation along the lines suggested above namely, that he wants to resolve the conflict between Turkiye and Syria, and to clean up the mess for which Ergodan himself carries major responsibility from the time when he broke off relations with his quondam friend, Assad, in 2011, and committed Turkiye to a regime-change war fought alongside the CIA, using arms released from NATO’s murder of Ghadaffi in Libya, and assuaged with protected jihadi R&R centers in Diyabakur.

Erdogan’s allies included the Arab theorocracies of Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Jordan, UAE and the Muslim Brotherhood, amidst the skilful meddling of Britain, the Netherlands and France through chemical weapons hoaxes, sinister false flags perpetrated by the White Helmets, and a multitude of other innovative misinformation and disinformation strategies.

Ankara, by the way, denies responsibility. But more plausible reports speak of a war-room in Turkey that have brought together Western military and Turkish operatives.

Assad, his failure to negotiate with Erdogan notwithstanding, has been successful in repairing relations with many of his former adversaries (including Saudi Arabia, the UAE and the Arab League as a whole), some of whom are joining Syria’s friends such as Iraq, Iran and even the Lebanese-based Hezbollah in rushing support to Syrian troops.

SNA and HTS remain in control of Aleppo; the SNA have control over the Kuweices base, and HTS controls the airport. The Syrian army and the Kurdish SDF are defending the Tell Rifaat district. But there will almost certainly be a Syrian Army counter-offensive in the next few days.

None of this takes away the grave indications of something seriously wrong in Damascus. Of course, the major reasons that have allowed such a lightening invasion by the rebel Sunni forces of Idlib on Aleppo, include (1) the deep impoverishment of the Syrian economy, and (2) of 90% or more of the Syrian people as a result (3) of a Western-instigated jihadist “civil war” from 2011, involving (4) the usual Western incitement of extremist Sunni, Muslim Brotherhood-style ideological violence, building (5) upon the first Muslim Brotherhood uprising against Bashar Assad’s father in 1980, and (6) not forgetting the US-Kurdish purloining of Syrian oil and agricultural wealth in the northeast over the past five to ten years, nor (7) the cruelty and cynicism of the US Caesar Act sanctions that have prevented the most basic of post-conflict rebuilding.

The Syrian army during the civil war survived in large measure by its ability to decentralize and to localize but at the expense of a certain tendency to warlordism that others might simply label corruption. This too would surely have been a factor.

But such a monumental failure of intelligence and, consequently, such a horrendous failure of preparation as has been demonstrated over the past few days must also be attributed to Damascus and to Assad who has had, since his coming to power well over twenty years ago, a reputation for the appearance of progressive intent coupled with an inability or unwillingness to follow through.

The Turkish-controlled northwest of Syria extends as far west as Yayladagi, next to Turkey’s Hatay province deep inside Syria, to Oabasin in the east and from Rajo and Elbeyli in the north to Kafr Uweid in the south. The recent invasion by SNA and HTS forces has reached through Aleppo as far south as As-Smeiriye, Ras-al-Ain and Saraqib.

Russian Advances in Ukraine

In Ukraine, Russia’s current advances are freshest:

(1) In the Vremivka/Velyka Novosilka area in Donetsk, where Russian forces have moved westwards from Novodonetske and north from Staromaiorske and Urozhaine, up through Makarivka in the direction of Storozheve, Vremivka, and Velyka Novosilka. Only one supply road now connects Velyka Novosilka to Ukrainian sources in Uspenivka to the west, a road that is vulnerable to being cut off by Russian forces moving north from Rivnopil to Novosilka;

(2) To the southeast of the Ukrainian stronghold of Uspenivka, Russian forces have established control over Illynka, and are advancing towards the adjacent settlements of Velyzavetivka and Romanivka in the direction of Vesely Hai;

(3) Around the Kurakhove reservoir, Russian forces now control some 50% of the town of Kurakhove on the southern bank, and are advancing in the direction of Dachne to the west while, north of the reservoir, Russian forces control Berestky and much of the territory to its north, and Stan Terny at the western end;

(4) Russian maneuvers are forcing the flight of Ukrainian forces westwards towards Shevchneko, very close to the major city of Pokrovsk. West of Sedove, Russian forces have taken or are moving on Pushkine, Petrivka, Zhovte, Novotroitske and Novopustaynka. They will aim to divide the city of Pokrovsk itself from adjoining Myronhohad. Elsewhere,

(5) Russian forces continue to bomb settlements north of Russian-held Mykoaivka towards Siversk, or westwards from Vyimka; establish footholds west of Oskil river in northern Kupyansk with a view to outflanking the city of Kupyansk from behind and, possibly, moving north to bring reinforcements to the city of Vovchansk, whose northern territory Russia now controls. Meanwhile the area controlled by Ukrainian forces on the Russian territory of Kursk continues to contract, its area of control (north of Ukrainian-held Suzhda), centers on Kryglenkoye, between Novoivanovka to the west and Malaya Loknye to the east.