By Kevin Gosztola, The Dissenter, 4/26/25

The following article was made possible by paid subscribers of The Dissenter. Become a subscriber with this discount offer and support journalism that stands up to attacks on freedom of the press.

United States Attorney General Pam Bondi ended a Justice Department (DOJ) policy that explicitly discouraged federal prosecutors from forcing journalists to reveal their sources and other sensitive information, including information obtained from potential leaks.

With new guidelines, members of the news media who refuse to cooperate with prosecutors could be arrested for contempt. If accused of contempt, they could be fined or jailed.

The move by Bondi comes as Director of National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard has “referred” three alleged “intelligence leakers” to the DOJ for criminal prosecution.

According to Gabbard, one of those individuals allegedly leaked to the Washington Post. The policy change effectively gives the green light to prosecutors to subpoena Post reporters and other staff.

DONATE: Support The Dissenter’s Independent Journalism

In October 2022, Attorney General Merrick Garland adopted changes to “news media guidelines” that were celebrated by journalist associations and press freedom groups. As the Reporters Committee for Freedom of the Press (RCFP) described, for the first time, guidelines prohibited prosecutors “from using subpoenas or other investigative tools against journalists who possess and publish classified information obtained in newsgathering, with only narrow exceptions.”

On April 25, 2025, Bondi issued a memo [PDF] that voided those changes. The memo informs all DOJ employees that members of the news media “must answer subpoenas,” and it also applied to court orders and search warrants intended to “compel the production of information and testimony.” Bondi will approve all “efforts to question or arrest members of the news media.”

The memo further suggests that Bondi will only approve subpoenas, court orders, or search warrants when the information sought is “essential to a successful prosecution” and prosecutors have “made all reasonable attempts to obtain the information from alternative sources.” Yet the DOJ has wide discretion to conduct investigations however it chooses, and the guidelines hardly mean that Bondi and the DOJ will not trample over the rights of journalists.

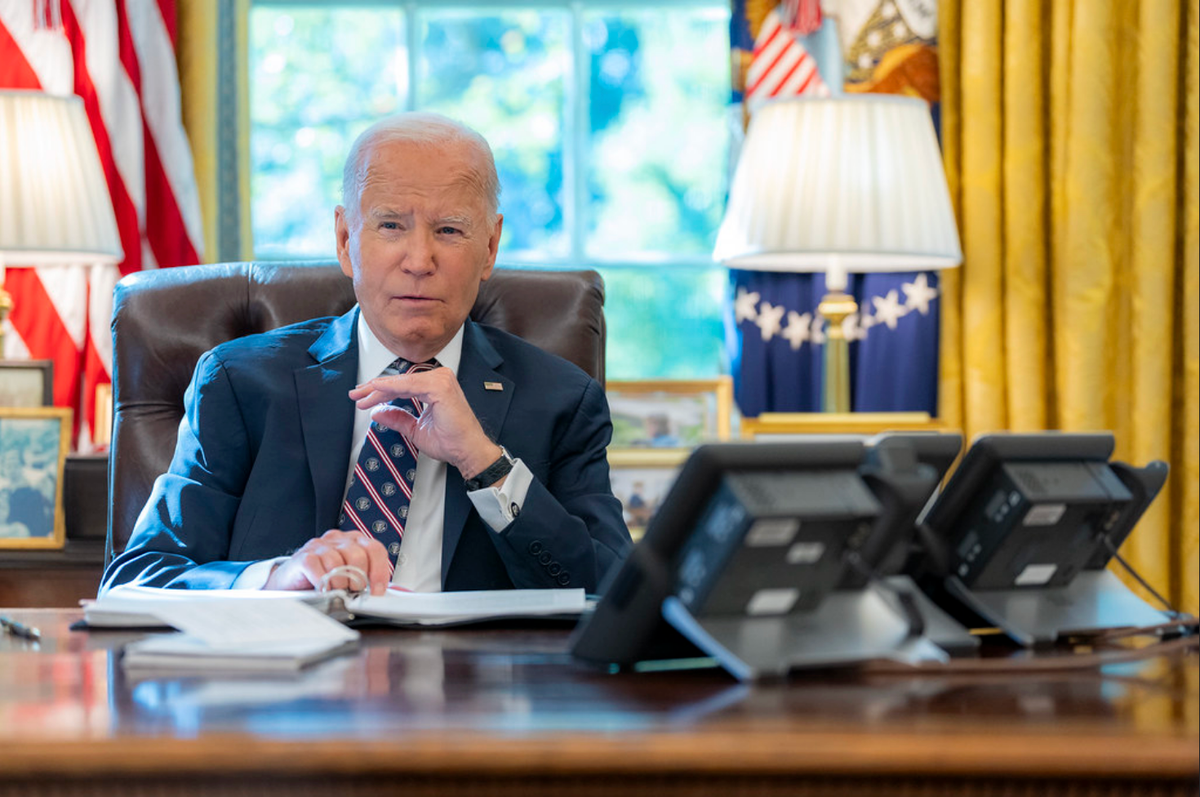

Bondi cast this development as a necessary part of winning an information war against President Donald Trump’s political opponents within and outside of the government. Specifically, she accused President Joe Biden’s administration of abusing “Garland’s overly broad procedural protections for media allies by engaging in selective leaks in support of failed lawfare campaigns.”

“The leaks have not abated since President Trump’s second inauguration, including leaks of classified information,” Bondi added. “This Justice Department will not tolerate unauthorized disclosures that undermine President Trump’s policies, victimize government agencies, and cause harm to the American people.”

Subscribe To The Free Edition Of The Dissenter

Quoting a stunning executive order from Trump that singled out a former official as an “egregious leaker,” Bondi echoed the assertion that disclosures of information related to foreign policy, national security, or “government effectiveness” could be characterized as “treasonous and as possibly violating the Espionage Act.”

Bondi stated, “The perpetrators of these leaks aid our foreign adversaries by spilling sensitive and sometimes classified information on to the Internet. The damage is significant and irreversible. Accountability, including criminal prosecutions, is necessary to set a new course.”

Garland’s protections for reporters stemmed from a backlash to news reports, which revealed that Trump’s first administration had secretly subpoenaed the communications records of reporters at the Post, CNN, and the New York Times.

In fact, after Biden assumed office in 2021, the DOJ did not immediately stop Trump’s retaliation against the press. DOJ officials even imposed an “unprecedented” gag order against Times executives.

DOJ officials eventually met with media representatives to tamp down outrage and agreed to limits on national security leak investigations. The overture was similar to Attorney General Eric Holder’s response to widespread media disapproval in 2013, when it became known that President Barack Obama’s administration had seized records from “more than 20 separate telephone lines assigned to [the Associated Press] and its journalists.”

Throughout the Biden administration, a coalition of groups recognized that the protections for press were subject to change under future administrations. They urged the U.S. House of Representatives and U.S. Senate to codify the changes into law by passing the PRESS Act, which would have established a federal reporter’s shield law.

The House passed the PRESS Act in January 2024, however, despite bipartisan support, the shield law languished in the Senate for months as Democrats did nothing to move the bill for a vote.

In April 2024, when White House press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre was asked if Biden supported the PRESS Act, she uttered a platitude: “[J]ournalism is not a crime. We’ve been very clear about that.” But the White House refused to back legislation that would protect reporters from the type of attacks on their newsgathering that Bondi just authorized.

After Vice President Kamala Harris lost the presidential election to Trump, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer and other Democrats, like Senate Judiciary Committee Chair Dick Durbin, suddenly recognized the need to pass the PRESS Act. It was too late. Trump came out against the shield law, instructing Republicans to “kill” the bill. Republican Senator Tom Cotton obeyed Trump and blocked the bill, as he had done during a previous session of Congress.

“Every Democrat who put the PRESS Act on the back burner when they had the opportunity to pass a bipartisan bill codifying journalist-source confidentiality should be ashamed,” Freedom of the Press Foundation advocacy director Seth Stern said, after Bondi revoked press protections. “Everyone predicted this would happen in a second Trump administration, yet politicians in a position to prevent it prioritized empty rhetoric over putting up a meaningful fight.”

“Because of them, a president who threatens journalists with prison rape for protecting their sources and says reporting critically on his administration should be illegal can and almost certainly will abuse the legal system to investigate and prosecute his critics and the journalists they talk to,” Stern added.

Trump’s second term already presents more danger to freedom of the press than his first term, particularly because there is nothing constraining his administration. They are hellbent on weaponizing government and engaging in the kind of lawfare that they fervently believe the Biden administration waged against them.

As The Dissenter thoroughly recounted when Biden’s term ended, his administration laid the foundation for further attacks on the press by Trump. The Biden administration continued the unprecedented Espionage Act prosecution against WikiLeaks founder Julian Assange, and in Florida, FBI agents raided the home newsroom of Timothy Burke in 2023. The following year, the DOJ charged Burke as an economic cybercriminal. (A jury trial is scheduled for September 8, 2025.)

Those guilty of journalism could have had the ability to go to court and fight back against Trump’s war on the press. But now, as Trump officials spread propaganda to demonize reporters and whip up public support for violating their First Amendment rights, there is little that the news media can do to stop petty and vindictive officials eager to target them and their sources.