Russia Matters, 3/14/25

- In the past month, Russian forces made a net gain of 110 square miles in Ukraine (about 1 Nantucket island), according to the March 12, 2025, issue of the Russia-Ukraine War Report Card. In addition, the Russian army appeared on March 14 to be close to driving Ukraine from all the territory it had seized in Russia’s Kursk region, according to NYT’s March 14 report. The elimination of this salient, which Vladimir Putin discussed during his surprise visit to the Kursk region on March 12, would deprive Volodymyr Zelenskyy of a major bargaining chip in direct negotiations with Moscow if and when they would occur. Based data from ISW, RM’s War Report Card of March 12, 2025 estimates that Ukraine controlled only 79 square miles of the 470 square miles it captured at the height of its Kursk incursion in Sept. 2024: an 83% drop.

- During their March 11 meeting in Saudi Arabia, high-level U.S. and Ukrainian delegations endorsed the West’s proposal for an immediate 30-day ceasefire in the Russian-Ukrainian conflict contingent on Russia’s consent to observe it. However, even before Steve Witkoff, a member of the U.S. delegation, could take the proposal for the unconditional ceasefire to Moscow, Vladimir Putin’s chief foreign policy aide Yuri Ushakov spoke against it. “This is nothing other than a temporary time-out for Ukrainian soldiers, nothing more. Our goal is a long-term peaceful resolution,” Ushakov said March 13. Speaking later that same day, Putin gave a qualified approval of the proposal, conditioning its adoption on a number of Russian demands. “We start from the position that this cessation should lead to a long-term peace and eliminate the causes of this crisis,” Putin said. “Then there arise questions over monitoring and verification,” said Putin prior to meeting Witkoff, whom he reportedly kept waiting for eight hours. In the absence of Russia’s unequivocal support for the ceasefire proposal, both Putin and Trump took pains to avoid admitting a setback. Trump described Witkoff’s meeting with Putin as productive. “There is a very good chance that this horrible, bloody war can finally come to an end,” Trump claimed. A decision on a phone call or a meeting between Trump and Putin will be made once Witkoff has relayed to Trump the information from the talks, according to Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. Witkoff flew from Moscow to Baku upon completing his visit to the Russian capital, with Trump reportedly expecting his aide back in the U.S. so that Trump can “learn more” about the outcome of the talks with Putin on March 17.

- In addition to Witkoff’s visit to the Russian capital, several more government-to-government contacts have been reported between America and Russia this week as Moscow and Washington continue to explore normalizing the bilateral relationship. The head of Russia’s Foreign Intelligence Service, Sergei Naryshkin, and U.S. CIA Director John Ratcliffe agreed to maintain regular contacts during a phone call March 11 to discuss cooperation between their agencies, according to Bloomberg. Meanwhile, Russian and European officials say the U.S. is exploring ways to work with Russia’s energy giant Gazprom on global projects, according to Bloomberg. It has also been earlier reported that U.S. and Russian officials are already discussing issues ranging from the resumption of direct flights and the return of Russian diplomats’ missions in the U.S., to Russian-Ukrainian peace and Russian assistance to the U.S. in communicating with Iran over its nuclear program. Moreover, the Kremlin is exploring its options for a potential meeting between Putin and Trump in April or May in the Middle East, Russian officials told MT.

***

Negotiation Dance Between Trump & Putin

By Jeff Childers, Substack, 3/15/25

Yesterday, we looked at the public negotiation dance playing out between President Trump and President Putin. A new song has begun to play. Reuters ran an encouraging story yesterday afternoon headlined, “After Trump request, Putin says he will let Ukraine troops in Kursk live if they surrender.”

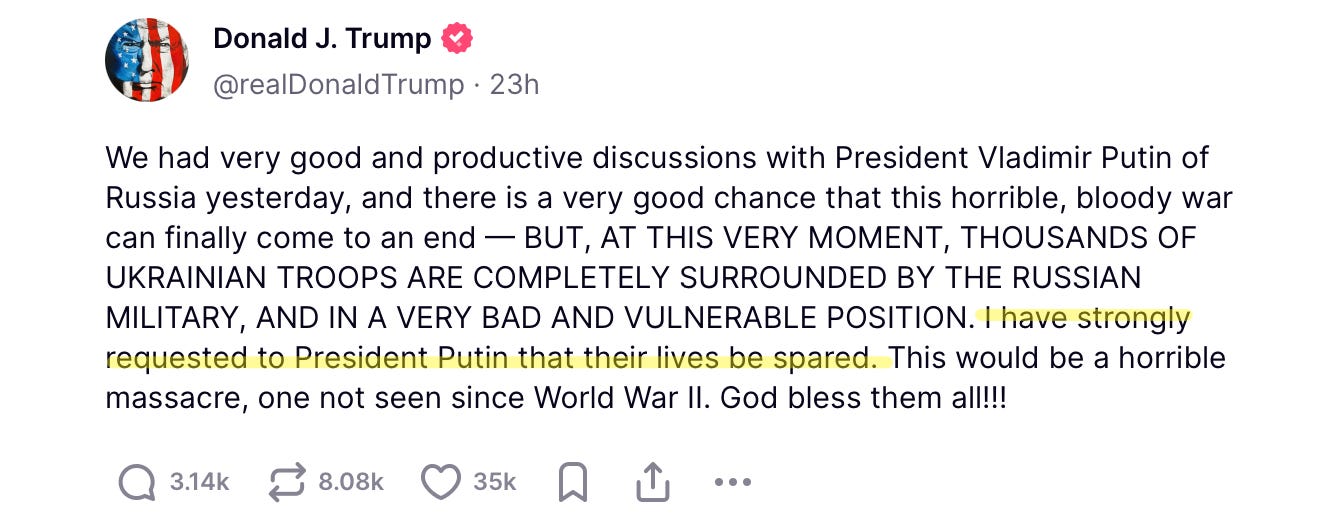

Appropriately (and surreally), it all started yesterday with a Trump tweet on Truth Social, requesting that President Putin spare the lives of Ukrainian troops surrounded in the doomed Kursk salient:

Later in the day, President Putin addressed his Security Council saying he’d read Trump’s appeal. “In this regard, I would like to emphasize that if [Ukrainian troops] lay down their arms and surrender, they will be guaranteed life and decent treatment under international law and the laws of the Russian Federation,” Putin informed his team in a part of the meeting that was publicly broadcast.

Tellingly, President Putin stressed the new policy was in response to Trump’s ask: “To effectively implement the appeal of the US president, a corresponding order from the military-political leadership of Ukraine is needed for its military units to lay down their arms and surrender.”

Bizarrely, Ukraine defiantly insisted its Kursk troops are not surrounded, so there is no reason to surrender. Media reported those crazy claims without criticism, but also without enthusiasm. Nobody seems to believe Zelensky.

As usual, witless corporate media completely missed the mark, clueless to the fact that Putin’s concession shows progress in the delicate peace negotiations. Most media framed the story as Putin’s “demand for Ukraine to surrender.” For example, here’s the Seattle Times’ take:

Media couldn’t see an elephant if it were sitting in the passenger seat. Here’s the actual timeline: yesterday, Putin graciously reviewed the US’s proposed cease-fire, and responded with a bunch of correct but complicating questions, including what happens to the surrounded Ukrainian troops in Kursk? Can they just walk away?

Trump indirectly responded to that question with his tweet. It coyly avoided actually asking for anything, but rather suggested Russia should spare their lives. And Putin, citing Trump’s request, agreed. He promised that if the Ukrainians lay down arms and surrender, he will guarantee their safety. It is a huge improvement —right now, they face imminent death— and more importantly, it resolved one of Putin’s most important questions about the proposed cease-fire’s terms.

🚀 President Trump masterfully deployed a well-known negotiating technique called incremental agreement. Rather than trying to get your adversary to agree to a large, complicated deal, you start by peeling off the easiest issues one-by-one. After your negotiating partner starts saying ‘yes,’ or ‘da,’ each subsequent incremental agreement becomes that much easier, and before you know it, Bob’s your uncle and you have a final deal.

It was a win for both parties. Putin handed Trump a highly visible incremental agreement that went to the heart of Trump’s stated goal: to stop the killing. For his part, Putin garnered points for being reasonable and for visibly working toward a deal—which blows the media’s stonewalling narrative to bits. And the Russian president skillfully jammed the Ukrainians into a painful crack: if they refuse to agree and lay down arms, he’ll then be fully justified in wiping them out.

And then the Americans can blame Kiev, for Zelensky’s stubborn intransigence.

That explains why the Ukrainians are pretending their troops are not surrounded. That unbelievable claim is the only remaining safe spot to hide in. Of course, everyone realizes they should order the troops to put down their weapons, rather than letting the Russians turn them into battlefield chum. But the Kiev regime has long showed a strategic choice of never surrendering. It’s the last thing they want to do.

And very soon now, somebody is going to ask Zelensky the obvious question, why not just order any surrounded troops to surrender? If no troops are surrounded, then asking them to surrender wouldn’t matter, would it?

See what just happened? Trump meaningfully convinced Putin to change Russian military policy—on Twitter. (I know, Truth Social.) Meanwhile, Ukraine’s government is reduced to incredulously denying the battlefield even exists. The game of peace-deal hide-and-go-seek is moving fast, and Zelensky is running out of hiding places. They’ve already chucked the dimunitive former comedian out of the negotiating room. Very soon, the inevitable and only question will be: does Ukraine want peace or not?