(American Progress, an 1872 painting by John Gast, is an allegorical representation of the modernization of the new west. Here Columbia, a personification of the United States, leads civilization westward with American settlers; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Manifest_destiny)

The Greater Good project at UC Berkeley recently published an article, The Science of the Story which discusses the science behind storytelling – how it affects humans on a biological level and its implications, both for forging empathy and for potentially exerting control. The article states:

Experiencing a story alters our neurochemical processes, and stories are a powerful force in shaping human behavior. In this way, stories are not just instruments of connection and entertainment but also of control.

This article naturally interested me as a fiction writer; but it interested me just as much as an analyst on Russia and U.S. foreign policy. In terms of the stories we tell about the other and how that shapes policy and vice versa, potentially leading to a vicious circle with terrible ramifications, understanding the consequences of the narrative is critical. My attempts, via articles and blog posts, to provide facts and information about Russia to counter the distortions we constantly hear from our politicians and media that paint that country in a bleak and ominous manner are an important part of that.

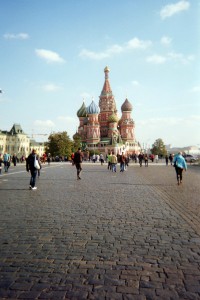

However, just as important as the story we tell about Russia (or any other country) is the story we tell about ourselves. As Stephen Kinzer discussed in the presentation I posted a few days ago, there has been a strong strain within our culture from its earliest days to view America as a shining city on a hill with a special God-given mission to remake the world in our image. In the 19th century it was known as Manifest Destiny, in the 20th century we represented the Free World against the “Evil Empire” during the Cold War, and today it is Exceptionalism with a mission of spreading democracy and a “Responsibility to Protect.”

As David S. Foglesong, an historian at Rutgers University, points out in his 2007 book The American Mission and the “Evil Empire,” this self-righteous impulse to convert or reform in relation to Russia has existed to varying degrees since the late 19th century:

There was something about Russia that made it more persistently fascinating. Since Russia could be seen as both like and unlike America – both Christian and heathen, European and Asiatic, white and dark – gazing at Russia involved the strange fascination of looking into a skewed mirror. The commonalities, such as youth, vast territory and frontier expansion that made Russia seem akin to the United States for much of the 19th century served to make Russia especially fitted for the role of “imaginary twin” or “dark double” that it assumed after the 1880’s and continued to play through the 20th century. Soviet communism, as an atheist and universalist ideology, came to seem, more than any other rival creed, the antithesis of the American spirit. Thus, more enduringly than any other country, Russia came to be seen as both an object of the American mission and the opposite of American virtues. (page 6)

This dynamic of fascination and revulsion and the role of “dark double” are reminiscent of what Carl Jung referred to as the “shadow” – that part of one’s self that one doesn’t like and doesn’t even wish to acknowledge. This denial inevitably leads to pathology in the individual.

Something similar can be seen in the earliest days of America’s messianic attitude toward Russia (and others) as Foglesong highlights how the height of the sanctimonious condemnations against the alleged sins of Tsarist Russia in the late 19th century coincided with the rise of domestic problems in America, which showed that all was far from perfect up on the hill. These included:

…declining religious faith, demoralizing materialism, dishonorable treatment of Native Americans, and the disenfranchisement and lynching of African-Americans. Discomfort with such troubles inclined journalists, editors, ministers, and other opinion leaders to emphasize problems in Russia that made American imperfections pale in comparison. Thus as Americans resolved uncertainties and conflicting notions about Russia, that country gradually came to serve as a “dark double” or “imaginary twin” for the United States….Treating Russia as both a whipping boy and a potential beneficiary of American philanthropy fostered in many Americans a heady sense of their country’s unique blessings, and reaffirmed their special role in the world. (pages 11-12)

This superior self-image and messianic tendency is rooted in the Puritan/Calvinist strain of Protestantism of the early European settlers. Foglesong also documents that the journalists and activists who were most responsible for portraying Russia in the late 19th and early 20th century as unusually brutal, backward and repressive and consequently stirring up public opinion against the Tsarist government, had religious backgrounds.

A prime example is George Kennan, a journalist who actually began his career as a skeptic of Russia’s revolutionary movement. But a sequence of events while on assignment investigating Russia’s exile system for Century magazine in 1884-85 resulted in a conversion of sorts. Kennan had a religious upbringing but became disillusioned in terms of trying to reconcile his faith with science and his observations during his travels as a journalist. After meetings with some of the revolutionaries, he began to sympathize with what he saw as their sophisticated western-style intellectualism. This sympathy deepened after he got sick in the borderlands between Russia and Mongolia and he encountered Russian exiles whose courage and endurance inspired him.

Kennan soon took up the revolutionaries’ cause against the “evil” Tsarist government. In his zeal, however, Kennan became less objective in his reporting and often disseminated embellished or even fabricated events and characterizations of the conditions in Russia, portraying the Tsarist government in the most simplistic and blackest terms.

As biographer Frederick Travis has shown, Kennan exaggerated conditions and invented episodes in order to paint Siberian prisons “in even blacker colors than the shade that some of them so richly deserved.” Only a few years earlier Kennan had maintained that the exile system was no worse than western prisons, but now he rejected such comparisons and insisted upon absolutist moral condemnation of tsarist brutality. (page 17)

Kennan also misrepresented how America was viewed by Russians, particularly Russian political dissidents who had largely been disabused of their idealistic notions of America and its capitalist system after visiting here in the 1870’s, subsequently exploring socialism as an alternative foundation for reform or revolution. Foglesong also makes the point that Kennan and other crusaders for a “free Russia” showed little interest in what the majority of Russians actually thought about the prospect of being “saved” by these self-appointed forces of light, a glaring omission in the American discourse.

The similarities of these early writers and their agenda to the dynamics of the secular missionary writers of today, like Masha Gessen, Edward Lucas and Anne Applebaum, with their never-ending depictions of contemporary Russia as a nightmarish cesspit lorded over by a demonic Putin, who is preventing the Russian masses from realizing their profound desire to become Americans in furry hats, is striking.

Of course, a narrative in which one necessarily represents a paragon of goodness requires an evil other as a contrast to continually demonstrate that goodness. And when one’s self-image is that of the righteous against an evil foe, it then justifies virtually any means to convert or vanquish the evil – coups, assassinations, massive bombing campaigns (“we had to destroy the village in order to save it”), perhaps even a nuclear first strike as some of president Kennedy’s military advisers had recommended in the early 1960’s – a possibility that some in Washington apparently have not taken off the table. The recent installation of a missile shield in Romania aimed at undermining Russia’s capability for a retaliatory nuclear strike, despite Washington’s implausible denials, only feeds into this dangerous notion.

Even the 19th century advocates of Manifest Destiny in all its expansionist flavors had their ideological opponents, those who challenged the notion that American righteousness was a self-evident truth and that it justified imposing its way on other parts of the world. Instead, they argued that the wisest path was for America to focus on solving its own problems, being the best country it could be and to, hence, serve as an example to others.

The story of being exceptional, with the implication that others are less and in need of reform, conversion or even destruction if they refuse American demands to figuratively “come to Jesus”, is a dangerous one. Where are those today who can offer a valuable alternative narrative that is needed more than ever in a nuclear-armed world?