Order book here: https://www.amazon.com/Sofia-Perovskaya-Terrorist-Princess-Alexander/dp/0999155911

Over the President’s Day weekend, I attended my first San Francisco Writer’s Conference. During a short break on the second day, I perused the area where tables were set up in which vendors offered their services and some attending authors had their published books for sale.

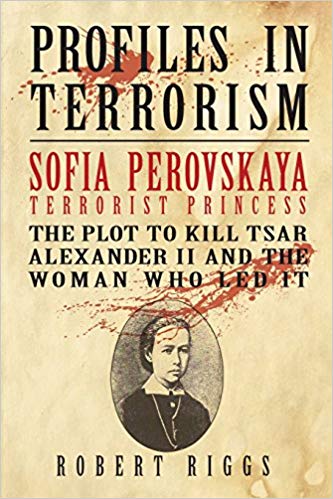

Imagine my delight when I came across this book by fellow attendee Robert Riggs – especially since I’d just been working on the chapter of my own book involving Alexander II. I immediately plunked down my $20 and started reading it later that night in my room and finished it within a couple of days. I later encountered the author at a session for non-fiction writers. He signed my book and we had a short but interesting discussion on historical Russia.

This is actually the first published book in a series Riggs is doing on what terrorists have in common in terms of personality and background, so the emphasis is on how Sofia Perovskaya – who masterminded the assassination of the reformist tsar – fits a profile of a long list of terrorists. Future books planned for the series will cover other perpetrators of political violence such as John Brown, John Wilkes Booth, as well as more recent individuals.

Based upon the studies of Walter Lacquer, Riggs reiterates that terrorism is not a product of poverty, injustice or any particular religion, ethnicity, etc. Furthermore, terrorists themselves do not typically come from the aggrieved groups on whose behalf they claim to be acting. From the introduction, Riggs writes:

By no means poor and oppressed beings, they are generally children of wealth and privilege who go overboard in adopting the cause of others….There is an identifiable constellation of personality traits, what we call here a profile, that is strongly associated with persons who act out as terrorists, regardless of the particular cause or value structure that the terrorist happens to be supporting….Unfortunately, we see that under certain conditions terrorists can “grow” other terrorists by exploiting, cultivating and bringing out its inherent personality attributes, especially among young people. (pp. iii – iv).

While I certainly found this thesis fascinating, I was very interested in the historical background provided by Riggs of Russia during the 1860’s and 1870’s, including the revolutionary philosophy that was influential during this time.

Riggs gives a detailed outline of the 1863 novel What is to Be Done? by Nikolai Chernyshevsky, which captured the imagination of a segment of restless young revolutionaries. The book illustrated the ideals of a utopian future filled with socialist coops and equality between the sexes. However, it also was interpreted as having oblique references to the necessity of destruction and even suicide to achieve the utopian goal.

The novel greatly influenced other writers and revolutionary thinkers, including Mikhail Bakhunin, who in turn, influenced a segment of frustrated reformers and activists such as Perovskaya, a veteran of the largely unsuccessful “peasant movement” that was aimed at raising the consciousness of peasants toward rebellion.

Bakhunin and his fellow travelers preached the “necessity of violence for suppressing the privileged classes.” There was no more patience for gradual reforms, consciousness-raising, or non-violent forms of direct action such as strikes, blockades, etc.

Bakhunin eventually teamed up with Sergey Nechaev in Switzerland. Nechaev was known for being manipulative and stridently intolerant of those with differing viewpoints. He had fled Russia after engaging in violent activities that had earned him attention from the authorities, including the murder of an early follower who had turned against him.

Together, they wrote Catechism of a Revolutionary which outlined the requirements for revolutionaries to be successful. The requirements included: the forsaking of all other interests and attachments for the revolutionary project; the suppression of empathy and engagement in anti-social activity on behalf of opposing all established civil order, institutions, customs and morality; the only criteria for determining morality was whether something advanced the revolutionary project or not; the ends justified the means; willingness to die and endure pain for the revolutionary project; and, in the service of expediting the revolution, it was permitted for conditions to actively be worsened for the future beneficiaries of the revolution. (pp. 95-98)

Within the original organization that Perovskaya had been active in, a split emerged between those who advocated terrorism and those who preferred other direct actions along with the continued education and propagandizing of workers and peasants.

Perovskaya and her supporters ultimately decided to focus solely on assassinating the tsar. They made several failed attempts that involved the tunneling of areas beneath routes Alexander was supposed to take in his travels around St. Petersburg.

They finally achieved their goal on March 1, 1881 with a series of assassins stationed at intervals on the tsar’s route, each armed with a homemade bomb to toss at the imperial carriage.

Ironically, word had gotten out shortly before that Alexander had decided on another round of reforms which would have laid the groundwork for a constitution. Some of Perovskaya’s colleagues had voiced misgivings at this point about continuing to pursue regicide, suggesting the possibility of giving the reforms a chance.

But Perovskaya’s mind was made up and enough of her colleagues agreed to participate in the plan.

After the assassination, police were able to get some of the revolutionaries to turn on others. This, along with surveillance and a sharp investigator, eventually led to the capture of all the perpetrators. After a sensationalist trial, they were all publicly hanged.

Although I approached this book primarily with an interest in Russian history of the period, I also found the psychological portrait of Perovskaya and her partners in crime to be compelling.

Natylie! Thank you so much for that. A book I would probably not have encountered otherwise. The whole topic of 19th century utopian idealism leading to violent revolutionary behaviors is so inadequately documented and, indeed, fraught with such contradictions, that one would not necessarily even know to find a book such as this. Many Thanks! Eagerly awaiting yours, as well, even if that’s not so much what it is about.

Thanks Dan! Before I picked up this book, I was primarily relying on 1 book on Russian philosophy and 3 comprehensive history books of Imperial Russia – two of which included a fairly in-depth discussion of revolutionary thought in 19th and early 20th century Russia. But these sources were all rather dry. This one explained a portion of that thought in a more accessible way, which was helpful in my distillation of the subject for my own book.

I’m now looking at an early Summer release date for my book. There’s so much to do when you self-publish. But it will still get out faster than if I had a traditional publisher which typically takes 18 months to 2 years to get a book out after the manuscript has been completed. I still have a couple of chapters to write before the first draft of my manuscript is done. I’ll be offering some more sneak peeks along the way on this blog. Stay tuned!