The Bell, 8/30/24

Russia’s mid-term future: high interest rates and high inflation

Russia’s Central Bank published Thursday a document laying out its vision for the economy over the coming three years. Titled the “Main Directions of Monetary Policy 2025-27,” it examines four different scenarios (the worst of which would see Russia plunge into a deeper crisis than 2008). Taken together, the scenarios appear to confirm that Russia will continue to increase spending on the war in Ukraine, and that the country is likely to face persistent high inflation and several years of double-digit interest rates.

Four scenarios

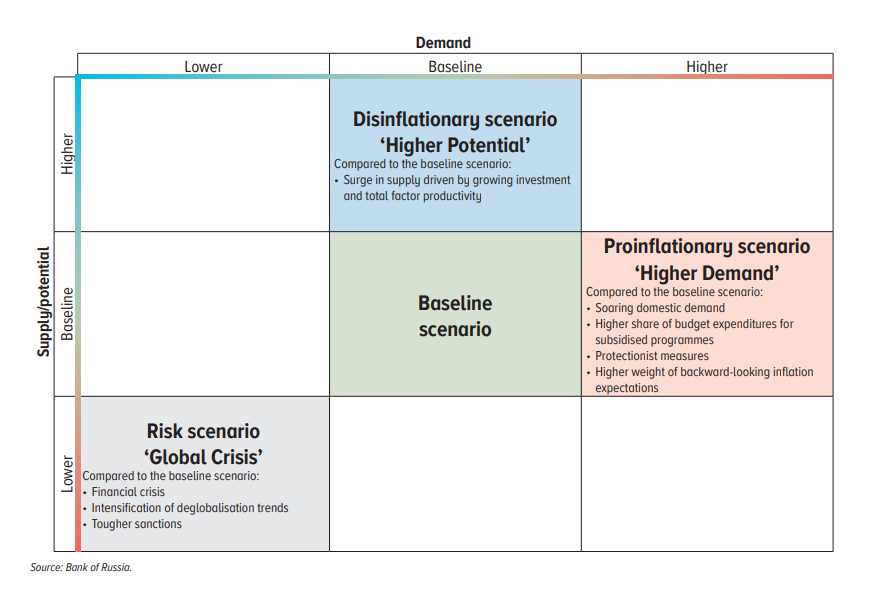

This is an annual report, and the Central Bank always reviews several different scenarios for economic development. Last year, there were three such scenarios, this time (“due to complex internal and external circumstances”) there were four: one baseline, two pessimistic (persistent inflation and high-inflation) and one optimistic (low-inflation).

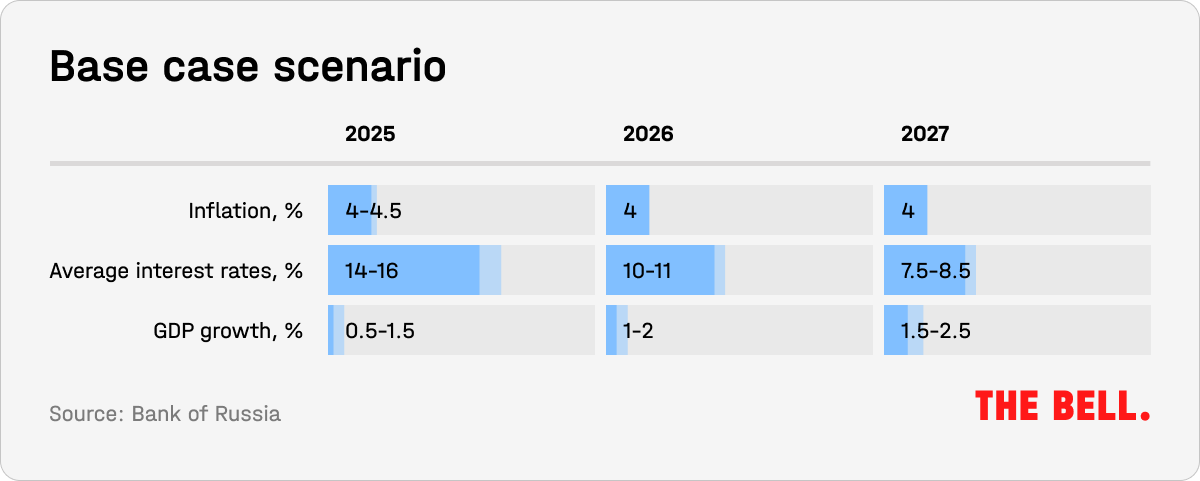

The bank’s baseline scenario assumes that inflation will slow to 4-4.5% next year, and will continue to hover around 4% in the longer term. To achieve this, monetary policy will remain tight. GDP would grow by 3.5-4% in 2024, before slowing in 2025 and 2026.

The baseline scenario is the one considered most plausible. However, one of the biggest variables is the level of state spending and state subsidies in the coming years, Central Bank deputy chairman Aleksei Zabotkin told journalists at a press conference.

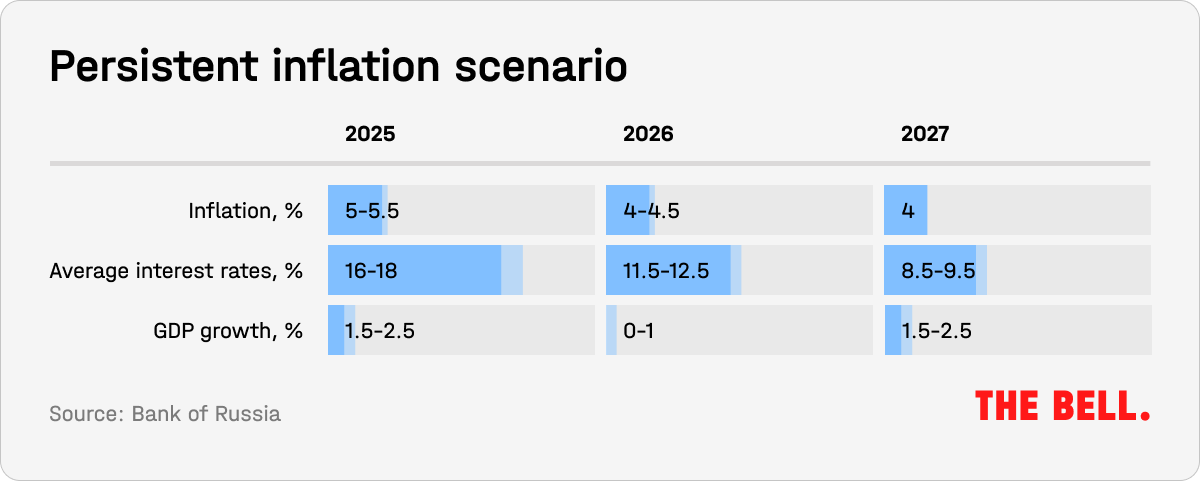

Both pessimistic scenarios (persistent inflation and high-inflation) assume that interest rates will remain in double digits. In the persistent inflation scenario, the labor market would remain tight and inflation would be driven by high domestic demand (which, in turn, would be supported by state spending), as well as increased wages. In this scenario, average interest rates would have to stay one or two percentage points higher than in the baseline. But even under such tight monetary conditions, inflation was not predicted to fall to 4-4.5% until 2026.

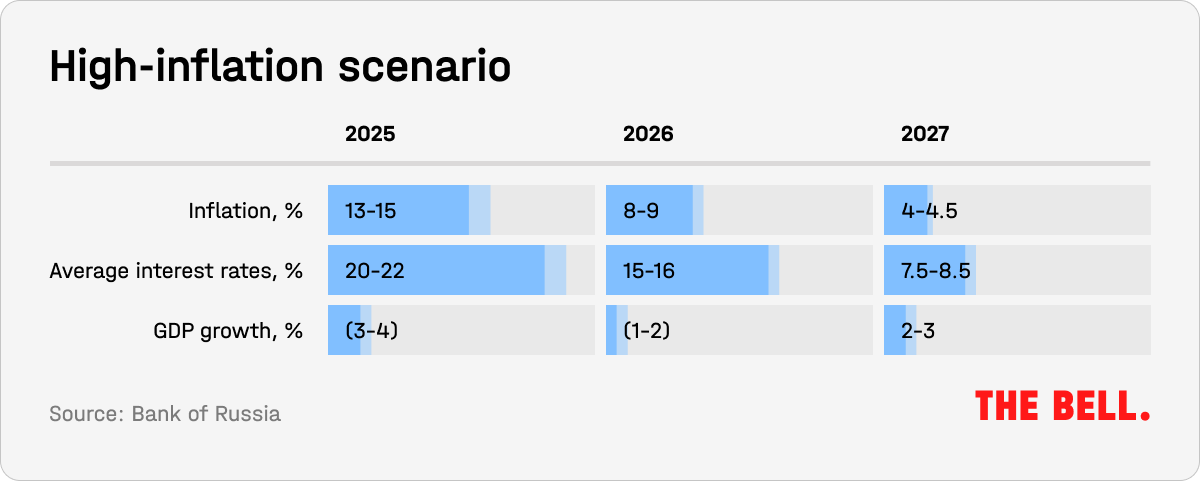

The high-inflation scenario is even more dire. In this eventuality, the problems in the Russian economy are amplified by a serious deterioration in external circumstances: disbalance on the financial markets leading to a global financial crisis and recession. While the Russian economy is internationally isolated, falling demand for Russian products was still assumed to cause significant damage. This scenario also envisaged more Western sanctions on Russia. If this comes to pass, the prediction is that the Russian economy would enter recession, inflation hit 13-15% and interest rates soar to 22%.

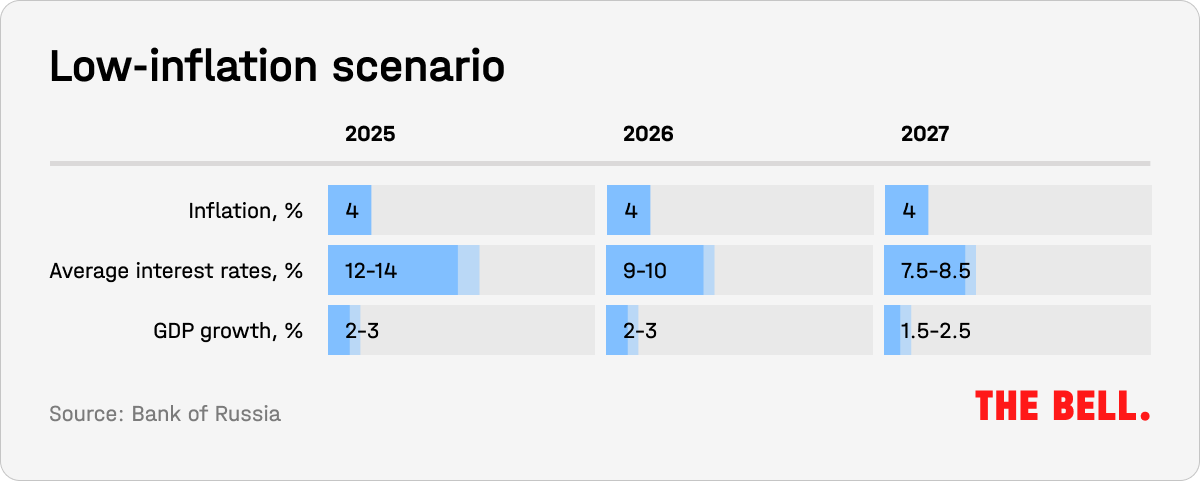

There is also an optimistic scenario – low-inflation. This assumes significant increases in investment, and growth in productivity. In this case, inflation would fall faster than in the baseline scenario, economic potential would increase, and GDP would rise.

However, with the Kremlin’s current economic policies and existing structural restrictions, the chances of this scenario occurring are not great.

Inflation is here to stay

Under current circumstances the persistent inflation scenario is the most likely of the four. It assumes that the high demand we witnessed in the second half of 2023 will be sustainable, and will continue through 2025. In other words, the state will maintain high levels of spending in order to fund the war in Ukraine.

The persistent inflation model also assumes stronger protectionist policies, as well as the imposition of import tariffs to stimulate import substitution. Winegrowers and winemakers, domestic electronics assemblers, polymer and plastic processors, manufactures of Russian trucks and automobiles and many other sectors are already urging the government to impose import tariffs. Of course, any new foreign trade tariffs are, by definition, pro-inflationary. They make imported goods more expensive and push up demand for domestic goods, which translates to increased prices.

However, government spending is the biggest inflation driver. The Central Bank estimates that the cost of fulfilling all of the goals set by President Vladimir Putin in this year’s state-of-the-nation address will be 18 trillion rubles ($199 billion) between now and 2030. This includes new social spending, loan write-offs, tax breaks and more. In its reports, the Central Bank highlighted Putin’s promises to increase the minimum wage by an annual average of 10.5% through 2023; index pensions at 8.8-14.7% every year; resume indexed pensions for working pensioners from 2025; and increase payments for children. In addition, Putin announced major spending on road building, housing and communal services. Of course, the government can always postpone these spending plans, and use alternative sources of income to fund its war (read more about this here).

State spending has a huge impact on demand and inflation, according to the Central Bank. It results in organizations and the public demanding more credit to expand production and consumption, including real estate purchases – and increases in interest rates are unable to fully keep pace with these pro-inflationary factors. Moreover, in this scenario, businesses and households will focus more on past cases of high inflation when making purchasing decisions, which risks fixing inflationary expectations at a higher level.

The Central Bank has already alerted the Kremlin to the risk of increasing inflation. At a meeting on Aug. 26, Putin urged the government to assist the bank in curbing rising prices, Vedomosti reported. The discussion focused on measures to reduce subsidized lending.

Why the world should care

The most likely economic scenario for Russia’s economy over the next three years appears to be one of accelerating inflation and high interest rates. The Central Bank’s latest three-year forecasts assume increases in state spending (far outstripping what will be collected via higher taxes). This would be yet another major boost to inflation.

EU imports to Russia in June hit lowest monthly level for 20 years

The volume of imports from the European Union to Russia in June reached its lowest level for more than 20 years, according to Eurostat figures. Total exports from the EU to Russia in June were worth €2.472 billion – the lowest figure since Jan. 2003.

- The main reasons for the ongoing collapse in these figures are EU sanctions and the threat of secondary U.S. sanctions, plus the voluntary withdrawal of European companies from trade with Russia since its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

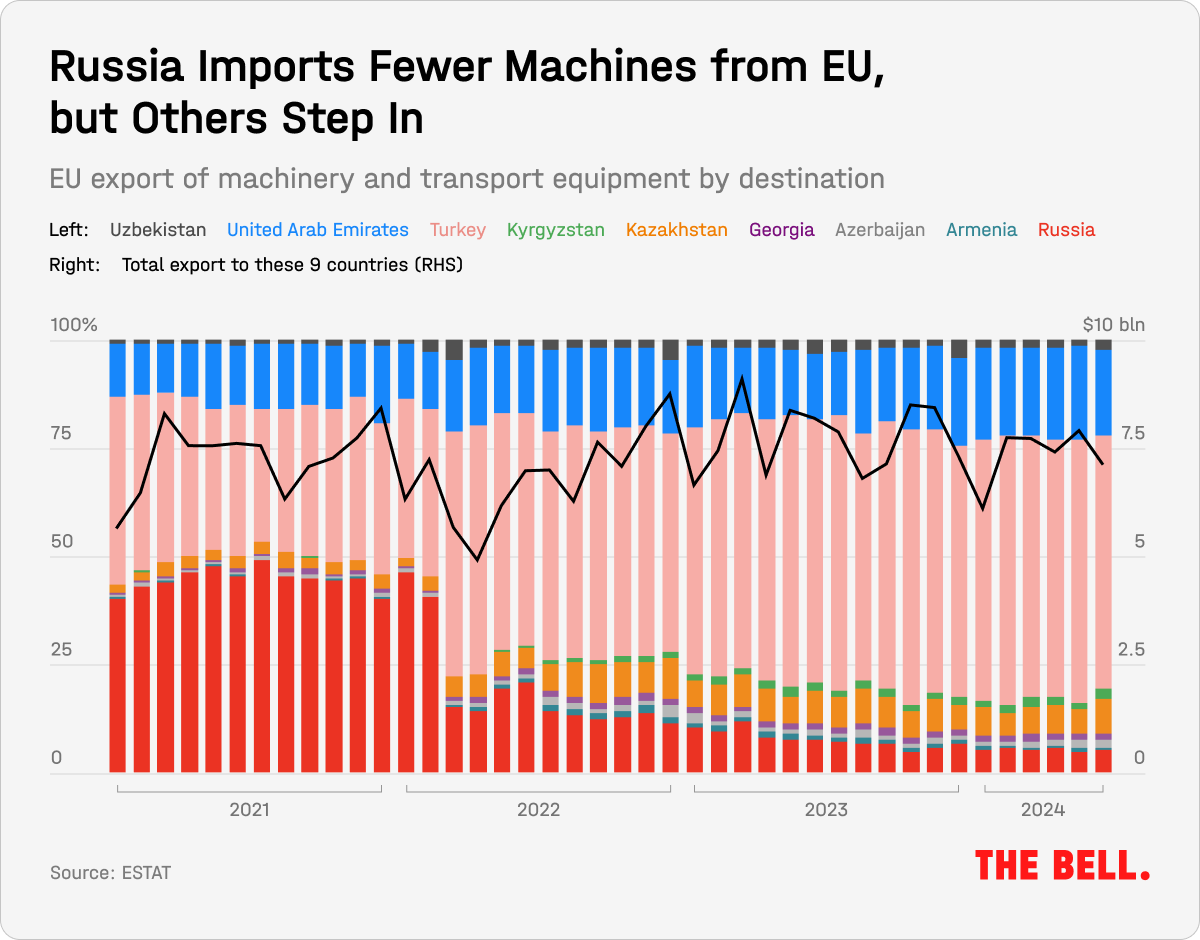

- The decline is visible in all sectors—from automobiles and alcohol to microchips and machine tools. However, the same Eurostat data indicates that Russia is meeting its need for European goods with the help of “friendly” nations.

- This is illustrated by one of Russia’s key defense sectors: machinery and transport. Here, the drop in European exports to Russia has been matched by a sudden increase in exports to some ex-Soviet nations, the UAE, and Turkey. This growth cannot be explained by surging demand in those countries and strongly suggests that the buyers are simply re-exporting EU goods to Russia.

- Evidence of re-export is also visible in microchips (the EU has almost completely banned microchip exports to Russia). Direct trade in these crucial parts between the EU and Russia plummeted from being worth €56 million in June 2021 to just €2,500 in June 2024. However, at the same time, Russia’s neighbours actively started importing microchips from Europe: for example, Turkey bought €14 million worth in June 2021 and €24 million worth in June 2024. The growth is even more steep in countries like Armenia in the South Caucasus and Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia, although the volumes are smaller.

- This can also be seen in the market for ship propellers and blades. Before the war, Russia imported €2.5 billion worth a year of these products. Now, they are classed as dual-usage goods and cannot be delivered directly. However, countries like Turkey, the UAE and even landlocked states such as Armenia and Kyrgyzstan have significantly increased their orders of European propellers.

- It’s difficult to gauge China’s role in re-exporting to Russia from these statistics as the volumes are too big to pick out tell-tale anomalies. Nevertheless, many believe that Beijing is the biggest re-exporter of EU goods to Russia.

- Western countries have long been concerned about the re-export of sanctioned goods to Russia, especially dual-use goods. The recent 14th package of EU sanctions addresses the issue by requiring exporters to check the final purchaser. The U.S. also threatens to impose secondary sanctions in case of re-exporting the sanctioned goods. The effect of these measures will take some time to materialise in full.

Why the world should care

It’s unlikely that the recent anti-circumvention measures will completely stop or greatly reduce re-exports to Russia. However, the more barriers are put in place, the more expensive it will be for Russian companies to obtain the Western goods they require. This pushes up inflation inside Russia and limits productivity.

Figures of the week

Inflation is falling. Between Aug. 20 and Aug. 26, weekly inflation was 0.03% (last week, it was 0.04%), according to the Economic Development Ministry. Annual inflation slowed from 9.04% to 9.01%. Despite the seasonal fall in fruit and vegetable prices, food prices continue to rise. Only regulated prices, as well as the costs of household and tourist services, are falling.

In the first half of this year, state-owned gas giant Gazprom increased its net profits 3.5 times year on year to 1.04 trillion rubles, according to the company’s financial statement. The growth is primarily due to increased gas exports following last year’s catastrophic fall, plus rising oil exports. In the first six months of 2024, gas exports to the EU were up by a quarter, from 14.8 billion cubic meters to 18.3 billion cubic meters. Over 2024 as a whole, Gazprom expects deliveries to China to increase by a third, from 22.7 billion cubic meters to 30 billion cubic meters, rising to 38 billion cubic meters next year. However, the price of selling gas to China is lower than to Europe, and exports are limited because there is only a single pipeline connecting the two countries. For the moment, the Chinese market is not enough for Gazprom to replace the losses it has suffered from the war and Western sanctions.

After a slight slowdown in June, industrial output in July returned to growth, according to Russia’s State Statistics Service. The industrial production index was up 3.3% in July, driven by the manufacturing sector. The four sectors with the biggest growth are all related to the war in Ukraine: computers and optics, finished metal products, medicine and healthcare, and transport.